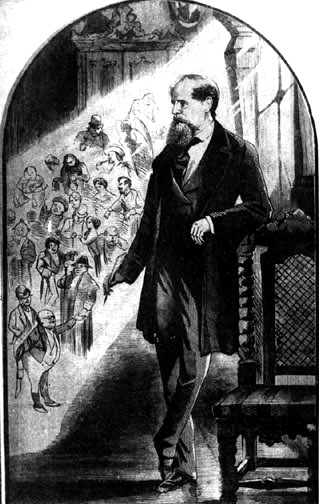

Charles Dickens

June 25 1870

The Tomahawk (London)

[See below the long eulogistic critical essay that appeared in The Tomahawk accompanying this image]

Scanned image and text by George P. Landow.

[This image may be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose.]

What can we say of Charles Dickens that has not been said before, — written by abler pens than ours, felt by tenderer hearts than ours?

We are mere satirists. Our duty is but to tear and rend — to show the hateful face of hypocrisy to the world, to rob Folly of the sound of the bells. What right have we to stand near the great man's grave, to add one wreath of cypress to the immortelles strewn o'er the dead's last resting place?

But little; our mission is with the living, our task a lifelong fight. We have no time for grief, sighs or tears; and yet we cannot let the earth rest on Dickens's grave without writing a few humble words in his honour, — writing them from the heart with faltering pen and trembling hand; writing them in bitter sorrow unbounded, sorrow without end.

In years to come our words may appear extravagant; but now while the loss of our great good novelist is upon us one grief is shared by a people, a race, a world.

Charles Dickens was not only a romancer, he was a mighty teacher, as powerful as the abiest preacher of modern times. His mission was one of mercy. He did not come among us to war with his enemies, to join petty cliques, to support petty coteries. No, his life was spent (ah! how soon!) in showing us that real good might be mingled with apparent bad, how the wealthy man might be a Christian, how the poor man need not always be a brute. He drew nearer to one another class to class; in a word, he taught one half of the world, how the other half lived. This he did without ostentation, without a thought of self. He was proud of his profession, not of his brain; thanked his God for his power to do good, not for his means of gaining fame.

He has gone away for ever from among us, but he has left his books that will bear his name down to generations yet to come. He and his fellow-maker, Thackeray, represent worthily the literature of the century. Macaulay may have been a great historian, but his name will not iive as long as "Charles Dickens." Tennyson may be a great poet, but he wiii be forgotten before "Thackeray" becomes a meaningless word. Who have we to succeed these two great men? Wilkie Collins? Absurd! Charles Reade? Ridlculous! The first is a writer who would delight the heart of the manager of the Ambigue — the second turns "blue book" into romance, poor specimens of human nature into grotesque buriesque. Anthony Trollope can write small beer, and Miss Braddon of the beauties of the limelight and the delight of London Journal society! Who else have we? No one — absolutely no one! it is true — No one!

As we write, the vision of his works passes before us, and we see the creations of his brain in all their unparalleled excellence. Comedy and tragedy, smiles and tears, mirth and pathos.

First there is Pickwick — the great, the good Pickwick. Pickwick who in spite of his smalls and his spectacles and absurd mishaps is a gentieman, a gentleman every inch of him. Near him is Sam Weller, first of humorists, most gentle of satirists, a man whose fund of anecdote would have made the fortune of a rival Percy, whose readiness in the hour of danger would have brought a reputation for the stupidest of generals and most incapable of commanders-in-chief; and there too is Jingle, adventurer and liar, and poor debtor. Ah, there is seen the master hand of Dickens! Who can hate Jingie after that touching scene in White Cross Street? That scene which brings out the struggling good from the mass of bad. There too is Winkle, born onty to illustrate Seymour's pencil; and Snodgrass, and the rival editors, and a score of others. The vision fades and another picture takes its place.

Now we have David Copperfieid, gentlest and kindest of iads, condemning and yet admiring Steerforth, as that headstrong youth denounces the poor usher. Then dear chiidlike Dora appears with her tiny dog, and the two fade away together, and Rosa Dartie — revengefui Rosa Dartle — pours her fierce, pititess invective upon littie Emily's head, and Peggotty wanders once again through the world to find his brother's chiid — the chiid so cruelly lost to him, and Micawber, most hopefui of mortals, "turns up" in Australia, prosperous, happy and conversational; and the vision is crowded with characters — all good, all true, and then it fades away and gives place to another.

Martin Chuzzlewit — old Martin and young Martin, both proud, both firm, both obstinate; and here too is Mark Tapley, who can be jolly under the dismalest of circumstances, and Pecksniff the hypocrite, and Jonas, assassin, and Gamp, the immortal Gamp, snuffy, grinning Gamp — Gamp who is rather more than a man, and just a trifle less than a woman; and Mercy, poor Mercy, and Cherry the shrew. See how they pass away; and here is Dombey — cold, stern Dombey, weeping over the coffin of his little son; and Florence — sweet, patient Florence stands beside him, whispering words of consolation into his grief-dumb ears; and see, there is Captain Cuttle, and the friendly Toots, and the serpent Carker, and Edith, proud and scornful. More yet. —

Nicholas Nickleby at Squeers'. See how wretched the boys are, in spite of the smiles of Miss Fanny, and the brimstone and treacle of the master's wife; and there is John, the general Yorkshire man, and Crummles, with his "real pump and splendid tubs," and poor Smike; and see Mrs. Nickleby, full of anecdotes — so full that they mix together in a sad jumble, reminding one of a badly dressed salad; and there too is Ralph Nickleby — stern Ralph Nickleby, money lender and brute; and Kate, sweet Kate, and Lord Verisopht, and Sir Mulberry Hawk, and again the vision fades.

Little Dorrit is here now, with her patient, loving face, and see the circumlocution office is again open to the public, and shall attempt the solution of that most difficult probiem of how not to do it; and the shadow, — the blighting shadow of the Marshalsea falls across the horizon and fades away.

But why should we write further? is not every character we have mentioned known and admired by the whole nation? Do not the creations of Dickens belong to us, — live among us?

And he has gone! This great Magician of the pen has gone. Writing to the last — good, nobie words, fighting to the iast against Evi1 and Sham. He has gone forever, leaving us to mourn for him; leaving us to sigh as we discover in the Shadow Death, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. [From The Tomahawk (London), 25th June, 1870; Reprinted Wilkins, 187-92].

Bibliography

Wilkins, William Glyde and B. W. Matz. Charles Dickens in Caricature and Cartoon. Boston: The Bibliophile Society, 1924. No. 37.

Victorian

Web

Authors

Charles

Dickens

Gallery

Next

Last modified 19 July 2007