Mrs. Gamp had a large bundle with her, a pair of pattens, and a species of gig umbrella; the latter article in colour like a faded leaf, except where a circular patch of a lively blue had been dexterously let in at the top. She was much flurried by the haste she had made, and laboured under the most erroneous views of cabriolets, which she appeared to confound with mail-coaches or stage-wagons, inasmuch as she was constantly endeavouring for the first half-mile to force her luggage through the little front window, and clamouring to the driver to "put it in the boot." When she was disabused of this idea, her whole being resolved itself into an absorbing anxiety about her pattens, with which she played innumerable games at quoits on Mr. Pecksniff’s legs. It was not until they were close upon the house of mourning that she had enough composure to observe —

"And so the gentleman’s dead, sir! Ah! The more’s the pity." She didn’t even know his name. "But it’s what we must all come to. It’s as certain as being born, except that we can’t make our calculations as exact. Ah! Poor dear!" — Sairey Gamp to Seth Pecksniff, Chapter XIX (August 1843).

By sheer accident, perhaps, and as a consequence of Anthony Chuzzlewit's death and Chuffey's illness, in the eighth monthly instalment Charles Dickens created yet another enduring personage for the cast of The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. In the Phiz plate for that number, Mrs. Sarah Gamp, the lying-in/laying-out nurse and midwife, is looking out of a window above Pol Sweedlepipe's barber and bird-fancier's shop in Mr. Pecksniff on his Mission, complementing the disembodied voice that addresses Seth Pecksniff from above. As a testament to her longevity as a fascinating comic personage, Nicolas Bentley et al. devote over two pages to her in The Dickens Index (1990). Mrs. Gamp, the editors note, "is always armed with 'a species of gig umbrella' from which we derive the slang word 'gamp' for this article" (99). But, more than the incarnation of her mouldy umbrella, she is a distinctive voice that combines the Victorian Cockney accent with the slurred speech of an inebriate.

A Three-quarter century of Mrs. Gamp: Left: Mrs. Gamp (1910) by Harry Furniss. Middle: Mrs. Gamp, on the Art of Nursing (1872) by Fred Barnard. Right: Mrs. Gamp (1843) by Phiz. Click on images to enlarge them.

The Genesis of the Divine Sairey

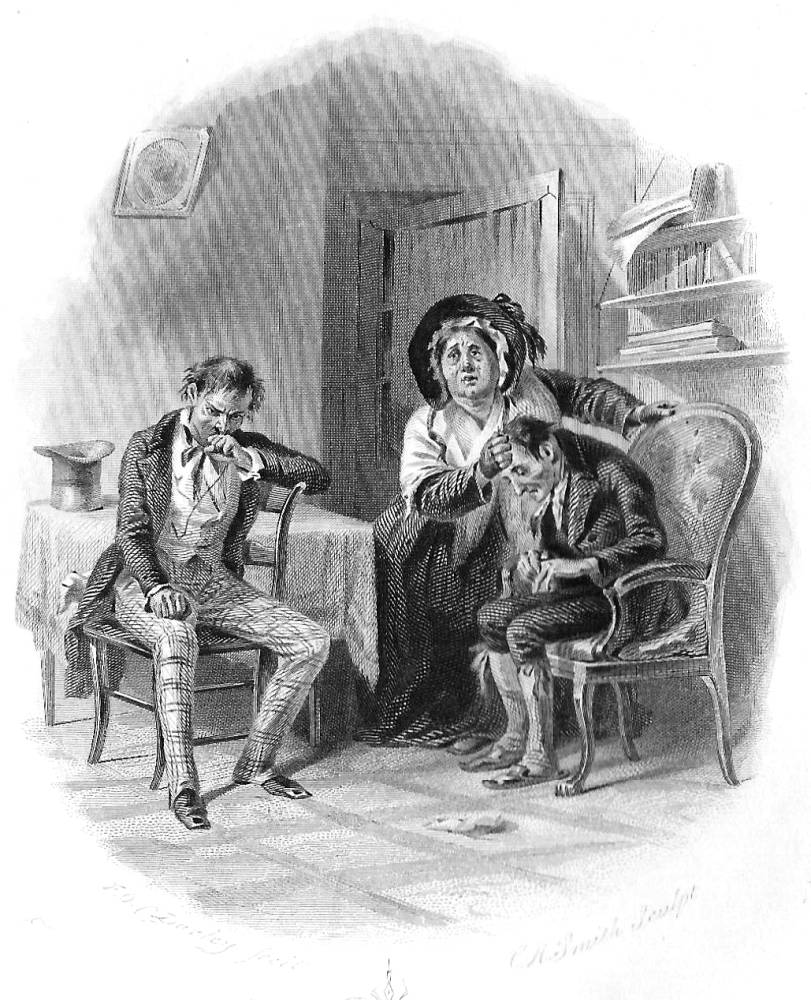

Phiz's Mrs. Gamp has her Eye on the Future, although somewhat cluttered as a design, effectively introduces the novel's chief comic character, Sairey Gamp. Although Dickens may not have seen Honoré Daumier's La Garde-Malade in the 22 May 1842 issue of the Paris magazine of topical commentary and humour Le Charivari, Phiz almost certainly had, for the decrepit image of the French sick-room nurse bears a strong resemblance to the various Phiz illustrations involving Sairey Gamp. Dickens's inspiration, contends Goldie Morgentaler, lay closer to home. According to Michael Slater, Angela Burdette Coutts introduced Dickens to the original of Mrs. Sarah Gamp through her anecdotes "about an eccentric monthly nurse she had recently hired to nurse her companion Hannah Brown" (216), but we must credit Phiz with the development of the iconic image that later illustrators continued to honour. She and, to a lesser extent, Mrs. Nickleby, endure, in spite of post-modernist re-interpretations, "gloriously absurd in their distinct femaleness" (Dickens and Women, 240).

The character was inspired by the nurse of a friend of Angela Burnett Coutts, who had a habit of running her nose along the fender. Dickens confers the same habit on Mrs. Gamp (see ch. 25). At a time when home nursing was the rule, Dickens's portrayal of the snuff-taking, cucumber-loving, gin-swilling, money-grubbing, callous Sarah Gamp gave home nurses a bad name, and, Anne Summers suggests, contributed to the masculinization of the medical profession. [Morgentaler, 355]

Although Dickens introduces Mrs. Gamp as a "professional person" in her female bastion above Poll Sweedlepipe's shop in Chapter XIX, "The Reader is brought into Communication with some Professional Persons, and sheds a Tear over the filial Piety of good Mr. Jonas," in the eighth instalment (August 1843), Phiz does not introduce her in full form until Chapter XXVI, in the tenth monthly number (October 1843). Consequently, one may conclude that Phiz had employed those intervening months in order to collect his thoughts about this physically distinctive character with the unmistakable voice. He probably enquired of the author as to whether she would be a minor character, or would play a more significant role in the plot. In fact, she proves something of a touchstone, connecting characters as various as Nadgett (her landlord), Old Chuffey and Lewsome (her medical charges), Jonas Chuzzlewit (an employer), and ulimately John Westlock.

Phiz's interpretation of Sairey's having "an eye to the future" in the introductory plate's title encompasses both Merry and Sairey, for, as she presents her midwife's card, the young Mrs. Chuzzlewit seems to appeal to the reader for sympathy. Phiz depicts the androgynous nurse with the exaggerated, alcoholic nose and Cockney idiolect holding a candle on one hand (signifying her watching at the patient's bedside) and a business-card in the other, suggestive of her assumption of professional and quasi-male status. She is no "lady," for business is never far from her thoughts:

She was a fat old woman, this Mrs Gamp, with a husky voice and a moist eye, which she had a remarkable power of turning up, and only showing the white of it. Having very little neck, it cost her some trouble to look over herself, if one may say so, at those to whom she talked. She wore a very rusty black gown, rather the worse for snuff, and a shawl and bonnet to correspond. In these dilapidated articles of dress she had, on principle, arrayed herself, time out of mind, on such occasions as the present; for this at once expressed a decent amount of veneration for the deceased, and invited the next of kin to present her with a fresher suit of weeds; an appeal so frequently successful, that the very fetch and ghost of Mrs. Gamp, bonnet and all, might be seen hanging up, any hour in the day, in at least a dozen of the second-hand clothes shops about Holborn. The face of Mrs. Gamp — the nose in particular — was somewhat red and swollen, and it was difficult to enjoy her society without becoming conscious of a smell of spirits. Like most persons who have attained to great eminence in their profession, she took to hers very kindly; insomuch that, setting aside her natural predilections as a woman, she went to a lying-in or a laying-out with equal zest and relish. [Chapter XIX, "The Reader is brought into Communication with some Professional Persons, and sheds a Tear over the filial Piety of good Mr. Jonas," page 236]

Goldie Morgentaler argues that Dickens's comic portrayal of Mrs. Gamp contributes to the novel's selectively misogynistic stance. Whereas Dickens praises Mary Graham for her spiritual, submissive, and sympathetic nature, he ridicules Chariy Pecksniff as a mean-spirited shrew, and has a tendency to caricature older women such as Mrs. Gamp. He consistently describes the novel's young heroines, Mary Graham and Ruth Pinch, in "overly reverential" (p. 356) language, but is highly contemptuous of Sairey Gamp's manner, person, and motivations. The cause of Dickens's negative attitude towards Mrs. Gamp, contends Morgentaler, lies in her financial and vocational independence. In other words, because she earns a living by a quasi-professional practice, she has somehow revolted against male hegemony, and defers to no male authority figure (conveniently, her husband is dead). Morgentaler cites the interpretation of Anne Summers that Dickens is critical about Sarah Gamp's being paid for medical expertise (dubious though it may be), but he does not "vilify the doctors for exactly the same pecuniary interest" (Summers, p. 385). Like the mortician and her professional associate, Mr. Mould, Mrs. Gamp makes a living from the afflictions of her patients. Sarah Gamp and Betsey Prig as sick-room attendants and mid-wives "make a living from disease and death" (Morgentaler, p. 355), and this exploitation of the old, the ill, and the suffering renders them objectionable in Dickens's eyes, perhaps even ghoulish, and therefore fit subjects for withering satire. Coarsened by engaging in work outside the home and given something of a masculine visage from excessive drinking, Sarah Gamp in Phiz's illustrations possesses an overblown, unhealthy female body because she is something of an aberration, an unwomanly woman.

In Dickens and Women (1983), however, Michael Slater's assessment of the lying-in/laying out nurse tends more towards the archetypal than the feminist. She is, he contends, a species of the Femme Fatale, a perversion of the natural feminine predilections such as "gentleness, sympathy, self-sacrificing devotion to the care of the sick" (225). He sums her up as the embodiment of male anxieties about the unknown and unknowable aspects of the female mind and body. She is

a clear literary expression of dread of the female. She is, in her 'highest walk of art', a midwife, also 'a nurse, and watcher, and performer of nameless offices about the persons of the dead'. Her ample form presides, with tipsy gusto, over the great twin mysteries of our existence, birth and death, nd she overflows with arcane female wisdom on these matters, a wisdom dauntingly inaccessible to men. [224]

Significantly, Mrs. Gamp has become a widow without ever becoming a mother. Dickens's inability in the 1840s to dramatize motherliness may be, Slater speculates, "the result of his ever-sharp remembrance of maternal 'betrayal' in childhood" (365) when his mother felt that he should remain at Warren's blacking warehouse rather than return to the family and continue with his schooling. This recollection, or residual feeling, however, Slater contends was gradually "overlain (though far from buried) by more recent, and happier, observation of woman as mother — Catherine Dickens had had six children by the end of 1845" (365). Mrs. Gamp, then, has little in common with such doltish maternal figures as Mrs. Nickleby or Mrs. Gradgrind; she cannot be characterised as "Motherhood in extremis" (365) because she is for the ventriloqual Dickens a mask, persona, or comic voice he may readily assume to entertain a reader or an audience. Like Quilp, she was a grotesque that Dickens adored.

The present-day feminist interpretation of Mrs. Gamp foregrounds issues that Dickens was probably little aware of, namely the economic victimization of women. However, he certainly addresses the industrialist's callous treatment of the middle-class governess, Ruth Pinch, another woman trying to make her way in a male-dominated society. Morgentaler ascribes Dickens's treating Mary Graham and Ruth Pinch with sympathy to their being suitably subservient to men. However, as members of Dickens's own social rank — the class of clerks and civil servants to which his father belonged and to which he seemed destined — they constitute sentient beings, not merely workhorses in skirts, which seems to be his attitude towards Sairey Gamp and Betsey Prig. In other words, he has adjusted his approach to his female characters according to their class, an attitude that many of his English middle-class readers would have shared. Consequently, even late into the nineteenth century, when education was levelling the differences between the classes and middle-class women such as Mary and Ruth had other vocational options such as nursing and teaching (neither of which would have been considered socially appropriate in the 1840s), readers of both sexes could love Sairey Gamp as a quaint Dickens "original" without being perpetrators or facilitators of the male oppression of women. For Dickens and for many of his readers still, Sairey Gamp does not function as a fully developed character, despite her tendency towards philosophizing about the vagaries of life, but rather as an endearing rascal — a unidimensional caricature whose appeals to the authoritative judgment of the imaginary Mrs. Harris ("'arris") are as hilarious as her grammatical solecisms, continual mispronunciations, and egregious malapropisms:

"I think, young woman," said Mrs Gamp to the assistant chambermaid, in a tone expressive of weakness, "that I could pick a little bit of pickled salmon, with a nice little sprig of fennel, and a sprinkling of white pepper. I takes new bread, my dear, with just a little pat of fresh butter, and a mossel of cheese. In case there should be such a thing as a cowcumber in the ‘ouse, will you be so kind as bring it, for I’m rather partial to ‘em, and they does a world of good in a sick room. If they draws the Brighton Old Tipper here, I takes that ale at night, my love, it bein’ considered wakeful by the doctors. And whatever you do, young woman, don’t bring more than a shilling’s-worth of gin and water-warm when I rings the bell a second time; for that is always my allowance, and I never takes a drop beyond!’" [Sairey Gamp to Jonas's chambermaid, Chapter XXV: October 1843]

Epilogue: Sairey Resurgens

In Dickens, Slater notes that Sairey Gamp, twenty-five years after her initial appearance in print, enjoyed a considerable after-life in the United States of America. In the ninth week of Dickens's 1867 American reading tour, Dickens introduced The Poor Traveller, Boots at the Holly-tree Inn and Mrs Gamp to his platform program. Apparently, in the Boots and the last of the three pieces, Dickens exercised "strong ventriloquial effects, using two of his most popular characters to date" (463), who both speak with markedly Cockney accents, and would therefore present thoroughly English types to his American audiences.

Relevant Sairey Gamp illustrations from various editions, 1843 to 1910

Left: Phiz's original conception of Sairey Gamp interacting with Merry to the narrative-pictorial series: Mrs. Gamp has her Eye on the Future (October 1843). Centre: Kyd's miniature portrait of Mrs. Gamp walking through the streets with hat, bag, and umbrella, Sairey Gamp (card no. 24, 1910). Right: From Kyd's book of remarkable Dickens characters, Sairey Gamp in watercolour, as seen in Ch. 19.

Left: Harry Furniss's study of the great comic creation for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910), Sairey Gamp. Centre: F. O. C. Darley's frontispiece for volume two, "The creetur's head's so hot," said Mrs. Gamp, alluding to her attendance on the old clerk, Chuffey (1863). Right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Sairey Gamp and Betsey Prig. (1867). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Fred Barnard's Mrs. Gamp favours the company with an exhibition of professional skill, old Chuffey being the object of her ministrations in Chapter 46 of the Household Edition (1872).

Related Materials: Other Illustrations

- Daumier's The Sickroom Nurse (La Garde-Malade) (22 May 1842)

- Illustrations by Sol Eytinge, Jr. (16 plates from the Ticknor and Fields' Diamond Edition of 1867)

- Fred Barnard (60 plates from the Chapman and Hall Household Edition of 1872)

- Clayton J. Clarke (five studies from three sources, 1910)

- Harry Furniss (twenty-eight lithographs for the Charles Dickens Library Edition, 1910)

References

Baillie, Joanna. "Woo'd and Married and a'." Women Poets of the Nineteenth Century. Ed. Alfred H. Miles. George Routledge & Sons; New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1907. 2 vols.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slaster, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1844.

_____. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872.

_____. Martin Chuzzlewit. Edited by Andrew Lang and illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. The Works of Charles Dickens in Thirty-four Volumes, vol. III. The Gadshill Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1897. 2 vols.

Guerard, Albert J. "Martin Chuzzlewit: The Novel as Comic Entertainment." The Triumph of the Novel: Dickens, Dostoevsky, Faulkner. Chicago & London: U. Chicago P., 1976. Pp. 235-260.

Hammerton, J. A. Ch. 15, "Martin Chuzzlewit." The Dickens Picture-Book: A Record of the Dickens Illustrations with 600 Illustrations and a Frontispiece by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Pp. 266-293.

Harvey, John R. Ch. 6, "Dickens and Browne: Martin Chuzzledwit to Bleak House." Victorian Novelists and Their Illustrators. London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1970.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Morgentaler, Goldie. Chapter 24. "Martin Chuzzlewit. A Companion to Charles Dickens, ed. David Paroissien. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. Pp. 348-357.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens. London and New Haven: Yale U. P., 2009.

_____. "II. The Women of the Novels. Chapter 11, Sketches by Boz to Martin Chuzzlewit." London: J. M. Dent, 1983. Pp. 221-242.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington and London: Indiana U. P., 1978.

_____. "Martin Chuzzlewit's Progress by Dickens and Phiz." Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972): 119-149.

Summers, Anne. "The Mysterious Demise of Sarah Gamp: The Domiciliary Nurse and her Detractors, c. 1830-1860." Victorian Studies, 32: 365-86.

Vann, J. Don. "Martin Chuzzlewit, twenty parts in nineteen monthly installments, January 1843 — July 1844." New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 66-67.

Last modified 23 March 2019