This essay started life as part of a longer review article entitled "Accidental Tourism" in the Times Literary Supplement of 1 January 2016, pp. 5-8. Links and illustrations have been added to the present version. [Click on all the images to enlarge them, and usually for more information about them.]

Setting Off

y the nineteenth century, London was already much more than the City of London. The urban area had spilled over into the West End, and the Port of London on the East was also expanding. Setting off on his Rural Rides of the 1820s and very early 1830s, the radical politician and pamphleteer William Cobbett was quick to note and deplore the metropolis’s incursions into the surrounding countryside. But the process was just beginning. At this point he himself had a small-holding in Kensington: on passing through nearby Earl's Court in the summer of 1823, he expressed surprise at the state of a wheatfield there: "One would suppose that this must be the finest wheat in the world. By no means. It rained hard, to be sure, and I had not much time for being particular in my survey; but this field appears to me to have some blight in it..." (130). Had Cobbett seen further ahead he would have been even more surprised. The period of London's greatest expansion was yet to come.

Someone waiting to board an omnibus in a Fun cartoon of 1872.

As more and more people moved closer to the city for work, or sought oases of domesticity not too far away from it, a new phenomenon began to emerge: the suburbs. One engine of this change was soon operating. The first horse-drawn omnibuses started plying in that same decade — the 1820s. In fact, this economical form of transport was facilitating urban sprawl at the very time that a certain fledgling journalist, who started work as a shorthand reporter at Doctor's Commons in 1829, was launching his own expeditions. Signing himself “Boz” — a name which may have more than "coincidental consonance" with this new form of conveyance (Fyfe 75) — the younger man made full use of it, alongside Shanks’s pony. As well as exploring the teeming heart of the “Great Wen” from which Cobbett had been so keen to escape, Dickens was intrigued by the parts that lay just beyond it, on its ever-shifting borders.

Life on the Outskirts

In his first-ever published sketch, originally called "A Dinner at Poplar Walk" (1833), but later rechristened "Mr Minns and His Cousin,” Charles Dickens describes Amelia Cottage in Stamford Hill, several miles from central London on a rise to the north-east. It was “a yellow-brick house with a green door, brass knocker, and door-plate, green window-frames and ditto railings, with ‘a garden’ in front, that is to say, a small loose bit of gravelled ground, with one round and two scalene triangular beds, containing a fir-tree, twenty or thirty bulbs, and an unlimited number of marigolds,” not to mention “a Cupid on each side of the door, perched upon a heap of large chalk flints, variegated with pink conch-shells” (Sketches by Boz, 195). Here was the very epitome of suburbia, or, as Ged Pope puts it, "the new mass of lower-middle and working-class suburbs at the metropolitan periphery," growing up during the 1830s onwards (15). Dickens has already caught its character perfectly.

Soon, to borrow words from Dickens’s Mudfog Papers of 1837–38, commuting would become an everyday reality for millions: “trains would start every morning at eight, nine, and ten o’clock, from Camden Town, Islington, Camberwell, Hackney, and various other places in which City gentlemen are accustomed to reside” ("Full Report of the First Meeting of the Mudfog Association," 91-92). The pioneering railway routes boosted the market for new residential developments, and more and more people leased their own Amelia Cottages. London’s tentacles uncoiled on every side, erasing "the boundary of the rural" forever (Fyfe 177). Helping to extend their reach, Kensington High Street tube station was built on the site of Cobbett’s seed-farm in 1867, little more than thirty years after his death.

Dickens’s recognition of such changes sparked much more than a passing interest in them. His earliest vignettes, gathered together in Sketches by Boz in 1836, are not just trailers for the novels. They show him in the role of investigative reporter, a role he would never really abandon, and which he formally renewed outside his novels some twenty years later in the series of pieces published first in his magazine, All the Year Round. The original series appeared in 1860, coming out in one volume in the following year, as The Uncommercial Traveller. A second and third set of articles appeared in 1863 and 1868-69 respectively. In 1868 the earlier two series were also republished in the Charles Dickens Edition again under the title The Uncommercial Traveller. This publication history suggests both their popularity and Dickens's own regard for them. His readers, it seems, enjoyed his observations as much as he enjoyed making them.

The whole sequence of these pieces, as gathered most recently in a new edition edited by Daniel Tyler (see bibliogrpahy), show Dickens's narrator plying his trade throughout for the “firm of Human Interest Brothers” ("His General Line of Business," 5), no longer under the Boz pseudonym and in an only lightly fictionalized way. There are excursions to old haunts at Rochester and Chatham, to Liverpool and even to the Continent, but the London area is still the main focus. Older and wiser now than in the early sketches, less of an early flâneur and more like a man on a mission – or on the Beat, as he puts it in one sketch ("On an Amateur Beat," 336) – he now eschews the middle-class commuter belt in favour of penetrating the "borders of Ratcliffe and Stepney” ("A Small Star in the East," 312; Ratcliffe was a hamlet within Stepney) and other less salubrious regions close to the Thames on the city’s eastern margins. Like Henry Mayhew and the later Victorian slummers or slum-tourists, he delves into a “wilderness of dirt, rags and hunger” ("A Small Star in the East," 312), bringing it even more vividly and dramatically to life than most of his successors would.

On one occasion in Stepney, for example, he glimpses a fading spark of animation in the struggling wife of an unemployed coal-porter. "Her figure, and the ghost of a certain vivacity about her, and the spectre of a dimple in her cheek, carried my memory back to the old days of the Adelphi Theatre” ("A Small Star in the East," 317), where many adaptations of his work had run (including The Peregrinations of Pickwick; or, Boz-i-a-na), but which had been demolished and replaced by a larger theatre in 1858. Two worlds collide momentarily in the wretchedly grimy tenement room. The sense of change, loss and dislocation in his own life, as well as that of the metropolis itself, is palpable.

The pace of change at this time was truly extraordinary. For example, India House, which the Traveller passes in “Wapping Workhouse” early in the first series, has been pulled down by the time he begins the second – while the workhouse itself, which he visits early on, has gone before he finishes the new series (see Tyler ix-x). Like Stepney, Wapping is in the Dockland area of London — hardly what is now thought of as suburbia, but at that time on the very edge of the city. Whitbread's mid-century map of London shows just how much on the edge both Stepney and Wapping were:

Whitbread's New Plan of London, Library of Congress image, with the city boundary in pink.

The four large public parks shown on the map above were themselves considered suburban: when the Uncommercial Traveller has recourse to the authorities after encountering anti-social behaviour in Regent's Park, for instance, he makes (and wins) his case in front of the "suburban Magistrate" ("The Ruffian," 300). Beyond these enclosed green spaces, and below the bend in the river to the east, there are large undeveloped areas. Stepney in Dickens's time extended eastwards to "Bromley Newtown" below Victoria Park in the top right corner, while Wapping was on the river before the bend, opposite a narrowly settled Rotherhithe with fields stretching south towards another "Newtown" — a small and still rudimentary “Peckham Newtown,” also strangely stranded among fields. Interestingly, the Uncommercial Traveller himself talks about the "suburban fields" to which dogs lead their youthful owners "on sporting pretences" ("Shy Neighbourhoods," 99). A similar development was taking place in the south west. There was even a "Battersea Newtown" on the way to the older part of Battersea, marked on the map above, in the lower lefthand corner — all these residential areas still perched in swathes of open land.

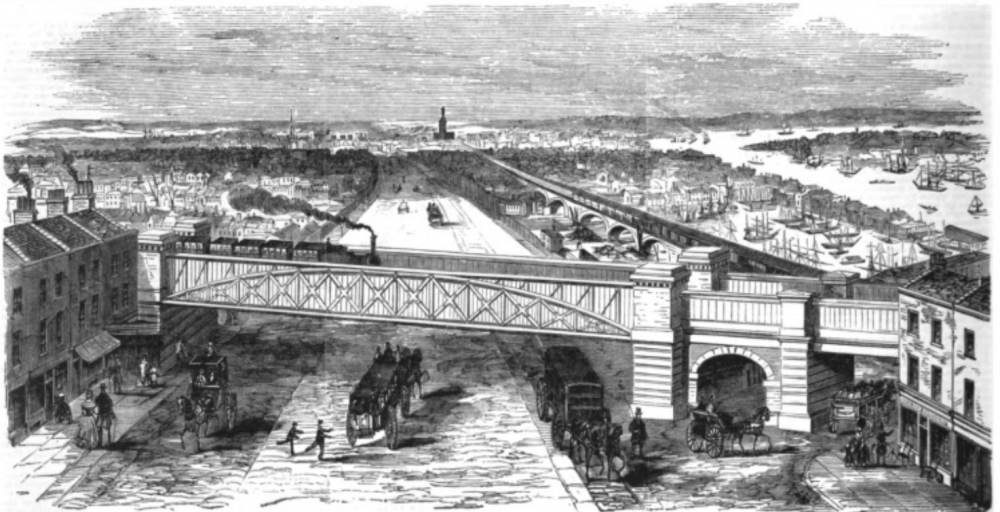

Bow Springs Bridge, Stepney Station: "Having crossed the Commercial-road by Bow Spring Bridge, we soon leave the City and Pool of London behind us, and pass through fields to Bow common" (Illustrated London News, 15 November 1851; emphasis added).

Plague or Haven?

Not only had old ways of life gone, but what replaced them on these city boundaries, whether to the more desirable west and north, or to the poorer outskirts of east and south London, was both disorganised and, at the same time, featureless. These areas could seem ineffably dull, with a dullness that only appeared to increase as early pockets of urban overflow mingled together. This they did at precisely such places as Peckham and Battersea, quickly growing into a solid and, in the opinion of many, benighted mass all around the Wen. Dickens certainly noted their unplanned and undistinguished nature, writing, for example, in Sketches by Boz: "The back part of Walworth, at its greatest distance from town, is a straggling miserable place enough," with most of its recent houses "sprinkled about, at irregular intervals," and "of the rudest and most miserable description." But at the same time he saw some improvement. After all, he says, "five-and-thirty years ago, the greater portion of it was little better than a dreary waste, inhabited by a few scattered people of questionable character, whose poverty prevented their living in any better neighbourhood, or whose pursuits and mode of life rendered its solitude desirable" ("The Black Veil," 230). However it was viewed, the new phenomenon of suburbia that Dickens was describing took far more tenacious root than the American apple-tree cuttings that Cobbett had once so hopefully planted on his Kensington plot.

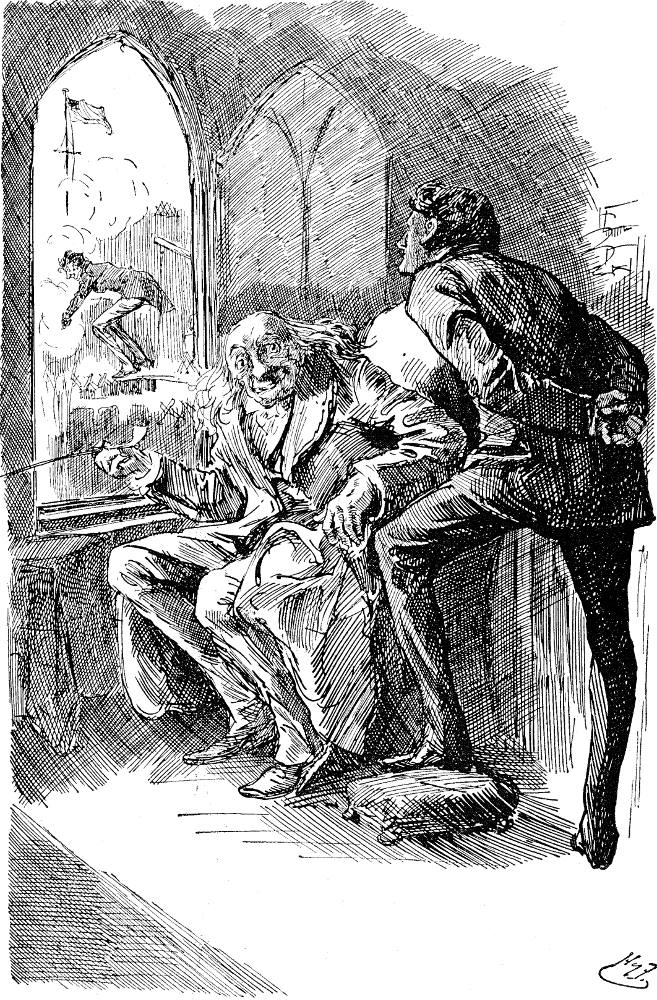

Pip watching the discharge of the gun, by Harry Furniss.

Despite his mixed feelings, the ever-curious Dickens was strangely attracted to these spaces, as Rosemarie Bodenheimer has suggested. More than any of his contemporaries, Bodenheimer argues, it was Dickens who "mapped the expanding city, and created the urban experience of people moving between home and work, home and encounters with others" (149). Part of the attraction was in the very transit. But part was certainly the family home: cut off from work in the new suburbia, here was space for a kind of cosiness that was hard to establish in the city itself, certainly in the East End. This was the location not of the upper-class estate in its rural setting, but of the "humble homes of England, with their domestic virtues and honeysuckle porches" (The Uncommercial Traveller, "Shy Neighbourhoods," 95). The prime example in Dickens's work is Mr Wemmick's "castle" in Great Expectations, "a little wooden cottage in the midst of plots of garden, ... the top of it ... cut out and painted like a battery mounted with guns" (196): here truly is the Englishman's home as the proverbial castle. Like Dickens himself, his illustrator Harry Furniss caught this feeling perfectly when he showed Wemmick's aged father smoking in an armchair by the fire, while the youthful guest, Pip, leans over to look out of one of the quaint gothic windows, and sees Wemmick firing one of the guns. This was the Wemmicks' own protected domestic domain, a freehold property (as Wemmick senior proudly explains) fully fortified against the outside world.

After Dickens

Clearly, the state of town and country, including the areas all around London where the two were meeting and intermingling, had a wide general appeal. Where Dickens led the way, others followed. Wemmick's "castle" gives a foretaste of the Pooters' suburban home, as described by George and Weedon Grossmith in Diary of a Nobody, growing like Dickens's sketches from a periodical series (this time in Punch), and first published in book form in 1892. "The Laurels," at one of the ends of "Brickfield Terrace," has the advantage of being semi-detached rather than attached on both sides. The name of the terrace is a reminder of the flourishing brick industry that supported such new housing estates. This one is in Holloway, to the north of the city, upscale from the east, and eminently suited to white-collar employees like Mr Pooter. It is "a nice six-roomed residence, not counting basement with a front breakfast-parlour. We have a little front garden," explains Pooter, "and there is a flight of ten steps up to the front door; which, by-the-by, we keep locked with the chain up.... We have a nice little back garden which runs down to the railway.... After my work in the City, I like to be at home. What’s the good of a home, if you are never in it? 'Home, Sweet Home,' that’s my motto'" (5-7).

The Pooters' semi-detached suburban home, "The Laurels," in Holloway, north London.

As a reward for good service to his firm at the end of the novel, Pooter is promised the freehold of the house by his employer. He could not be happier:

July 11. — I find my eyes filling with tears as I pen the note of my interview this morning with Mr. Perkupp. Addressing me, he said: “My faithful servant, I will not dwell on the important service you have done our firm. You can never be sufficiently thanked. Let us change the subject. Do you like your house, and are you happy where you are?”

I replied: “Yes, sir; I love my house, and I love the neighborhood, and could not bear to leave it.”

Mr. Perkupp, to my surprise, said: “Mr. Pooter, I will purchase the freehold of that house, and present it to the most honest and most worthy man it has ever been my lot to meet.” He shook my hand, and said he hoped my wife and I would be spared many years to enjoy it.

My heart was too full to thank him; and, see: “You need say nothing, Mr. Pooter,” and left the office. [234-35]

As in Mr Minns's visit to Amelia Cottage, there is undoubtedly an element of mockery here, but it seems more affectionate. Pooter's ambitions are so disarmingly modest, so easily satisfied; his reaction so heartfelt and exultant. It is clear that, for some at least, the margins could be eminently desirable. Writers like Dickens and the Grossmiths may have been taken aback by, and indeed sometimes ambivalent about, the expansion of London into the surrounding countryside. They may have made fun of it. But they saw the need for it. They saw what it offered to the growing middle classes. They understood it. And between them they did help to give suburbia an identity, to offset the dislocation and disconnection attendant on its growth by endowing it with a sense of homeliness. In this respect, then, writing about the new suburbs was "part of a much broader field of human cultural and interpretative work which actively seeks to make the lived environment legible and richly inhabitable" (Pope 209).

As for Dickens, his experience of the margins of the city, on all sides, can be sobering, amusing, heart-warming or a mixture of all three. But to the Uncommercial Traveller these liminal spaces always represent a profit for the “firm of Human Interest Brothers,” of which his readers (who often inhabit such spaces themselves) are the direct beneficiaries.

Links to Related Material

- The Great Housing Boom: Housing in Victorian England

- Homes in the Cities and Suburbs

- Planned Suburbs, Garden Cities and Model Towns (sitemap)

- Garden Suburbs: Architecture, Landscape and Modernity 1880-1940

- Bedford Park, London's First Garden Suburb

- [Review of] Laura Whelan's Class, Culture and Suburban Anxieties in the Victorian Era

- Review of Nathaniel Robert Walker's Victorian Visions of Suburban Utopia: Abandoning Babylon

Bibliography

Bodenheimer, Rosemarie. "London in the Victorian Novel." The Cambridge Companion to the Literature of London. Ed. Leonard Manley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011. 142-159.

Cobbett, William. Rural Rides. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1967.

Dickens, Charles. The Mudfog Papers, etc.. London: Richard Bentley, 1880. Internet Archive, from a copy in the University of California libraries. Web. 26 February 2024.

_____. Sketches by Boz. London: Chapman and Hall, 1854. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Library of Congress. Web. 28 February 2024.

_____. The Uncommercial Traveller. Ed. Daniel Tyler. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Fyfe, Paul. By Accident or Design: Writing the Victorian Metropolis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Grossmith, George and Weedon. Diary of a Nobody. New York: Tait, 1892. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Library of Congress. Web. 28 February 2024.

Pope, Ged. Reading London's Suburbs: from Charles Dickens to Zadie Smith. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Tyler, Daniel. Introduction. The Uncommercial Traveller, by Charles Dickens. Ed. Tyler. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. vii-xxvii.

Whitbread's New Plan of London. Library of Congress. Control Number 2015591076. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g5754l.fi000101. LCCN Permalink: https://lccn.loc.gov/2015591076, No known copyright restrictions.

Created 28 February 2024