rban apocalypse is a specific subgenre of apocalyptic fiction, a variety of prophetic literature. In the Book of Revelation (the last Book of the New Testament), the burning of Babylon is a significant apocalyptic event symbolizing the final destruction of a powerful, corrupt city. The destruction or decay of a city, reflecting environmental disaster or societal collapse, has become a favourite theme of modern dystopian literature. The concept of urban apocalypse, where cities face destruction or catastrophe, has roots in various narratives, including early dystopian fantasies of the possible extinction of humanity, among which Mary Shelley's The Last Man (1826) is a prominent precursor. The fascination with urban apocalypse has also been shaped by real-world events like the Lisbon earthquake in 1755. Dystopian destruction of cities in fiction often presents urban environments as centres of uncontrolled technological growth, overpopulation, air and water pollution, increased social inequality, moral decay, and decline in quality of life.

London as a setting of urban apocalypse

London has frequently been depicted as a setting of urban apocalypse in this kind of literature. In his poem "London" (1794) from Songs of Experience William Blake utilized the city as a powerful symbol of social injustice, human suffering and the oppressive forces of the Industrial Revolution. The poem describes the poet's experience of walking through the dismal streets of England's capital. The apocalyptic portrayal of London as a virtual "modern Babylon" often stems from a fascination with the city's vulnerable grandeur, which makes it susceptible to various environmental and social problems. Authors like Charles Dickens in Oliver Twist (1838) and Bleak House (1853), H.G. Wells in The Time Machine (1895) and The War of the Worlds (1897), and Arthur Conan Doyle in his Sherlock Holmes stories, portrayed London as a dark, monstrous place, foreshadowing anxieties about social inequality and urban decay. Several other dystopian works depicted various environmental catastrophes that afflicted London, for example, Richard Jefferies's After London; or Wild England (1885), Robert Barr's The Doom of London (1892) and Grant Allen's The Thames Valley Catastrophe (1897). In 1874, a Scottish-born poet James Thomson (1834–1882), who used the pseudonym Bysshe Vanolis, composed a long pessimistic poem "The City of Dreadful Night" in which he alluded to London as a city of despair and loss of belief, in an uncaring urban environment. The poem might be a good predecessor to T. S. Eliot's apocalyptic poem The Waste Land (1922) in which London is depicted as a desolate and spiritually barren "Unreal City."

Apocalyptic visions of William Delisle Hay

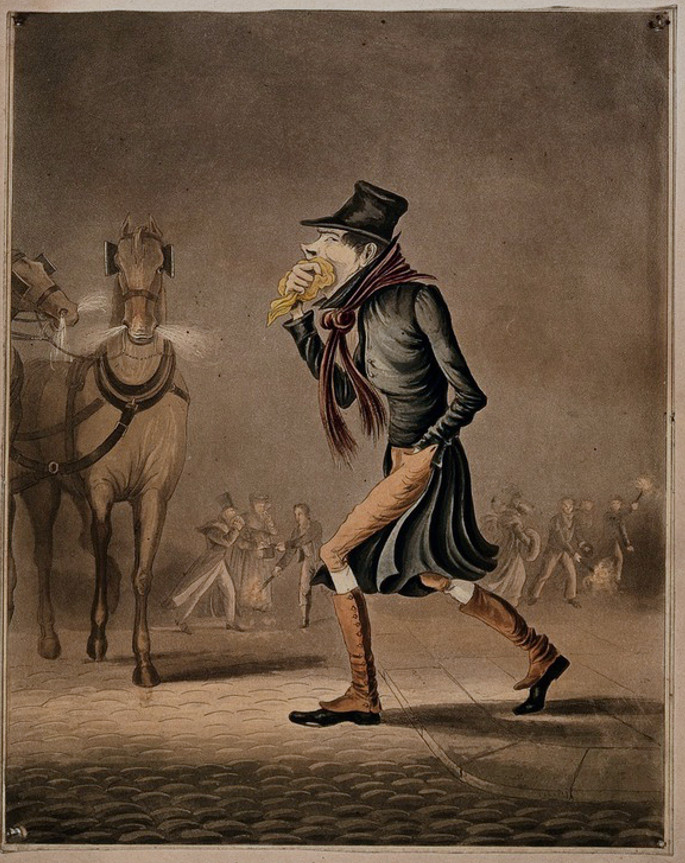

A man covering his mouth with a handkerchief, walking through a smoggy London street. Coloured aquatint from 1862. Source: Wellcome Library, public domain.

Hay's moralistic novella of urban apocalypse, written in the wake of the worst killer fog in London of 1879–80, recounts the fictional destruction of the British capital by a thick soot-filled fog caused by unchecked urban and industrial pollution. At the end of the nineteenth century Londoners consumed vast quantities of coal for the purpose of heating their homes and preparing food. As a result, the fumes from coal burning, mixed with fog, created a dangerous type of air pollution later known as smog. In 1879, a year before the publication of The Doom, London fogs caused an unprecedented number of deaths. In Hay's novella this lethal fog, containing fumes from massive coal burning and industrial emissions, first chokes to death the residents of the poorest quarter of London – the East End – before spreading overnight to other parts of the overpopulated city. The toxic fog caused a mass suffocation of almost half of the population and exodus in panic of the survivors, including the narrator. Having escaped from London the narrator seeks refuge in rural and idyllic New Zealand and from the perspective of some sixty years later provides to his grandchildren a detailed account of the social and environmental causes of this disaster which happened in 1882. The narrator is highly critical of London's unrestrained urban development which has produced not only lethal smog but also poverty, moral decay and crime. He perceives London as a Babylonian hive of corruption, societal decline, vice, debauchery and rampant prostitution:

A London fog was no mere mist; it was the heavy mist, in the first place, that we are accustomed to in most latitudes, but it was that mist supercharged with coal smoke, with minute carbonaceous particles, "grits" and "smuts," with certain heavy gases, and with a vast number of other impurities. It was chiefly the result of the huge and reckless consumption of coal carried on over the wide-extending city, the smoke from which, not being re-consumed or filtered off in any way, was caught up retained by the vapour-laden air. The fog was the most disagreeable and dangerous of all the climatic sufferings that Londoners had to bear. It filled the nostrils and air passages of those who breathed it with soot, and choked their throats and lungs with black, gritty particles, causing illness and often death to the aged, weakly and ailing; it also caused headaches, and oppression, and all the symptoms that tell of the respiration of vitiated air. [21-22]

John Tenniel's depiction of the London fog in the Punch of 13 November 1880 [Click on the image for more information].

In The Doom of the Great City the narrator also puts blame on the urban lifestyles of residents. London is described as "foul and rotten to the very core, and steeped in sin of every imaginable variety" (10), where prostitution flourished abundantly due partly to "uncurbed licentiousness of the men" and "a result of unwise regulations of Government" (17). After a short presentation of his life in London and a discussion of the effect of polluted air on residents, the narrator recollects the nightmarish scenes while he was walking through desolate streets during the disaster looking for his mother and sister. To his horror, he could not spot any living people. There was carnage everywhere. Dead bodies lined the streets and buses were full of dead passengers. When he entered a tavern, he saw only corpses:

One place I knew slightly, a tavern-restaurant, where I had occasionally dined or supped with acquaintances. Thither I bent my steps, picking my way in shivering dread among the corpses that strewed the way – aye! strewed the pavement and the roadway so thickly, O God! so thickly! Somehow I think I must have hoped to find there friendly, sympathizing, living faces; I know not else why I, a lonely wanderer among those thousand mute, stricken victims, should have been seized with another soul-shaking shock, another paroxysm of maddening fear. I had entered the half-open doors of the restaurant, and passed within the bar, where still many of the gas-lamps burnt brightly, mixing with the murky daylight and adding a baleful ghastliness to the scene. No voice, no sound were there to welcome or to check me. I stood unheeded in a house of the dead. Behind the bar a heap of women's clothes huddled in a corner caught my eye: I needed not to look more closely to see that it was a barmaid, for nearer to me was another, drawn down as though by some unseen force from behind, her hands still grasping the handles of the beer-engine, her head fallen back upon her shoulders, her body half-hanging, half-crouched upon the floor. Poor girls! The last time I had seen them only a few days before – they had stood there in all vanity of the youth and beauty, decked with flowers, cheap jewellery, and flashy clothes, smiling on the customers they supplied, bandying "chaff" with their admirers, and listening greedily to the vapid compliments of the boozy dandies, some of whose bodies now lay prostrate at my feet. So had they been occupied up to the sudden awful moment when the FOG-KING had closed down upon his prey. I dared not pass beyond the threshold house, yet the one rapid glance that my eye took scene of the within sufficiently impressed its details on my memory. There were half-empty glasses upon the counter, those who had been drinking from them lying stark upon the floor; men in all the frippery of evening dress, the cigar or cigarette just fallen from their twisted lips…. [46–47]

Finally, when he reached his home, he saw in horror that his mother and sister were choked to death in front of the hearth:

At length I reached our home; I entered the house and descended the basement where we dwelt. Impatiently and fearfully I opened the door and passed into the sitting-room. Yes, there they were. The fire was cold and gray, but the cat lay curled upon the rug in her accustomed place. In the armchair sat my mother, and beside her, on a stool, my sister, just as they often loved to sit, with arms embracing each other. Was it my voice that broke the horrid stillness of the room – so hoarse, so changed? "Mother! sister! darlings!" No answer. Nearer I went, treading slowly and tremblingly. Again my hoarse accents jarred the heavy air as I knelt and took my mother's hand. "Mother! sister! awake!"

Ah! God of mercy! The horrid truth came home to me at last. Dead! dead!! [51–52]

In The Doom the narrator implies that the apocalyptic annihilation of London was the result of not only environmental disaster but also of divine retribution for the abominable moral and social degradation of the imperial city. It was not only fog that killed Londoners in a great mass but also a number of vices prevalent among its residents, such as gambling, prostitution and unfair business practices that contributed to the final desolation of the "Great City":

O London! surely, great and manifold as were thy wickednesses, thy crimes, thy faults, who stayed to think of these in the hour of thy awful doom, who dared at that terrible moment to say thy sentence was deserved ? And I, a lingering survivor of thy slain, oh, pity that it should have been my task to tell of thy CORRUPTION, to bear witness to thy PUNISHMENT! [44]

The narrator urges the reader to look critically upon the negative aspects of modern urban life. He sees the direct cause of London's fateful destruction not only in the forces of nature but in human greed which led to uncontrolled urban development and, and consequently, to tragic health hazards. Hay's novella, published in 1882, which received a relatively modest positive reception, remained out of print for over a century, and has only recently been re-published. Today it can be read as an evocative reminder of unsustainable human practices, particularly the excessive burning of fossil fuels that can destroy life on earth.

Links to Related Materials

- Richard Jefferies and Victorian Science Fiction

- Literary Modes (sitemap)

- The Victorian Evironment and Public Health

- Coal (homepage)

Bibliography

Primary source:

Hay, William Delisle. The Doom of the Great City. Being the Narrative of a Survivor Written A.D. 1942. London: Newman and Co. 1880. A new, critical edition by Michael Kramp and Sarita Jayanty Mizin. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2025.

Secondary sources

Beasley, Brett. "Bad Air. Pollution, Sin, and Science Fiction in William Delisle Hay's The Doom of the Great City (1880)." Public Domain Review. 30 September 2015.

Brimblecombe, Peter. The Big Smoke: A History of Air Pollution in London Since Medieval Times. London: Methuen, 1987.

Corton, Christine L. London Fog: The Biography. Harvard University Press, 2017.

Luckin, Bill. "The Heart and Home of Horror: The Great London Fogs of the Nineteenth Century." Social History

Stähler, Axel. "Apocalyptic Visions and Utopian Spaces in Late Victorian and Edwardian Prophecy Fiction." Utopian Studies. Vol. 23, no. 1 (2012): 162–211. Penn State University Press, 2012.

Taylor, Jesse Oak. The Sky of Our Manufacture: The London Fog in British Fiction from Dickens to Woolf. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2016.

Created 7 August 2025