“… the wayfarer in the toilsome path of human life sees, with each returning sun, some new obstacle to surmount, some new height to be attained” (Nicholas Nickleby, Chapter 53).

n 1872 George Henry Lewes was confused. Two years after Charles Dickens’s death he wondered why, despite their “pervading commonness” (151) and “glaring” defects (143), Dickens’s novels still had “universal power” (144) and “a popularity almost unexampled” (143). In a Fortnightly Review article “Dickens in Relation to Criticism,” Lewes was also bothered by another contradiction. When Dickens was alive the “fastidious” critics (151) spoke and wrote about him with “condescending patronage or sneering irritation,” yet each month would turn around and “bury themselves in the ‘new number’” (143). Though Lewes as critic insists that there can never be enough in Dickens to “move the cultivated mind” (150), as a physiologist and psychologist he keeps probing to understand Boz’s appeal. His most compelling diagnosis is that Dickens’s novels arise from a process close to the hallucinations of the insane (145). Lewes says this gives them a hypnotic power over readers that is fueled by Dickens’s own “unhesitating belief” in “unreal and impossible … distortions of human nature” (146). Lewes even posits that Dickens was “a seer” and characterizes the novels as “visions” (144). But this deepens his confusion because he is admitting that what he considers Dickens’s powerful contributions to literature — capturing “the life everyone knew.” touching “secret streams of sympathy” (147) and stirring “the universal heart” (151) — originated from an “abnormal condition” (144).

Despite his bewilderment Lewes’s characterization of Dickens’s genius helps explain why “even in his early twenties,” as Claire Tomalin says about Pickwick, he “was able to feed his story directly into the bloodstream of the nation” (quoted in Sorensen). It is intriguing to imagine Dickens as a seer and, while reading Nicholas Nickleby, to see this second of his novels as early evidence of an unprecedented vision of modern life. While Dickens was writing Nickleby, Lewes visited him at home in Doughty Street (152). The haughty critic remembers how the cheaply bound books on the shelves “vulgarized the place” and proved that the young author who was experiencing an explosive rise in popularity was “completely outside philosophy, science and the higher literature” (152). He visited again two years later and came away still glum that “the world of thought and passion lay beyond his horizon” (147). Nevertheless in his essay Lewes offers evidence that Dickens did have a vision driven by thought and passion. Where did the vision come from? What experiences were at its heart? Lewes cannot be depended on for answers because it made him uncomfortable to see a sane man reaching so many readers from a trance-like state.

R. W. Buss’s 1875 painting Dickens’s Dream. [Click on all the images to enlarge them, and, except for that of the York Minster window, to find out more about them. — JB.]

Lewes says the young author did not look upon the world as a setting for realistic plots but “as a scene” in itself (152) full of “pictures of common suffering and common joy” (150) and memorable for “the blaze of their illumination” (146). Building on the notion of Dickens’s oeuvre as visionary scenes, one thinks of Buss’s 1875 painting Dickens’s Dream in which, as Leon Litvack explains, Dickens “seems to be in a kind of trance or mesmeric state, with his eyes open” (3) in his study, amazed at characters with “a numinous quality” which “seem to be circulating in a cloud that … fills the room” (1). The idea of Nicholas Nickleby as a vision is supported by the novel’s celebration of the sun. The sun throws light on truths of the world. And if what the sun shows is threatening or disheartening, Dickens’s favored characters start their process of accessing hope. For example, when dawn awakes Nicholas at Dotheboys, Dickens points his reader’s attention to “The first beam of the sun, which lights grim care and stern reality on their daily pilgrimage through the world” (157). This light shows Nicholas his sleeping students but also reveals their collective trauma: “some bore more the aspect of dead bodies than of living creatures; and there were others coiled up into strange and fantastic postures, such as might have been taken as the uneasy efforts of pain to gain some temporary relief” (157). At another sunrise when Nicholas awakens to try to rescue Madeline Bray, he is a “wayfarer in the toilsome path of human life [who] sees, with each returning sun, some new obstacle to surmount, some new height to be attained …. and the light which gilds all nature … seems but to shine upon the weary obstacles that yet lie between him and the grave” (669).

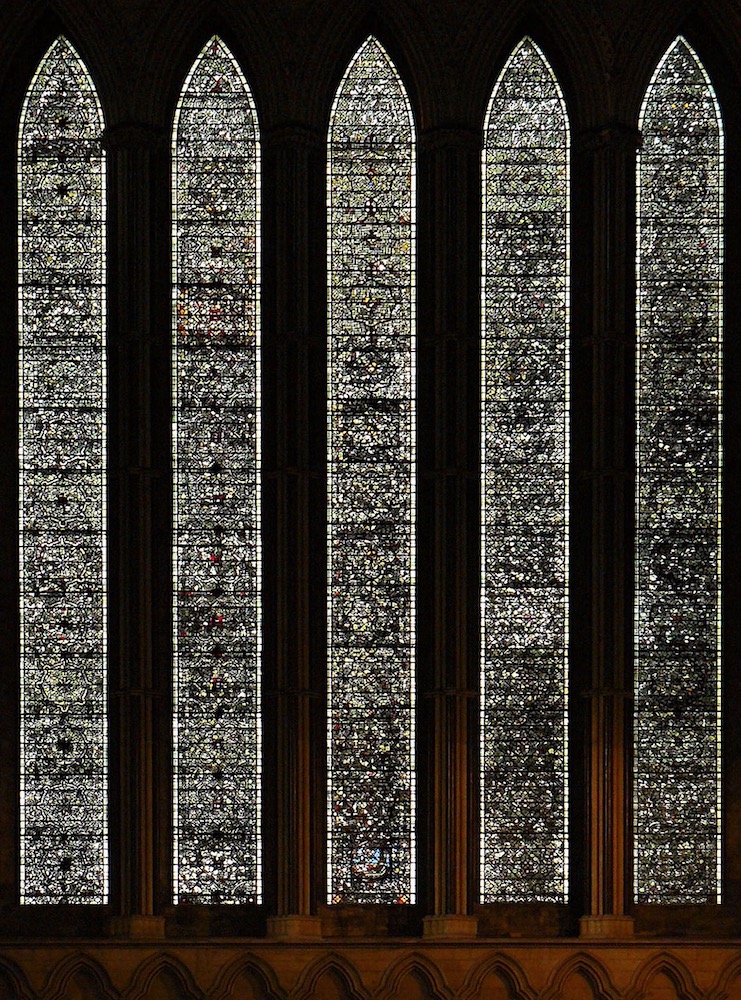

The "Five Sisters" grisaille-glass lancets made of 100,000 or so pieces (photograph by our contributing photographer, Colin Price).

If Dickens knew he had a vision, did he know that Lewes had issues with how he presented it? Imagine the Doughty Street meetings from Dickens’s point of view. The first happened as Dickens was planning and writing Nickleby and it can be surmised that they spoke of it. He might have discovered that the cultivated critic had misgivings. There is a section in Nicholas Nickleby which suggests Dickens did know. Is it possible that this is a response to Lewes’s prejudice? When Nicholas is first leaving home, a fellow traveler tells a tale about five young sisters living near the abbey of York in the sixteenth century, and it seems to duplicate Lewes’s complaints. The sisters’ mother, before her death, had her own kind of vision and directed the girls to work in “discretion and cheerfulness” on five embroideries “of complex and intricate description” (78). This story is based on the renowned stained-glass windows of York Minster, five lancets that together create one abstract vision of interlaced sun and shadow (collectorsweekly.com). The mother stipulates that after the girls have gone “forth into the world, and mingled with its cares and trials,” they should return to “glance at the old work” to “soften our hearts to affection and love” (a fitting description of the effect Dickens desired for this novel). But as the girls ply their needles, a friar appears and plays the same part as the critic Lewes. With his cultivated mind fastened on sin and perfection, he chastises the sisters for “wasting precious hours on this vain trifling” and disparages their art as “an intricate winding of gaudy colors, without purpose or object” (78). This parallels Lewes’s suggestion that Dickens’s novels are “an inextricable web of sense and nonsense (147) …. blurred and formless” (148), which is “the feeling produced by Dickens’s works in many cultivated and critical readers” (148).

Lewes the critic, and his life-partner the celebrated novelist

Two parts of Dickens’s life must have inspired his vision of pain and hope: his alienated months as a boy in the blacking warehouse which must be considered his origin story, and the extraordinary walks through London which he took night and day throughout his life. At the heart of both experiences is what Dickens in “Night Walks” calls “houselessness” (348), the simple fact of wandering late at night in a city but also the vulnerability experienced by people who lack enough physical or psychological support to foster well-being. Juliet John explains that “The Dickens who captured the alienation of the ‘houseless wanderer’ in a ‘great city’ in ‘Night Walks’ is not so familiar to the public: the Dickens who experienced the problems of modernity — alienation, restlessness … loss of the real — rather than solved them, unable to heal or integrate himself, let alone the society he inhabited” (5).

The Warehouse

ickens’s father John was kind and attentive but seemed to always be short of money. Dickens told his biographer and friend John Forster that he experienced benign neglect in the household, and this probably engendered his feeling that stability is fragile and people are generally alone. Thus he declares on the first page of Nickleby, “There are people enough in the world, Heaven knows! …[but] it is extraordinary how a man may look upon the crowd, without discovering the face of a friend” (21). As a boy Dickens had an ominous impression of a “deed” (36), a mysterious “composition with creditors” that went unpaid and got his father arrested and put into the Marshalsea with his wife and daughter, leaving 12-year-old Charles facing aloneness. In Forster’s biography the heart of Chapter II is the “fragment of autobiography” Dickens wrote to lift “the curtain” (69) on this time. His mother insisted that Charles must leave his books and his play and work ten-hour days preparing pots of boot-blacking for sale by wrapping them with oil cloth and paper, “tying them round with a string,” snipping the edges and pasting the label (52). He was “handed over as a lodger to a reduced old lady” where he ate however he could. After a month his father decided his son should come to the prison to live with them but his mother insisted he stay working (68). Forster’s next chapter is called “Start in Life,” but the warehouse is Dickens’s real start. Simple qualitative analysis of the words he uses and the feelings he expresses make it clear this experience formed his outlook on what he calls in Nickleby: “the world.”

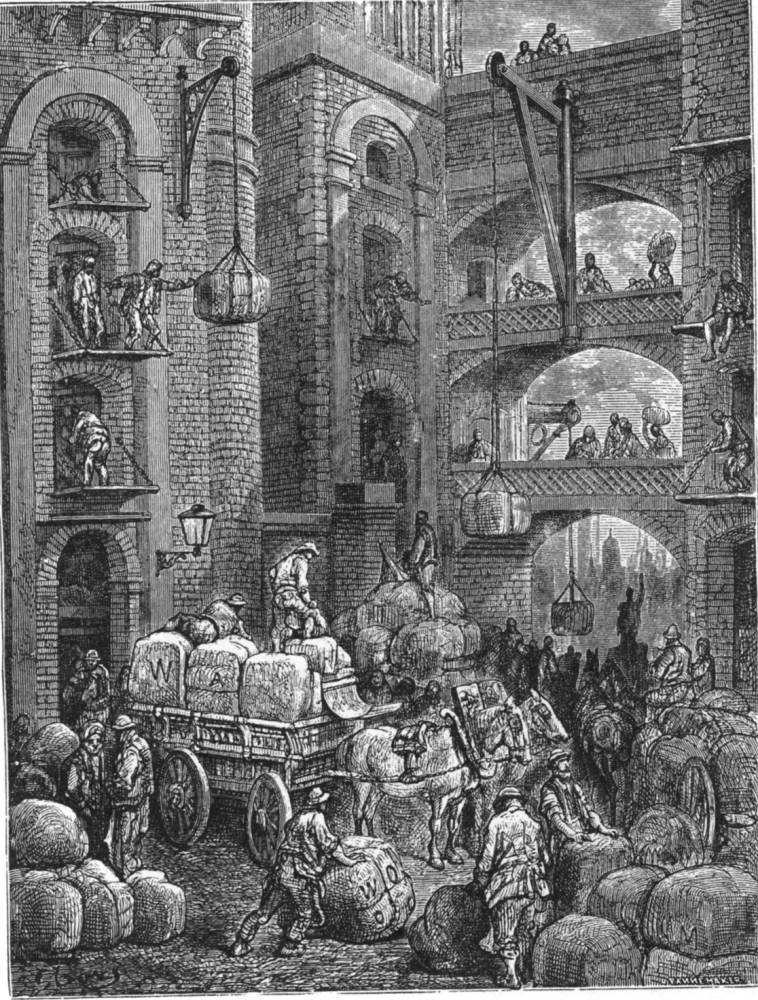

Warehouses by the Thames (further east in the Docklands) in Gustave Doré's Pickle Herring Street, illustration for Douglas Jerrold's London, facing p. 24.

To students of Dickens his simple evocation of the warehouse address has become an incantation, “'Warren's Blacking, 30, Strand’” (Forster, 50). The trauma was so deep he had “no idea how long it lasted; whether for a year, or much more, or less” (69). He “suffered in secret … suffered exquisitely.” And it is striking that for this man of words the ordeal is “utterly beyond my power to tell” (58). The ordeal affected Dickens’s path towards “self-realization” which, as Jacqueline Banerjee explains on this website, is a central concern in Nickleby too. The twelve-year-old got “No advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no support, from any one that I can call to mind, so help me God” (55). It is hard to deny that this is where he saw his vision: happiness crushed in a city that combines neglect with hope. He realized the world rises and falls, things are given and then taken: "The misery … to believe that, day by day, what I had learned, and thought, and delighted in …was passing away from me, never to be brought back any more…. even now, famous and caressed and happy, I often forget in my dreams that I have a dear wife and children; even that I am a man; and wander desolately back to that time of my life" (54).

He was ready to sympathize with others on a grand scale. Clearly Lewes is seeing this too when he highlights the central idea animating Dickens’s vision, that it is “the duty of each man in his own way to make the lot of the miserable Many a little less miserable” (152). Throughout his career the public turned to Dickens regularly to meet characters who are navigating loss and gain in distinctive ways. In Nicholas Nickleby two of these comic characters are Newman Noggs and Miss La Creevy. To Dickens they would be like the clowns he describes in “The Pantomime Of Life,” “supernumeraries in the pantomime of life … who have been thrust into it, with no other view than to be constantly tumbling over each other, and running their heads against all sorts of strange things.” Newman the clerk once had things and position, or, as he puts it, “Once nobody was ashamed – never mind that. It’s all over” (100) while for the humble painter of miniatures Miss La Creevy, “London is as complete a solitude as the plains of Syria” (250). Like Newman, the artist pursues “her lonely, but contented way.” But both of them share the gift of sympathy and are “brimful of the friendliest feelings to all mankind,” and Dickens lets his readers know, “There are many warm hearts in the same solitary guise” (250). Dickens formed a wall of protection from his trauma and forged a vision filled by characters like these who teach stamina to those who need it. It seems that even Lewes’s “cultivated” critics returned to enjoy this process in novel after novel.

The Walks

ickens told Forster that in his dreams he wandered “desolately” to the warehouse time period and on his long walks he also wandered there. That masterful Dickens interpreter G.K. Chesterton, in his chapter on Dickens’s youth in

Victoria Embankment, Doré's illustration for London again, facing p. 33.

In the “Night Walks,” chapter of The Uncommercial Traveler Dickens reveals that “a temporary inability to sleep, referable to a distressing impression, caused me to walk about the streets all night” and this brought him “into sympathetic relations with people.” It is logical that his vision deepened on these walks. According to Edward Grimble of the Dickens Society, Dickens lost “himself in darkness and anonymity [and] facilitated a kind of fugue state, an abandonment of identity,” and “In an 1860 essay entitled ‘Shy Neighbourhoods,’ he describes a thirty-mile journey from central London out to Gad’s Hill, walking ‘without the slightest sense of exertion, dozing heavily and dreaming constantly.’” Grimble writes that “In this oneiric somnambulism, interior and exterior worlds seem to collapse into each other, and Dickens appears to [be] … walking automatically.” More information on the source of his visions appears in Oliver Twist when Dickens states that a potent source of “visionary scenes” is the time between being awake and being asleep, “a kind of sleep that steals upon us sometimes, which, while it holds the body prisoner, does not free the mind from a sense of things about it …. until reality and imagination become so strangely blended” (296). By accessing such a “vague and half-formed consciousness” (278) Dickens could create his unique realism which combines a reporter’s facility for detail with El Greco-like exaggeration. Lewes thought this reality was “abnormal,” but Chesterton cherishes it precisely because it “does not exist in reality” and stems “from a joy so vital and violent that only impossible characters can express that.” This is visionary and can grip readers with “the unbearable realism of a dream.”

An Abstract Vision

hrough the idea of trance, a reader can appreciate the force of the vision in Nicholas Nickleby. Of course for Lewes, though he admits the novels are filled with “salient details” (145), Dickens’s absurdist tragicomedy as well as his appeal to “the sympathy of masses” (143) make for a “web of sense and nonsense.” But when Lewes degrades Dickens’s characters and scenes, calling them “preposterous” and “impossible” (145) he is actually discovering a positive aspect of the vision. Dickens’s London is preposterous. This is true for Nicholas and Kate for whom every experience is a shocking introduction to life but also for Noggs and Smike who feel London’s dangers more keenly and know the long-term damage they cause. And consider Mrs Nickleby’s obsessive patter that seems to contain every piece of English material culture she has ever seen or touched. Dickens’s London is a realistic study, but it is also a clown show and an abstract swirl.

Even the quick allusions in Nickleby to the Biblical Gog and Magog reinforce that London is an abstract scene. Gog and Magog are the ancient “guardians” of London and their effigies are enshrined in Guildhall (Noble), but if one asks Londoners about their historical reality one is presented with a beloved web of sense and nonsense. Yet as Anthony Swindell explains, Gog and Magog have a place in “the repertoire of Western culture,” and in British literature they are “almost always … a means of replenishing or revitalizing present culture.” They originated in Ezekiel 38-39: Gog was an adversary of God and Magog was his homeland. But they turn up in London as two giants defeated by “Brutus the Trojan, the legendary founder of London (Troia Nova)” and forced to guard his new city. To Londoners, they have symbolized human stamina since at least the time of Henry V (Britannica), so they fit nicely into Dickens’s vision. They are mentioned twice in Nicholas Nickleby when a character is offering help or professing love. The first time, Miss La Creevy is offering kindness to Mrs. Nickleby and Kate: “‘If, in all London, or all the wide world besides,’ she promises, ‘there is no other heart that takes an interest in your welfare, there will be one little lonely woman that prays for it night and day.’ With this, the poor soul, who had a heart big enough for Gog, the guardian genius of London, and enough to spare for Magog to boot … sat down in a corner, and had what she termed ‘a real good cry.’” (142). The next time is in the poem by “the gentleman in the small-clothes” which he recites in his manic effort to woo Mrs. Nickleby from atop a garden wall (and his crazy effort is not unsuccessful; she is flattered). He declaims every proof that he is a person of importance, every high personage who can vouch for him and all the luxuries he will provide her and then offers his ultimate flourish, “Gog and Magog, Gog and Magog. Be mine, be mine!” (522). These references are not as weighty as George Eliot’s in Middlemarch when she aligns her heroine’s quest for goodness with Saint Theresa’s. They are comic throwaways. But they anchor two survivors in a folk tradition that promises Londoners know how to get through rough times. Like the allusion to the windows of York Minster and the one to Hans Holbein’s painting Dance of Death mentioned later in this article they show that Lewes was mistaken to claim that in Dickens’s work there is no indication of “the past life of humanity having ever occupied him” (151).

Nicholas and Smike, by Sol Eytinge, 1867, IV, title page.

In Nickleby’s vision London is a daunting monolith, part friend, part monster, and Dickens captures it pictorially from two vantage points, the heights of the suburbs and a fast-moving coach. Nicholas’s story is about “self-realization” as Banerjee shows, and each time the 19-year-old leaves or returns to London — and takes another step towards his identity — Dickens adds a wide-angle portrait of his world. Each rendering is affected by Nicholas’s emotional state, the first is gray and cynical, the second fast and furious. After completing his first rite of initiation by violently defending the rights of the boys at Dotheboys Hall, Nicholas returns to London to face the anger of his uncle and quickly discovers that his next challenge awaits: to save his family he must again separate from them. The narrator accentuates his youthful resilience, “He hailed the next morning when he resolved to quit London,” but then mocks his naivete, pointing out what Nicholas does not yet see, the responsibility he has assumed by taking along the orphan Smike, and that without his uncle’s support there are no guarantees. The more Nicholas learns about Smike, the wiser he becomes. As they hike out of London, he is curious to know the orphan’s origin story, so he asks him, “Have you a good memory?” and receives this sobering reply, “I don’t know…. I think I had once; but it’s all gone now — all gone” (276). This echoes Newman’s complaint about perpetual disconnection. A chastened Nicholas looks back at London, and he can now understand the reason for its gray fog. Though he and Smike are standing on a hill in bright sunlight, below “a dense vapor still enveloped the city they had left, as if the very breath of its busy people hung over their schemes of gain and profit, and found greater attraction there than in the quiet region above” (277).

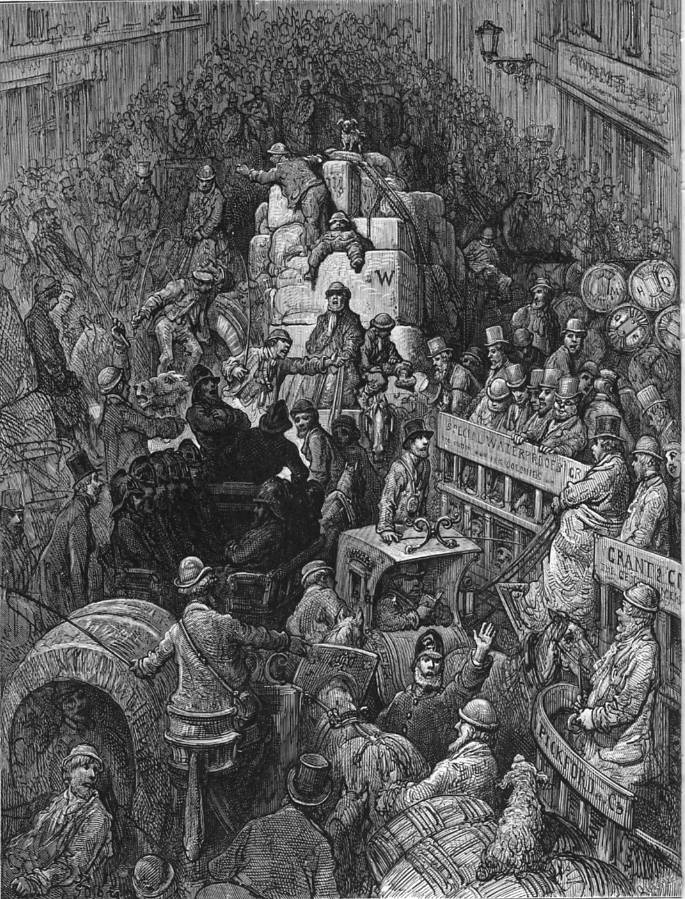

A City Thoroughfare, Doré's frontispiece to Jerrold's London, 1872.

Months later, when Nicholas returns from touring with Crummels’s acting troupe determined to defend his sister from a mysterious threat, Dickens’s vision of London is animated by Nicholas’s impatience and the coach’s speed. We also feel Dickens’s anger as he points a finger at London’s intimidating circle of life from riches to death:

Streams of people apparently without end poured on and on, jostling each other in the crowd and hurrying forward, scarcely seeming to notice …. vehicles of all shapes and makes, mingled up together in one moving mass like running water, lent their ceaseless roar to swell the noise and tumult …. When they dashed by the quickly changing and ever-varying objects it was curious to observe in what a strange procession they passed before the eye …. Emporiums of splendid dresses …Tempting stores of everything … vessels of burnished gold … guns, swords, pistols … engines of destruction … clothes for the newly born, drugs for the sick, coffins for the dead. [400]

In this abstract vision everything is “jumbled each with the other and flocking side by side” (400). Lewes too uses the word jumbled (147), but in a negative way to describe the uncomfortable effect of any Dickens novels on his own senses. Lewes feels accosted and insulted by Dickens’s intersecting images of life, loneliness, and unexpected joy; they dart at him without sufficient authorial explanation, blur his understanding and make him long for “lucid exposition” (147). But as if to scoff at Lewes, Dickens tacks onto the description of the coach ride a last mystical image: London “seemed to flit by in motley dance like the fantastic groups of the old Dutch painter and with the same stern moral for the unheeding restless crowd” (400). This is an allusion to Hans Holbein the Younger’s Dance of Death, a narrative series of woodcuts from the sixteenth century that are both religious and satirical. In the artist’s vision “Death …summons a group of people from all social classes in a dancelike procession” (clevelandart.org) and this ends Dickens’s unsettling vision of London.

Links to related material

- Dickens’s Vision in "Nicholas Nickleby," II: Kate Nickleby and the #MeToo Movement

- The Blacking Factory and Dickens's Imaginative World

- Self-Presentation and Self-Realisation in Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby

Bibliography

Britannica. “Gog and Magog.” Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. 1998. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Gog

Chesterton, Gilbert Keith. Charles Dickens. http://www.online-literature.com/chesterton/charlesdickens/3/

Collectorsweekly.com/stories. “York Minster, Five Sisters’ Window c. 1885.” https://www.collectorsweekly.com/stories/119102-york-minster-five-sisters-window-c-1

Dickens, Charles. Nicholas Nickleby. Barnes and Noble Classics. New York: 2005.

_____. “Night Walks.” All the Year Round. July 21, 1860. Dickens Journals Online. https://www.djo.org.uk/media/downloads/articles/1698_The%20Uncommercial%20Trav eller%20[xii].pdf

_____. Oliver Twist. New York: Barnes and Noble, 2003.

_____. “The Pantomime of Life.” Bentley’s Miscellany. 1837. http://www.online-literature.com/dickens/mudfog/4/

Eliot, George. “The Natural History of German Life.” The Westminster Review, 1856. http://georgeeliotarchive.org/files/original/ab0ce83fbebfa372e5e9a1c55ffcfeb8.pdf

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens. Boston: 1875. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/25851/25851-h/25851-h.htm

Grimble, Edward. “Walking Fast and Far: Dickens, Europe, and Restless Pedestrianism.”

The Dickens Society. May 7, 2018. https://dickenssociety.org/archives/1917

John, Juliet. “Stardust, Modernity, and the Dickensian Brand,” 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century. 14 (2012). https://doi.org/10.16995/ntn.640.

Johnson, E.D.H.

Lewes, George Henry. “Dickens in Relation to Criticism.” Fortnightly Review. February 1872. https://davidcopperfield.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/lewes-dickens-in-relation-to-criticism.pdf

Litvack, Leon. “Dickens’s Dream and the Conception of Character.” The Dickensian. Dickens Fellowship. 2007. https://pureadmin.qub.ac.uk/ws/files/139485399/Dickens_s_Dream_final.pdf

Muller, Jill. Introduction to Nicholas Nickleby. Barnes and Noble Classics. New York: 2005.

Noble, Will. “Gog And Magog: Who Are They and What Have They Got To Do With London?” The Londonist. 2016. https://londonist.com/2016/01/gog-and-magog-who-are-they-and- what-do-they-have-to-do-with-london

Sorensen, Sue. “Reflections on Several Birthdays: Generations of Dickens Criticism.” Academic.edu. 2012. https://www.academia.edu/6726584/Reflections_on_Several_Birthdays_Generations_of_ Dickens_Criticism

Swindell, Anthony. “Gog and Magog in Literary Reception History: The Persistence of the Fantastic.” Journal of the Bible and its Reception. 2016-1003. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbr- 2016-1003

The Charles Dickens Page. Created by David Perdue. “What Was it Like to Live in the London of Charles Dickens?” https://www.charlesdickenspage.com/charles-dickens-london.html

Created 10 March 2022