This essay, which first appeared in Harper's Weekly, has been adapted from the Project Gutenberg [EBook #25767] of Picture and Text (pp. 44-60), which Harper Brothers published in 1893. David Widger produced the electronic version. — George P. Landow.

Nothing is more interesting in the history of an artistic talent than the moment at which its "elective affinity" declares itself, and the interest is great in proportion as the declaration is unmistakable. I mean by the elective affinity of a talent its climate and period of preference, the spot on the globe or in the annals of mankind to which it most fondly attaches itself, to which it reverts incorrigibly, round which it revolves with a curiosity that is insatiable, from which in short it draws its strongest inspiration. A man may personally inhabit a certain place at a certain time, but in imagination he may be a perpetual absentee, and to a degree worse than the worst Irish landlord, separating himself from his legal inheritance not only by mountains and seas, but by centuries as well. When he is a man of genius these perverse predilections become fruitful and constitute a new and independent life, and they are indeed to a certain extent the sign and concomitant of genius. I do not mean by this that high ability would always rather have been born in another country and another age, but certainly it likes to choose, it seldom fails to react against imposed conditions. If it accepts them it does so because it likes them for themselves; and if they fail to commend themselves it rarely scruples to fly away in search of others. We have witnessed this flight in many a case; I admit that if we have sometimes applauded it we have felt at other moments that the discontented, undomiciled spirit had better have stayed at home.

Mr. Abbey has gone afield, and there could be no better instance of a successful fugitive and a genuine affinity, no more interesting example of selection—selection of field and subject—operating by that insight which has the precocity and certainty of an instinct. The domicile of Mr. Abbey's genius is the England of the eighteenth century; I should add that the palace of art which he has erected there commands—from the rear, as it were—various charming glimpses of the preceding age. The finest work he has yet done is in his admirable illustrations, in Harper's Magazine, to "She Stoops to Conquer," but the promise that he would one day do it was given some years ago in his delightful volume of designs to accompany Herrick's poems; to which we may add, as supplementary evidence, his drawings for Mr. William Black's novel of Judith Shakespeare.

Mr. Abbey was born in Philadelphia in 1852, and manifesting his brilliant but un-encouraged aptitudes at a very early age, came in 1872 to New York to draw for Harper's WEEKLY. Other views than this, if I have been correctly Informed, had been entertained for his future—a fact that provokes a smile now that his manifest destiny has been, or is in course of being, so very neatly accomplished. The spirit of modern aesthetics did not, at any rate, as I understand the matter, smile upon his cradle, and the circumstance only increases the interest of his having had from the earliest moment the clearest artistic vision.

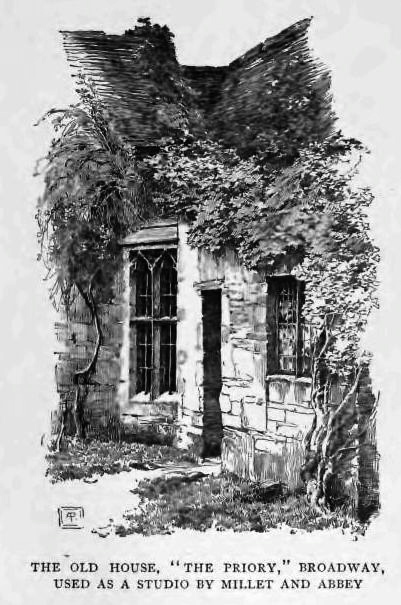

The Old House, “the Priory,” Broadway, used as a studio by Millet and Abbey. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

It has sometimes happened that the distinguished draughtsman or painter has been born in the studio and fed, as it were, from the palette, but in the great majority of cases he has been nursed by the profane, and certainly, on the doctrine of mathematical chances, a Philadelphia genius would scarcely be an exception. Mr. Abbey was fortunate, however, in not being obliged to lose time; he learned how to swim by jumping into deep water. Even if he had not known by instinct how to draw, he would have had to perform the feat from the moment that he found himself attached to the "art department" of a remarkably punctual periodical. In such a periodical the events of the day are promptly reproduced; and with the morrow so near the day is necessarily a short one—too short for gradual education. Such a school is not, no doubt, the ideal one, but in fact it may have a very happy influence. If a youth is to give an account of a scene with his pencil at a certain hour—to give it, as it were, or perish—he will have become conscious, in the first place, of a remarkable incentive to observe it. so that the roughness of the foster-mother who imparts the precious faculty of quick, complete observation is really a blessing in disguise. To say that it was simply under this kind of pressure that Mr. Abbey acquired the extraordinary refinement which distinguishes his work in black and white is doubtless to say too much; but his admirers may be excused, in view of the beautiful result, for almost wishing, on grounds of patriotism, to make the training, or the absence of training, responsible for as much as possible. For as no artistic genius that our country has produced is more delightful than Mr. Abbey's, so, surely, nothing could be more characteristically American than that it should have formed itself in the conditions that happened to be nearest at hand, with the crowds, streets and squares, the railway stations and telegraph poles, the wondrous sign-boards and triumphant bunting, of New York for the source of its inspiration, and with a big hurrying printing-house for its studio. If to begin the practice of art in these conditions was to incur the danger of being crude, Mr. Abbey braved it with remarkable success. At all events, if he went neither I through the mill of Paris nor through that of Munich, the writer of these lines more than consoles himself for the accident. His talent is unsurpassably fine, and yet we reflect with complacency that he picked it up altogether at home. If he is highly distinguished he is irremediably native, and (premising always that I speak mainly of his work in black and white) it is difficult to see, as we look, for instance, at the admirable series of his drawings for "She Stoops to Conquer," what more Paris or Munich could have done for him. There is a certain refreshment in meeting an American artist of the first order who is not a pupil of Gérôme or of Cabanel.

Of course, I hasten to add, we must make our account with the fact that, as I began with remarking, the great development of Mr. Abbey's powers has taken place amid the brown old accessories of a country where that eighteenth century which he presently marked for his own are more profusely represented than they have the good-fortune to be in America, and consequently limit our contention to the point that his talent itself was already formed when this happy initiation was opened to it. He went to England for the first time in 1878. but it was not all at once that he fell into the trick, so irresistible for an artist doing his special work, of living there, I must forbid myself every impertinent conjecture, but it may be respectfully assumed that Mr. Abbey rather drifted into exile than committed himself to it with malice prepense. The habit, at any rate, to-day appears to be confirmed, and, to express it roughly, he is surrounded by the utensils and conveniences that he requires. During these years, until the recent period when he began to exhibit at the water-color exhibitions, his work has been done principally for Harper's Magazine, and the record of it is to be found in the recent back volumes. I shall not take space to tell it over piece by piece, for the reader who turns to the Magazine will have no difficulty in recognizing it. It has a distinction altogether its own; there is always poetry, humor, charm, in the idea, and always infinite grace and security in the execution.

As I have intimated, Mr. Abbey never deals with the things and figures of to-day; his imagination must perform a wide backward journey before it can take the air. But beyond this modern radius it breathes with singular freedom and naturalness. At a distance of fifty years it begins to be at home; it expands and takes possession; it recognizes its own. With all his ability, with all his tact, it would be impossible to him, we conceive, to illustrate a novel of contemporary manners; he would inevitably throw it back to the age of hair-powder and post-chaises. The coats and trousers, the feminine gear, the chairs and tables of the current year, the general aspect of things immediate and familiar, say nothing to his mind, and there are other interpreters to whom he is quite content to leave them. He shows no great interest even in the modern face, if there be a modern face apart from a modern setting; I am not sure what he thinks of its complications and refinements of expression, but he has certainly little relish for its banal, vulgar mustache, its prosaic, mercantile whisker, surmounting the last new thing in shirt-collars. Dear to him is the physiognomy of clean-shaven periods, when cheek and lip and chin, abounding in line and surface, had the air of soliciting the pencil. Impeccable as he is in drawing, he likes a whole face, with reason, and likes a whole figure; the latter not to the exclusion of clothes, in which he delights, but as the clothes of our great-grandfathers helped it to be seen. No one has ever understood breeches and stockings better than he, or the human leg, that delight of the draughtsman, as the costume of the last century permitted it to be known. The petticoat and bodice of the same period have as little mystery for him, and his women and girls have altogether the poetry of a by-gone manner and fashion. They are not modern heroines, with modern nerves and accomplishments, but figures of remembered song and story, calling up visions of spinet and harpsichord that have lost their music today, high-walled gardens that have ceased to bloom, flowered stuffs that are faded, locks of hair that are lost, love-letters that are pale. By which I don't mean that they are vague and spectral, for Mr. Abbey has in the highest degree the art of imparting life, and he gives it in particular to his well-made, blooming maidens. They live in a world in which there is no question of their passing Harvard or other examinations, but they stand very firmly on their quaintly-shod feet. They are exhaustively "felt," and eminently qualified to attract the opposite sex, which is not the case with ghosts, who, moreover, do not wear the most palpable petticoats of quilted satin, nor sport the most delicate fans, nor take generally the most ingratiating attitudes.

The best work that Mr. Abbey has done is to be found in the succession of illustrations to "She Stoops to Conquer;" here we see his happiest characteristics and—till he does something still more brilliant—may take his full measure. No work in black and white in our time has been more truly artistic, and certainly no success more unqualified. The artist has given us an evocation of a social state to its smallest details, and done it with an unsurpassable lightness of touch. The problem was in itself delightful—the accidents and incidents (granted a situation de comédie) of an old, rambling, wainscoted, out-of-the-way English country-house, in the age of Goldsmith. Here Mr. Abbey is in his element—given up equally to unerring observation and still more infallible divination. The whole place, and the figures that come and go in it, live again, with their individual look, their peculiarities, their special signs and oddities. The spirit of the dramatist has passed completely into the artist's sense, but the spirit of the historian has done so almost as much. Tony Lumpkin is, as we say nowadays, a document, and Miss Hardcastle embodies the results of research. Delightful are the humor and quaintness and grace of all this, delightful the variety and the richness of personal characterization, and delightful, above all, the drawing. It is impossible to represent with such vividness unless, to begin with, one sees; and it is impossible to see unless one wants to very much, or unless, in other words, one has a great love. Mr. Abbey has evidently the tenderest affection for just the old houses and the old things, the old faces and voices, the whole irrevocable human scene which the genial hand of Goldsmith has passed over to him, and there is no inquiry about them that he is not in a position to answer. He is intimate with the buttons of coats and the buckles of shoes: he knows not only exactly what his people wore, but exactly how they wore it, and how they felt when they had it on. He has sat on the old chairs and sofas, and rubbed against the old wainscots, and leaned over the old balusters. He knows every mended place in Tony Lumpkin's stockings, and exactly how that ingenuous youth leaned back on the spinet, with his thick, familiar thumb out, when he presented his inimitable countenance, with a grin, to Mr. Hastings, after he had set his fond mother a-whimpering. (There is nothing in the whole series, by-the-way, better indicated than the exquisitely simple, half-bumpkin, half-vulgar expression of Tony's countenance and smile in this scene, unless it be the charming arch yet modest face of Miss Hardcastle, lighted by the candle she carries, as, still holding the door by which she comes in, she is challenged by young Mar-low to relieve his bewilderment as to where he really is and what she really is.) In short, if we have all seen "She Stoops to Conquer" acted, Mr. Abbey has had the better fortune of seeing it off the stage; and it is noticeable how happily he has steered clear of the danger of making his people theatrical types—mere masqueraders and wearers of properties. This is especially the case with his women, who have not a hint of the conventional paint and patches, simpering with their hands in the pockets of aprons, but are taken from the same originals from which Goldsmith took them.

If it be asked on the occasion of this limited sketch of Mr. Abbey's powers where, after all, he did learn to draw so perfectly, I know no answer but to say that he learned it in the school in which he learned also to paint (as he has been doing in these latest years, rather tentatively at first, but with greater and greater success)—the school of his own personal observation. His drawing is the drawing of direct, immediate, solicitous study of the particular case, without tricks or affectations or any sort of cheap subterfuge, and nothing can exceed the charm of its delicacy, accuracy and elegance, its variety and freedom, its clear, frank solution of difficulties. If for the artist it be the foundation of every joy to know exactly what he wants (as I hold it is indeed), Mr. Abbey is, to all appearance, to be constantly congratulated. And I apprehend that he would not deny that it is a good-fortune for him to have been able to arrange his life so that his eye encounters in abundance the particular cases of which I speak. Two or three years ago, at the Institute of Painters in Water-colors, in London, he exhibited an exquisite picture of a peaceful old couple sitting in the corner of a low, quiet, ancient room, in the waning afternoon, and listening to their daughter as she stands up in the middle and plays the harp to them. They are Darby and Joan, with all the poetry preserved; they sit hand in hand, with bent, approving heads, and the deep recess of the window looking into the garden (where we may be sure there are yew-trees clipped into the shape of birds and beasts), the panelled room, the quaintness of the fireside, the old-time provincial expression of the scene, all belong to the class of effects which Mr. Abbey understands supremely well. So does the great russet wall and high-pitched mottled roof of the rural almshouse which figures in the admirable water-color picture that he exhibited last spring. A group of remarkably pretty countrywomen have been arrested in front of it by the passage of a young soldier—a raw recruit in scarlet tunic and white ducks, somewhat prematurely conscious of military glory. He gives them the benefit of the goose-step as he goes; he throws back his head and distends his fingers, presenting to the ladies a back expressive of more consciousness of his fine figure than of the lovely mirth that the artist has depicted in their faces. Lovely is their mirth indeed, and lovely are they altogether. Mr. Abbey has produced nothing more charming than this bright knot of handsome, tittering daughters of burghers, in their primeval pelisses and sprigged frocks. I have, however, left myself no space to go into the question of his prospective honors as a painter, to which everything now appears to point, and I have mentioned the two pictures last exhibited mainly because they illustrate the happy opportunities with which he has been able to surround himself. The sweet old corners he appreciates, the russet walls of moss-grown charities, the lowbrowed nooks of manor, cottage and parsonage, the fresh complexions that flourish in green, pastoral countries where it rains not a little—every item in this line that seems conscious of its pictorial use appeals to Mr. Abbey not in vain. He might have been a grandson of Washington Irving, which is a proof of what I have already said, that none of the young American workers in the same field have so little as he of that imperfectly assimilated foreignness of suggestion which is sometimes regarded as the strength, but which is also in some degree the weakness, of the pictorial effort of the United States. His execution is as sure of itself as if it rested upon infinite Parisian initiation, but his feeling can best be described by saying that it is that of our own dear mother-tongue. If the writer speaks when he writes, and the draughtsman speaks when he draws. Mr. Abbey, in expressing himself with his pencil, certainly speaks pure English, He reminds us to a certain extent of Meissonier, especially the Meissonier of the illustrations to that charming little volume of the Conies Rémois, and the comparison is highly to his advantage in the matter of freedom, variety, ability to represent movement (Meissonier's figures are stock-still), and facial expression—above all, in the handling of the female personage, so rarely attempted by the French artist. But he differs from the latter signally in the fact that though he shares his sympathy as to period and costume, his people are of another race and tradition, and move in a world locally altogether different. Mr. Abbey is still young, he is full of ideas and intentions, and the work he has done may, in view of his time of life, of his opportunities and the singular completeness of his talent, be regarded really as a kind of foretaste and prelude. It can hardly fail that he will do better things still, when everything is so favorable. Life itself is his subject, and that is always at his door. The only obstacle, therefore, that can be imagined in Mr. Abbey's future career is a possible embarrassment as to what to choose. He has hitherto chosen so well, however, that this obstacle will probably not be insuperable.

Last modified 30 November 2012