The images in this piece were downloaded by the author and can be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, but you might like to cite the source, and link your document to the Victorian Web or cite it in a print one. Click on the thumbnails for larger images.

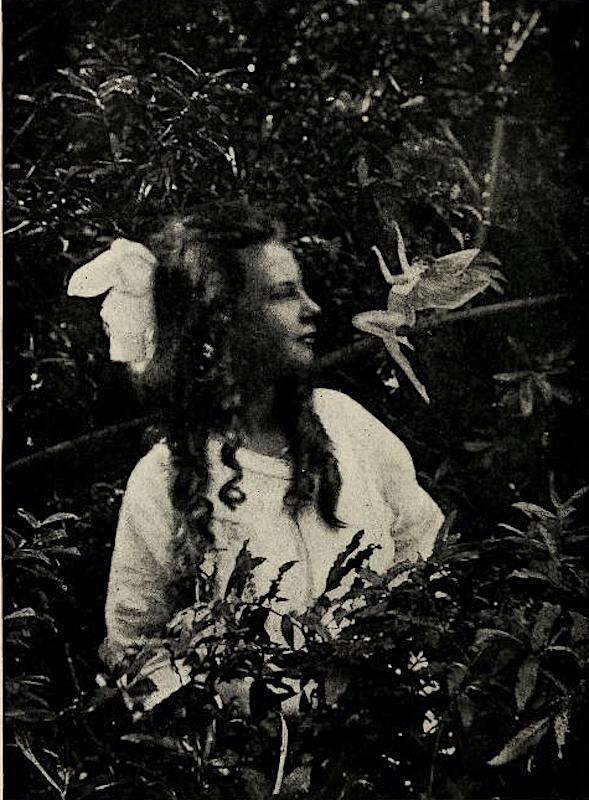

Left: Elsie and the gnome. Source: Doyle, facing p.32. Right: Frances with the dancing fairies. Source: Doyle, facing p.49.

In 1917, a girl called Elsie Wright was sixteen and living in a village called Cottingley in West Yorkshire. Her father Arthur was keen on photography, which at that early stage meant catching images on specially treated glass plates inside a bulky box-camera, then using chemicals to develop the images into black-and-white pictures. Arthur had all the equipment needed. That summer Elsie's nine-year-old cousin Frances Griffiths came to stay. Frances and her mother had just come back from living in Cape Town, South Africa. The cousins enjoyed each other's company, and would often play at the far end of the garden, where there was a small stream. When their mothers scolded them for making their shoes and skirts wet, they insisted that they had to play there, in order to see the fairies. Their mothers were not impressed, so one day, Elsie took her father's camera to prove that it was true.

Arthur Wright developed two pictures for them. One showed Elsie beckoning to a gnome, and the other showed Frances with some dancing fairies. Garden gnomes were already popular in England, but the one with Elsie looked different: it was stepping up to her, and had fairy-like wings. Aware of that his daughter knew something about photography too, and was good at art, her father was highly suspicious. The Victorians had long been fascinated by the idea of fairies, with even the greatest painters and novelists taking them as subjects, and they were still in fashion. Wright knew that the two girls would have had plenty of fairy pictures to copy, so he rummaged around in their room and searched the bottom of the garden hunting for clues that they made cut-outs to stage their scenes. But he found nothing. For the rest of her life, Elsie's mother believed that the fairies in the pictures were real.

Eventually the news got around. At the end of the following year, Elsie sent one of the photographs to a friend back in Cape Town, saying, "It is funny I never used to see them in Africa. It must be too hot for them there" (qtd. in Cooper 141). The real breakthrough came in 1919, when Elsie's mother attended a talk about "Fairy Life." The audience belonged to the Theosophical Society, and believed that human beings were gradually becoming more spiritual — and so might be able to meet such beings. Mrs Wright took the opportunity to show off the fairy pictures, and these were later put on display. In 1920, the girls were encouraged to take three more photographs, which also seemed to show them with the fairies.

Left to right: (a) Frances and the leaping fairy. Source: Doyle, facing p. 65. (b) Fairy offering a posy of hare-bells to Elsie. Source: Doyle, p. 80. (c) Fairies and their sunbath (a kind of cocoon). Doyle: facing p. 81.

Doyle, who was deeply interested in Spiritualism, was delighted to hear of this "evidence" of otherworldly creatures. He was not alone. Experts examined the pictures. Although some remained sceptical (were not the fairies' hairstyles too fashionable?) but others, even those at the Kodak photography company, thought they were genuine. No one was able to prove that they were fakes: even when they were greatly enlarged, no scissor-marks appeared. The celebrated detective-story author was convinced enough to write about them in a respected magazine, and the Cottingley Fairies became a sensation. In 1922, Doyle wrote a book about them: The Coming of the Fairies. This showed the now-famous photographs, giving other examples and the views of other people who believed in them. It seemed that fairies were most likely to be seen on fine days, by children. A leading Theosophist, Edward Gardner, "both the discover of the fairies and a considerable authority upon theosophic teaching" (Doyle 171), described them in the book as being like butterflies in very small human form, and full of a "gladsome, irresponsible joyousness of life" (qtd. in Doyle 174) Noting that people were worried in case all the publicity about them intruded on the delicate little creatures and their world, Gardner said he hoped that we would learn to live happily alongside them in the future. As for Doyle, he said that the whole thing was either "the most elaborate and ingenious hoax ever played upon the public" (Doyle 13) — or a wonderful milestone in human history.

It was years before Elsie and Frances finally confessed that they faked the pictures, and even then the confession was incomplete. In May 1965, Elsie insisted to a Daily Express reporter that the pictures showed "figments of our imagination" (qtd. in Cooper 63), something she repeated in a BBC interview on Nationwide in 1971 (Cooper 121). Then in 1983, she and Frances admitted that they had copied and cut out some figures, taken them down the garden, and propped them up with hatpins (see Hewson 3). But they still said they really had seen fairies, and although Elsie declared later that she never believed in fairies — "Never have and never will" (qtd. in Cooper 140), there is some doubt that that was her true opinion. As for Frances, her daughter said after her mother's death that she had certainly believed in them. The fifth of their pictures seemed to have a special place in their minds.

So there is still a bit of a mystery about this "ingenious hoax." The most interesting part of this mystery is the question of how two girls in those distant days managed to fool so many experts using such simple techniques as cut-outs and hairpins. And why did that fifth fairy, in particular, look so transparent, natural in movement and smooth in outline? It is almost as hard to believe in their photoshopping skills as in the existence of fairies, but, according to Joe Cooper, "on balance, opinion has it that the last photograph looks faked" as well (140). Strange enough in itself, the story of the Cottingley fairies makes a strange little episode in the life of one of the nation's favourite authors.

Related Material

Bibliography

Cooper, Joe. The Case of the Cottingley Fairies. London: Robert Hale, 1990.

Doyle, Arthur Conan. The Coming of the Fairies. New York: George H. Doran, 1922. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Library of Congress. Web. 24 January 2021.

Hewson, David. "Cottingley fairies a fake, woman says." The Times. 18 March 1983: 3.

Last modified 14 November 2013