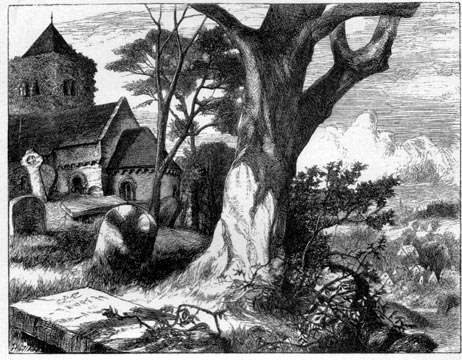

This is an excerpt from Chapter II ("Round about Hastings") of Louis Jennings' Field Paths and Green Lane (1878), the first of the popular books that Jennings wrote on returning to England after his time as editor of the New York Times (full details are given at the end). Jennings was a sympathetic recorder of country life, in the style of George Borrow (1803-1881). As David Morphet writes, here he "left his combative journalism well behind and revealed a side of his nature that his friends and acquaintances in public life did not always detect." Morphet then quotes Sir Henry Lucy, "the doyen of Victorian Parliamentary commentators," on his pleasure in detecting the sunnier side of Jennings' nature in these works (137). But what is on view in this particular extract, about an encounter in the churchyard of St Andrew, Fairlight, in East Sussex, is his more contemplative side. In editing it for the Victorian Web, I have included numbers in brackets to indicate page breaks in the print edition. This is to allow readers to cite or locate the pages in the original text. The illustration is The Churchyard of the Village, by W. P. Burton. [Click on the image to enlarge it, and for more information.] — Jacqueline Banerjee

A beautifully situated churchyard is this of Fairlight, and people have come from far and near, looking forward from "this bank and shoal of time" to choose a spot therein for their long home. Although a somewhat out-of-the-way country churchyard, there are many costly monuments in it, and several of them can boast of true beauty in their design. I found the old sexton at the second cottage beyond the church — a very old man wearing one of those frocks with much needlework at the top, back and front, which are now suggestive of bye-gone days. He was of a singularly mild and gentle aspect, and although his face was much wrinkled, it was almost good-looking by reason of his clear grey eye and honest smile. If this is not a good and worthy man, one thinks in looking at him, then for once has Nature hung out the wrong sign upon her work, which she rarely does.

"You have some grand monuments here," said I, when we had got into the churchyard. [26/27]

"Yes, sir, there are many rich folks have been brought here, and we were obliged to take that piece into the churchyard" (pointing to the east side of the ground). "Our church was rebuilt some years ago, but there be a many old graves in it. There is a stone here which they do say is two hundred years old."

"And so strangers come to you as well as your own people?"

"Oh, yes. You see that white marble cross? Well, that, and the two graves next to it, were chosen by a gentleman from India, as you see his name writ up, and he had his brother brought here after he had been buried a many years in London. Then he had some others of his family brought here too. And now you see, sir, how things go in this world. This gentleman was dressing himself one morning, quite well as you might be, and five minutes after he was dead. And there he is.

"Oh, yes, we've had a sight of people buried here, and money spent on the graves. Thousands of bricks have been put in the vaults. Some people like to do that, and it makes work, that's all. You see that grave over yonder, sir? The lady as is there was buried fourteen year, and when we opened it to put the gentleman in, the lid and handles of the coffin were as bright as they were on the day they were made. It was a brick grave, and better nor any vault, for we are very dry up here. It's the wet as breaks folks up, sir.

"A year and a half ago I buried my poor missis over there" (pointing to the south-west corner of the church- [27/28] yard). "I have felt lonesome like ever since, although my daughter came to me after her mother died."

We were standing within the porch of the church, the old man bareheaded, and there was that in his face and words which made one silent.

"One day a big boy was trying to prevent some little children going home, just by that gate, and she interfered to protect them. The boy up with his fist and struck her on the breast. She was very ill afterwards, and got very thin, and we took her to the doctors, but it was all no use, sir."

"A cancer, I fear?"

"I think that was the name of it, sir. Poor thing! it was only fourteen months afore she came to the ground."

"How old are you ?" I asked presently.

"If I live till next month, sir, I shall be seventy-five years, and twenty-four years I have lived here. Yes, sir, it is a lonely place in winter, bein' out of the way like, but I have neighbours, and my daughter lives with me since her mother died."

The old man came and opened the gate for me, and as I walked home there lingered the recollection of his old-fashioned ways, his quaint speech, and the simple pathos of the phrase in which he told of his wife's death : "She came to the ground." With how sharp a stroke it lays bare to the mind the end of this poor little drama in which most of us are playing our parts so ill.

Sources

Jennings, Louis. Field Paths and Green Lanes: being Country Walks, Chiefly in Surrey and Sussex. 2nd ed. London: John Murray, 1878. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of California Library. Web. 8 February 2016.

Morphet, David. Louis Jennings MP, Editor of the New York Times and Tory Democrat. London: Notion, 2001.

Created 13 February 2016