A knowledge of the visual arts has long been considered essential to a full understanding of Middlemarch, and in this paper I hope to demonstrate that this understanding is considerably deepened when we take into account the major role played in the novel by George Eliot's treatment of Pre-Raphaelitism, and in particular her response to one Pre-Raphaelite painting: William Holman Hunt's Awakening Conscience (1853-4).

A knowledge of the visual arts has long been considered essential to a full understanding of Middlemarch, and in this paper I hope to demonstrate that this understanding is considerably deepened when we take into account the major role played in the novel by George Eliot's treatment of Pre-Raphaelitism, and in particular her response to one Pre-Raphaelite painting: William Holman Hunt's Awakening Conscience (1853-4).

Hitherto, analysis of tht role of Pre-Raphaelitism in Middlemarch has been almost exclusively devoted to the ideas expressed by the Nazarene artist Adolf Naumann and his pupil, Will Ladislaw, in the Rome section of the book (chapters 19-22). For this reason I shall begin my examination of the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic in Middlemarch in Rome, with a brief consideration of Eliot's presentation of German Pre-Raphaelitism. While Will Ladislaw has traditionally been regarded as a figure who mediates, however satisfactorily, between Romantic and Victorian aestheticism, my concern is with an area of his artistic development which is often overlooked: his rejection of German Pre-Raphaelitism for its later, English, counterpart.

This shift in Will's sensibilities interestingly reflects the change which occurred in George Eliot's own taste in Pre-Raphaelite art in the 1860s. Eliot's increasing interest in English Pre-Raphaelitism reached its height early in the 1870s when Middlemarch was being written, and is apparent in her presentation of three of its characters: Will Ladislaw, Rosamond Vincy, and Dorothea Brooke.

Finally, I shall consider in detail the implications of the sequence of allusions Eliot makes in Middlemarch to Hunt's Awakening Conscience. Ilese allusions clearly reveal Eliot's considerable indebtedness to John Ruskin for her understanding of Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics. Nevertheless, [52/53] they also demonstrate her unique ability to weave a rich Pre-Raphaelite strand into the complex web of her novel, by making the development of a Pre-Raphaelite sensibility an integral part of Dorothea Brooke's growth in spiritual awareness — what Eliot calls her 'awakening consciousness.'

Chapter 19 of Middlemarch takes 'Mrs Casaubon, bom Dorothea Brooke', on 'her wedding journey to Rome' (219), and begins with a paragraph of narrative which, even by the standards of the rest of the novel, is unusually ostentatious. Repeatedly in Middlemarch the narrator draws attention to the forty year difference between the period when the story is set 1829-32 — and the period in which it was written and published — 1870-2. In chapter 19 the first paragraph serves to contextualise the immensity of the culture shock Dorothea feels on her first visit to Rome, by explaining that 'in those days the world in general was more ignorant of good and evil by forty years than it is at present.' Moving, significantly, from broad moral to art-historical concepts of 'good and evil', the narrator desseribes the state of terrible ignorance in which the British tourist travelled to Europe in the 1820s, knowing nothing of 'Christian art', in particular. Exemplifying the ignorance of this period is 'the most brilliant English critic of the day', William Hazlitt, 'who mistook the flowerflushed tomb of the ascended Virgin' in Raphael's Coronation ofthe Virgin 'for an ornamental vase', thus failing to recognise the floral resurrection symbolism of the painting.

Served by such inept English art criticism as this it is not surprising that travellers such as Mrs Casaubon were completely overwhelmed by Roman culture. However, as chapter 19 is also designed to demonstrate, not all of the inhabitants of the world of the novel are as ignorant as Hazlitt or Dorothea. Blessed with the knowledge of German scholarship deemed so vital in Middlemarch, the Nazarene painter Adolf Naumann and his protégé, Will Ladislaw, see a vision of Dorothea statuesquely but spontaneously posed before the 'reclining Ariadne' in the Vatican Museum, which sends them into an aesthetic ecstacy. Although the narrator is decidedly amused by the ensuing debate between Naumann and Will, in which they offer conflicting Nazarene and Lessingite interpretations of Dorothea and Ariadne, nevertheless their enthusiastic and informed response to Dorothea invests her with a new value hitherto unperceived in Middlemarch. Alerted to the need for a heightened aesthetic awareness by chapter 19, the Victorian reader of Middlemarch would have appreciated the full significnce of the moment when Dorothea comes into conjunction with a work of art and is found to be superior to it, or have fisked being tarred with the same brush as Hazlitt.

Modern readers have been enabled to appreciate fully the significance of the Rome chapters of Middlemarch because of the work of one critic in particular, Hugh Witemeyer. In George Eliot and the Visual Arts [full text] Witemeyer shows that although she was sympathetic towards some of the [53/54] ideas of the German Pre-Raphalites, and modelled the figure of Naumann on the Nazarenes Fuhrich and Overbeck, nevertheless Eliot was ultimately dissatisfied with the Nazarenes' Christian Revivalist aesthetic. In Middlemarch Eliot's criticisms of German Pre-Raphaelitism are articulated by Naumann's apprentice, Will. For although Will portentously tells Dorothea that Naumann is 'one of the chief renovators of Christian art, one of those who had not only revived but expanded that grand conception of supreme events as mysteries at which the successive ages are spectators', he soon reassures her that: 'I am not as ecclesiastical as Naumann, and I sometimes twit him with his excess of meaning'. (ch. 22:245).

Here Will appears to imply the desirability of finding an aesthetic which offers a happy medium between the 'excess of meaning' contained in the Nazarenes' monumental Christian allegories, and Hazlitt's complete failure to find any meaning at all in Raphael's Coronation of the Virgin. In this as in many other respects Will is ahead of his time — in this case because he is saying in 1830 what George Eliot was thinking in the 1870s. In his Introduction to the Penguin edition of Middlemarch W. J. Harvey describes Will as being 'as close in some respects to the Pre-Raphaelites as to the later Romantics' (17). The vagueness of this identification fairly reflects the vagueness of Will's characterisation as an aesthete. Variously perceived in the novel as being Shelleyan and Byronic, Will is a failed De Quincey who may yet become a Chatterton: in short, he is a composite Romantic poet who aspires to be a Pre-Raphaelite painter.

Historically speaking, the Pre-Raphaelite painter whom Will most resembles is Ford Madox Brown. Although Brown was never invited to join the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood when it was formed in September 1848, he was a close associate of theirs and their only link with the Nazarenes, having met Overbeck in Rome and been influenced by him in his work of the 1840s. Having met Overbeck herself in 1860, during the 1860s Eliot also met most of the English Pre-Raphaelites. In 1868 she and Lewes were introduced to the Bume-Joneses, and through them the Leweses soon met William Morris and D.G. Rossetti, thereby completing 'the original circle of the Pre-Raphaelites,' since they 'had already met Holman Hunt in 1864 and Thomas Woolner in 1866'(Witemeyer 16). In June 1870, a year after the gestation of Middlemarch had begun, the Leweses were holidaying in Cromer on the Norfolk coast and 'reading aloud' from Trollope and Balzac, and 'Rossetti's Poems and Morris's Earthly Paradise' (Haight 428). Eliot's increasing social contact with the English Pre-Raphaelites and growing awareness of their literature in this period helps account for her inclusion of a thumbnail history of Pre-Raphaelitism in Middlemarch, but I wish to suggest that the role of Pre-Raphaelitism in the novel goes considerably deeper than this. [54/55]

Commentators have been struck by the similarities between scenes in Middlemarch and specific Pre-Raphaelite paintings, such as Dorothea's boudoir-window view in chapter 28 which reminds Witemeyer (153-55) of Millais's Mariana (1850-51). While Dorothea appears appropriately in this scene as a withdrawn Pre-Raphaelite figure, the robust Mary Garth is explicitly portrayed with Rembrandtesque honesty when compared with the local beauty Rosamond Vincy in chapter 12. Rosamond's preoccupation with her 'hair of infantine fairness" (139-40) in front of her toilette mirror clearly echoes the sinister narcissism of Rossetti's golden-haired Lilith in his sonnet 'Body's Beauty' (Rossetti 100), and the iconography of its companion painting Lady Lilith (1868), which shows Lilith lovingly combing her blond hair before a mirror. (It is possible that the Leweses saw the painting Lady Lilith, or sketches for it, at Rossetti's studio in Chelsea when they visited in January 1870. It was begun in 1864 and finished in 1868, but not sold until Rossetti's death.) When Eliot acknowledged receipt of the copy of Rossetti's Poems in May 1870 which she and Lewes subsequently read at Cromer, Eliot told Rossetti that 'the Sonnets towards "The House of Life" attract me peculiarly' (Letters 5:93). It is not therefore surprising to find that while Rossetti's Lilith weaves a 'bright web' (1. 7) with her hair and is surrounded by her flowers, 'the rose and poppy'(1. 9), in Middlemarch the sylph-like Rosamond exerts her channs on Lydgate by appearing to him 'as if the petals of some gigantic flower had just opened and disclosed her' (ch. 16:188), and by habitually touching her web of 'wondrous hair-plaits' (189).

Commentators have been struck by the similarities between scenes in Middlemarch and specific Pre-Raphaelite paintings, such as Dorothea's boudoir-window view in chapter 28 which reminds Witemeyer (153-55) of Millais's Mariana (1850-51). While Dorothea appears appropriately in this scene as a withdrawn Pre-Raphaelite figure, the robust Mary Garth is explicitly portrayed with Rembrandtesque honesty when compared with the local beauty Rosamond Vincy in chapter 12. Rosamond's preoccupation with her 'hair of infantine fairness" (139-40) in front of her toilette mirror clearly echoes the sinister narcissism of Rossetti's golden-haired Lilith in his sonnet 'Body's Beauty' (Rossetti 100), and the iconography of its companion painting Lady Lilith (1868), which shows Lilith lovingly combing her blond hair before a mirror. (It is possible that the Leweses saw the painting Lady Lilith, or sketches for it, at Rossetti's studio in Chelsea when they visited in January 1870. It was begun in 1864 and finished in 1868, but not sold until Rossetti's death.) When Eliot acknowledged receipt of the copy of Rossetti's Poems in May 1870 which she and Lewes subsequently read at Cromer, Eliot told Rossetti that 'the Sonnets towards "The House of Life" attract me peculiarly' (Letters 5:93). It is not therefore surprising to find that while Rossetti's Lilith weaves a 'bright web' (1. 7) with her hair and is surrounded by her flowers, 'the rose and poppy'(1. 9), in Middlemarch the sylph-like Rosamond exerts her channs on Lydgate by appearing to him 'as if the petals of some gigantic flower had just opened and disclosed her' (ch. 16:188), and by habitually touching her web of 'wondrous hair-plaits' (189).

One particularly seductive strand in the 'mutual web' (ch. 36: 380) woven between Rosamond and Lydgate is Rosamond's musicianship. Indeed, when all the details of their 'young love-making' have been presented in chapter 36, the narrator reveals that 'all this went on in the comer of the drawing-room where the piano stood'. The piano presides over the courtship of Rosamund and Lydgate and makes its next appearance seven chapters later, strategically placed at, the beginning of Book Five, when Dorothea Casaubon visits Dr Lydgate to consult him about her husband's condition, but finds he is 'not at home':

'Is Mrs Lydgate at home? said Dorothea, who had never, that she knew of, seen Rosamond, but now remembered the fact of the marriage. Yes, Mrs Lydgate was at home.

'I will go in and speak to her, if she will allow me. Will you ask her if she can see me — see Mrs Casaubon, for a few minutes?'

When the servants had gone to deliver that message, Dorothea could hear sounds of music through an open window — a few notes from a man's voice and then a piano bursting into roulades. But the roulades broke off suddenly, and then the servant came back saying that Mrs Lydgate would be happy to see Mrs Casaubon . . . [55/56] Dorothea out her hand with her usual simple kindness, and looked admiringly at Lydgate's lovely bride — aware that there was a gentleman standing at a distance, but seeing him merely as a coated figure at a wide angle. The gentleman was too much occupied with the presence of the one woman to reflect on the contrast between the two --a contrast that would certainly have been striking to a calm observer. (469-70)

The social significance of this meeting is registered by the self-conscious formality of Dorothea, whose repeated use of the word 'Mrs' draws attention to the newly-married status of herself and Rosamond, whom she has never met, and prepares the reader for a decorous meeting between two Middlemarch wives. However, the sound of music through an open window, which is suddenly interrupted, combines with Dorothea's sense of awkwardness to create an indefinable impression of unease. This impression is heightened by the formal tone of the narrator who refers to Mrs Lydgate's companion — whom the short-sighted Dorothea cannot identify — first as 'a gentleman' and then as 'the gentleman'. The awkwardness of this repetition draws attention to the narrator's sudden loss of omniscience: she does not know who is in the room with Mrs Lydgate — or she is deliberately not saying.

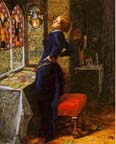

The ambiguous status of Eliot's anonymous 'gentleman' acquires added point when we realise that she is clearly alluding to the scenario in Holman Hunt's painting, The Awakening Conscience. In this picture a gentleman absent-mindedly fingers the keyboard of a piano while gazing blankly at his mistress. As John Ruskin pointed out in a letter published in the Times on May 25 1854: 'the poor girl has been sitting with her seducer, some chance words of the song 'Oft in the the stilly night,'have struck upon the numbed places of her heart' (Ruskin 12:33-4); her conscience is awakened, and she is saved. As the words of her seducer's song strike a chord with the fallen woman, her salvation is also brought about by her sudden vision of the sunlight streaming through the open French windows, which the spectator can see in the mirror at the back of the room, and falling in a shaft of light in the right foreground of the painting.

While these open windows provide the literal source of illumination for Hunt's fallen woman, when it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1854 The Awakening Conscience was shown as the companion piece to Hunt's best known pictorial source of illumination The Light of the World (1851-53). Discussing this painting in a letter to the Times (May 5 1854) which preceded his exegesis of The Awakening Conscience, Ruskin claimed that 'the lantern, carried in Christ's left hand' is the 'light of conscience. Its fire is red and fierce; it falls on the closed door . . . thus marking that the entire awakening of the conscience is not merely to committed, but to hereditary guilt' (12:329-30). In The Awakening Conscience [56/57] the girl's guilt is committed' rather than 'hereditary', but because her doors are opened and not closed, the light which falls on her lurid red carpet triggers 'the entire awakening of the conscience.'

Both Hunt and Ruskin had a considerable impact on the development of George Eliot's aesthetic. Witmeyer believes that Hunt was Eliot's 'favourite Pre-Raphaelite painter' (78), although he notes the same ambivalence towards Hunt's work which characterised her response to ihe Nazarenes. For while she considered Hunt 'one of the greatest painters of the pre-eminently realistic school', Eliot still regarded his portrayal of The Hireling Shepherd (1851-2) as a failure in terms of its realistic portrayal of 'peasants', even though the landscape exhibited 'marvellous truthfulness' ("Natural History of German Life' 268). Eliot's idea of realism was, like Hunt's, profoundly influenced by the writings of Ruskin, and when she writes to Caroline Bray about The Light of the World it is significant that Eliot specifies she has seen it through Ruskin's eyes:

Both Hunt and Ruskin had a considerable impact on the development of George Eliot's aesthetic. Witmeyer believes that Hunt was Eliot's 'favourite Pre-Raphaelite painter' (78), although he notes the same ambivalence towards Hunt's work which characterised her response to ihe Nazarenes. For while she considered Hunt 'one of the greatest painters of the pre-eminently realistic school', Eliot still regarded his portrayal of The Hireling Shepherd (1851-2) as a failure in terms of its realistic portrayal of 'peasants', even though the landscape exhibited 'marvellous truthfulness' ("Natural History of German Life' 268). Eliot's idea of realism was, like Hunt's, profoundly influenced by the writings of Ruskin, and when she writes to Caroline Bray about The Light of the World it is significant that Eliot specifies she has seen it through Ruskin's eyes:

Tell Sara [Hennell] I did notice Hunt's picture, he being an immense admiration of mine, and that I did read Ruskin's letter. I understand all the beauties Ruskin points out, and it is impossible to look at the picture without feeling the power there is in it — but it is too medieval and pietistic to be rejoiced in as a product of the present age. [Letters 2:156]

It is possible that while Eliot reacted to the 'pietistic' medievalism of The Light of the World much as Will did to Naumann's Christian allegories, she was attracted to the modern-life realism of its material counterpart, and companion at the Royal Academy in 1854, The Awakening Conscience. For the religious implications of this painting are sufficiently secularised and humanised to have been acceptable to Eliot's Positivist beliefs. Thus, when Dorothea Casaubon finds out that Will Ladislaw is the 'gentleman'who has been accompanying Mrs Lydgate in her husband's absence, her short-sightedness and the narrator's calculated ignorance combine effectively to transform Will into the anonymous male of Holman Hunt's painting. Realising the compromising nature of the situation he is in, Will tries to extricate himself from it by offering to fetch Lydgate. This offer is refused by a dazed Dorothea who hastily departs to see Lydgate herself, leaving Will to utter the priceless lines: ' 'It is always fatal to have music or poetry interrupted. May I come another day and just finish the rendering of 'Lungi dal caro bene'?" (473)

While Ladislaw contemplates being far from his beloved, Dorothea broods:

Her decision to go, and her preoccupation in leaving the room had come from her sudden sense that there would be a sort of [57/58] deception in her allowing any further intercourse between herself and Will which she was unable to mention to her husband, and already her effand in seeking Lydgate was a matter of concealment. That was all that had been explicitly in her mind; but she had also been urged by a certain discomfort. Now that she was alone in her drive, she heard the notes of the man's voice and the accompanying piano, which she had not much noted at the time, returning on her inward sense; and she found herself thinking with some wonder that Will Ladislaw was passing his time with Mrs Lydgate in her husband's absence. [472]

In Hunt's painting the awakening conscience belongs to a fallen woman. In Middlemarch the only woman in danger of falling is Rosamond Lydgate, yet she remains unrepentant while the conscience of the woman who only fleetingly senses Rosamond's corruption is stricken. Nevertheless, Dorothea feels guilty about her own behaviour because the sounds heard through Lydgate's open window objectify it for her: Mrs Lydgate's compromised situation with Will provides an analogue for Mrs Casaubon's. Furthermore, the fact that this moment of illumination is not pictorial but musical not only ties in neatly with Eliot's depiction of Rosamond as the Middlemarch siren in chapter 31 (333), but also recalls Ruskin's explanation of the iconography of The Awakening Conscience, which passes over the girl's vision of sunlight to argue that her salvation is brought about by what she suddenly hears. Presumably some 'chance words of the song' 'Lungi dal caro bene' strike upon the numbed places of Dorothea's heart.

However, the full significance of this scene only becomes apparent to Dorothea and to the reader when it is repeated in chapter 77. This repetition occurs some time after Dorothea has been widowed and discovered the codicil to Casaubon's will which states that if she should marry Ladislaw she will lose her inheritance. Under a cloud because the Middlemarchers now perceive him to be a bounty hunter, Will Ladislaw prepares to take his leave of Dorothea for an embarrassing second time, having already bid farewell to Middlemarch two months ago. Meanwhile Mrs Cadwallader is moved to express her contempt for Will in these terms in front of Dorothea:

Mr Orlando Ladislaw is making a sad dark-blue scandal by warbling continually with your Mr Lydgate's wife ... It seems nobody ever goes into the house without finding this young gentleman lying on the rug or warbling at the piano. [62:676-77]

With these words ringing in her ears Dorothea returns to Lowick Manor in tears, still trying to believe the best of Will:

but while all the while the remembrance to which there had always clung a vague uneasiness would thrust itself on her attention - the remembrance of that day she had found Will Ladislaw with Mrs Lydgate, and had heard his voice accompanied by the piano. [677-78]

By now it is abundantly clear that Dorothea's encounter with Will and Rosamond in chapter 43 is intended to be central to the novel's development, and not just a vivid but isolated scene. Further proof of the scene's importance is provided when Dorothea finds Will awaiting her at Lowick. Sel f-dramati singly he tells Dorothea that because of what Casaubon's will implies against his 'character" he may never return to Middlemarch. Ladislaw then adds: 'What I care for more than I can evercare for anything else is absolutely forbidden to me'; a cryptic compliment to Dorothea which Will assumes she understands. 'But', the narrator tells us, 'Dorothea's mind was rapidly going over the past with quite another vision than his ... images crowded upon her which left the sickening certainty that Will was referring to Mrs Lydgate.'(681-82)

Remarkably, Dorothea's faith in Ladislaw's love revives, until chapter 77, when he returns to Middlemarch. In chapter 76 Dorothea's sense of sympathy for and 'human fellowship' with the ruined Lydgate is kindled as she reviews 'all the past scenes which had brought' him 'into her memories.' Inevitably one of these scenes is Dorothea's discovery of Will with Rosamund, and the narrator now reveals that

The pain had been allayed for Dorothea, but it had left in her an awakening conjecture as to what Lydgate's marriage might be to him, a susceptibility to the slightest hint about Mrs Lydgate. These thoughts were like a drama to her, and made her eyes bright, and gave an attitude of suspense to her whole frame, though she was only looking out from the brown library onto the turf and the bright green buds which stood against the dark evergreens. [818]

Suddenly, but quite unmistakably, Dorothea's 'awakening conjecture" about the state of Lydgate's marriage causes her to adopt the pose of the girl in The Awakening Conscience, who stands bright-eyed and gazes onto an Edenic garden with promises her redemption. Again, Hazlitt's mistaken non-reading of the floral resurrection symbolism in The Coronation of the Virgin which was held up for our contempt in chapter 19 now reminds us that Eliot's ideal reader will not miss the significance of 'the bright green buds' in either Hunt's painting or her corresponding tableau.

Furthermore, if we turn from the symbolism of Hunt's painting to Ruskin's analysis of it, we also discover the source of Dorothea's sudden [59/60] sense of the 'drama' of Lydgate's marriage. For besides indicating to the Times' readers that 'the fair garden flowers, seen in the reflected sunshine of the mirror... have their language(Ruskin 12:335), Ruskin also invokes the time-honoured Aristotelian principles of tragedy to argue that The Awakening Conscience 'is based on a truer principle of the pathetic than any of the common artistical expedients of the schools.'Ruskin concluded his Times letter by expressing the hope that Hunt's painting would'subdue the severities ofjudgment into the sanctity of compassion.'The sentiments expressed here by Ruskin are fundamentally the same as those expressed by Eliot in her observation that:

If Art does not enlarge man's sympathies, it does nothing morally . . . and the only effect I ardently long to produce by my writings, is that those who read them should be beter able to imagine and tofeel the pains and joys of those who differ from themselves in everything but the broad fact of being struggling erring human creatures. [Letters 3: 111]

With her sympathies enlarged by her new dramatic sense of others' suffering, Dorothea expresses the 'sanctity' of her 'compassion' for Lydgate in characteristically practical, philanthropic fashion.

She lends him �1000 to relieve him of the debt to Bulstrode which has ruined his reputation, and also agrees to speak to Rosamond 'about her husband' (ch. 77:831) in the hope of saving the Lydgates'marriage. In a state of cheerful optimism Dorothea approaches the Lydgates' drawingroom for the second time, where - to her astonishment — she finds that history is repeating itself:

Dorothea had less of outward vision than usual this morning. being filled with images of things as they had been and were going to be. She found herself on the other side of the door without seeing anything remarkable, but immediately she heard a voice speaking in low tones which startled her as with a sense of dreaming in daylight, and advancing unconsciously a step or two beyond the projecting slab of a bookcase, she saw, in the terrible illumination of a certainty which filled up all outlines, something which made her pause motionless, without self-possession enough to speak.

Speaking with his back towards her on a sofa which stood against the wall on a line with the door by which she had entered she saw Will Ladislaw. .. [832]

This scene is almost unbearable to read because, despite the absence of the tell-tale piano music, the ominously sudden recurrence of [60/61] Dorothea's chronic myopia and the low voices behind the door, are painfully familiar. However, the sense of dijd vu inevitably and deliberately attached to this scene by Eliot, is mitigated by the way in which she modifies her characters' responses to it.

In chapter 43 Will is strongly but only momentarily embarrassed by the interruption of his flirtation with Rosamond, while she herself was enjoying the discovery 'that women, even after marriage, might make conquests and enslave men'(474). Now, by contrast, both are 'motionless' - frozen like the girl in Hunt's painting - in a moment of 'terrible illumination'. For Will has finally realised that 'No other woman exists by the side of' Dorothea, and he tells Rosamond so. Thus disillusioned, the narrator reveals that 'Rosamond ... was almost losing the sense of her identity, and seemed to be waking into some new terrible existence' (835-6).

More remarkable, however, than either of these unprecedented reactions by Rosamond and Will, is Dorothea's delayed response to her second encounter with them, and her traumatic realisation of how much she needs Will:

and now, with a full consciousness which had never awakened before, she stretched out her arms towards him and cried with bitter cries that their nearness was a parting vision: she discovered her passion to herself in the unshrinking utterance of despair. [Ch. 80:844]

By the time this moment of revelation occurs, the phrase 'awakened consciousness' and its variants, has acquired a powerful resonance. For the central story of Middlemarch is the story of Dorothea Brooke's 'awakening consciousness' — George Eliot's dechristianised equivalent of Holman Hunt's Awakening Conscience. This awakening begins in Rome when Mrs Casaubon's statuesque reaction to the horrors of her married life is witnessed by a German Pre-Raphaelite and his pupil. But it is not until Dorothea acquires the vision of an English Pre-Raphaelite painter, and his critic, Ruskin, that she is able to overcome her bouts of recurrant myopia.

When Dorothea awakes from her night of despair at the,end of the novel she has 'the clearest consciousness that she' is 'looking into the eyes of sorrow'(845). In his analysis of The Awakening Conscience, Ruskin says that 'even to the mere spectator a strange interest exalts the accessories of a scene in which he bears witness to human sorrow'. Now realising that in her encounter with Will and Rosamond she had really only been a 'mere spectator' Dorothea began now to live through that yesterday morning again, forcing herself to dwell on every detail and its possible meaning. [61/62] Was she alone in that scene? Was it her event only? She forced herself to think of it as bound up with another woman's life. .

Having successfully applied these Ruskinian principles to the scene she witnessed in the Lydgates' drawing-room, Dorothea sees another vision, as for the last time Eliot evokes Hunt's Awakening Conscience and invokes Ruskin:

there was a light piercing into the room. She opened her curtains, and looked out towards the bit of road that Jay in view, with fields beyond, outside the entrance-gates. On the road there was a man with a bundle on his back and a woman carrying her baby ... She was part of that involuntary, palpitating life, and could neither look on it from her luxurious shelter as a mere spectator, nor hide her eyes in selfish complaining. [846]

No longer counter among the ranks of Ruskin's mere spectators, Dorothea sets out 'as quietly and unnoticeably as possible'on 'her second attempt to see and save Rosamond' (848). Dorothea's reward for this act is to receive the benefit of Rosamond's one unselfish act in the novel: the liberation of Will Ladislaw to marry her.

Last modified 7 March 2001