ir Edward G. D. Bulwer-Lytton, the youngest of the three sons of General William Earle Bulwer (1757-1807) of Heydon Hall in Norfolk and the Herfordshire heiress Elizabeth Barbara Lytton (1773-1843) of the Robinson and Lytton families of Knebworth, was born at 31 Baker Str., London, on 25 May, 1803. Within a year, Mrs. Bulwer sought legal guardianship of her children through the Court of Chancery owing to her husband's volcanic temperament. The British government, in anticipation of a Napoleonic invasion, at that time appointed General Bulwer military commander of Lancashire to arrange for that county's defence. However, on 7 July, 1807, General Bulwer, died before he could be elevated to the peerage in recognition for his service to his country. In 1812, the widow sent Edward to Dr. Ruddock's school in Fulham, but, as a result of ill-treatment there, she transferred him to Dr. Hooker's school at Rottingdean. Despite his precocity and early love of books, inherited from his mother, he was not accomplishing anything academically, and his mother was concerned that he would be ill-prepared for university.

ir Edward G. D. Bulwer-Lytton, the youngest of the three sons of General William Earle Bulwer (1757-1807) of Heydon Hall in Norfolk and the Herfordshire heiress Elizabeth Barbara Lytton (1773-1843) of the Robinson and Lytton families of Knebworth, was born at 31 Baker Str., London, on 25 May, 1803. Within a year, Mrs. Bulwer sought legal guardianship of her children through the Court of Chancery owing to her husband's volcanic temperament. The British government, in anticipation of a Napoleonic invasion, at that time appointed General Bulwer military commander of Lancashire to arrange for that county's defence. However, on 7 July, 1807, General Bulwer, died before he could be elevated to the peerage in recognition for his service to his country. In 1812, the widow sent Edward to Dr. Ruddock's school in Fulham, but, as a result of ill-treatment there, she transferred him to Dr. Hooker's school at Rottingdean. Despite his precocity and early love of books, inherited from his mother, he was not accomplishing anything academically, and his mother was concerned that he would be ill-prepared for university.

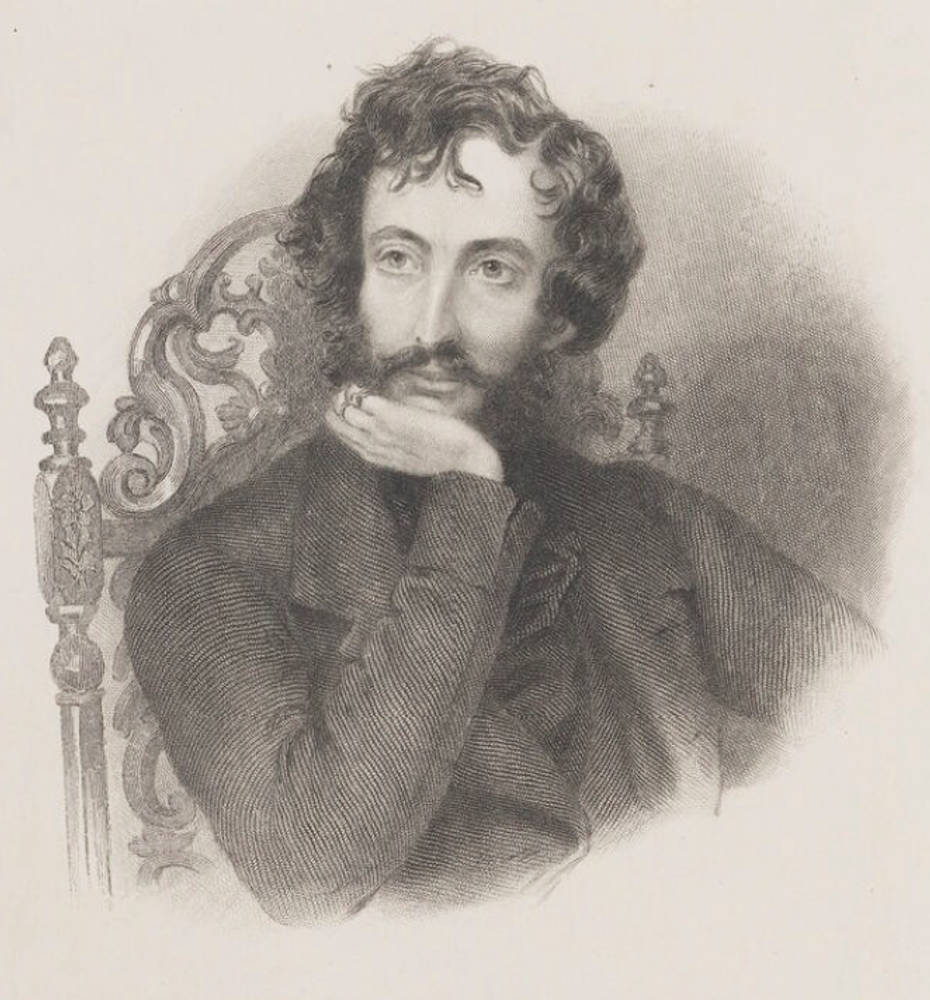

Henry William Pickersgill’s c.1831 painting of the young writer.

In the summer, 1820, while Bulwer was studying Latin, Greek, history, and rhetoric under Rev. Charles Wallington at Ealing in preparation for attending Cambridge, he fell deeply in love with a girl known to others only as "Lucy D — -." Before the relationship could develop from the platonic stage, "the mysterious girl suddenly disappeared one day — removed by her father and harried into a ruinous marriage" (Christensen 4), driving young Edward into a Byronic melancholy. Three years later, the girl wrote Bulwer that she was still in love with him — and dying. She summoned him to her graveside in the Lake District, and, in 1833, while traveling through England and abroad, he made a pilgrimage to her grave in Ullswater. The experience apparently brought him out of his melancholia. Subsequently, while staying at Knebworth, he had a brief affair with Lord Byron's ex-mistress, Lady Caroline Lamb which "led indirectly to the life-long torture of his marriage to her protégée, Rosina Wheeler" (Christensen 5).

In 1820, at his mother's instigation, the London firm of J. Hatchard and Son published the Byronic Ismael: An Oriental Tale, with Other Poems, for which, even though sales were poor, young Edward received acknowledgement from Sir Walter Scott. The following year, Edward honed his mathematics skills under the tutelage of an Oxford scholar named Thomson, and in 1822 entered Trinity College, Cambridge, during the Easter term, transferring to Trinity Hall as a fellow-commoner in order to be excused from attending lectures. Through the Union Debating Society he became acquainted with the university's leading undergraduates, including the future historian Thomas Babington Macaulay, Alexander Cockburn (later, a chief justice), W. M. Praed, Charles Villiers, F. D. Maurice, Charles Buller, and Benjamin Hall Kennedy, who years later would piece together Bulwer's novel from his extant notes. While still at Cambridge, still working in the Byronic mode, he published Delmour; or, A Tale of a Sylphid, and Other Poems. In July, 1825, he was awarded the Chancellor's medal for his English poem "Sculpture," which when published was immediately attacked William Makepeace Thackeray in Fraser's Magazine, initiating a lifetime's literary antipathy during which Thackeray dubbed Bulwer the novelist "a silver fork polisher," the term "silver fork" describing the species of high society novel that was much in vogue throughout the century. At this time he also wrote a large part of an unpublished novel, Rupert de Lindsay, and the poetry collectionWeeds and Wildflowers (1826). Taking his his B.A., young Edward travelled to Paris, becoming acquainted with the Marquise de la Rochejacquele and her two daughters in the Faubourg St. Germain. After a dalliance with a well-born Parisian girl which his mother, very much an anti-Catholic, broke off, Edward withdrew to the woods around Versailles, riding and writing verse. Returning to London in April, he quickly shook off his despondency by throwing himself into fashionable society.

Left: Edward George Earle Lytton Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton. G. Cook after Richard James Lane. 1848. Right: Rosina Anne Doyle Bulwer-Lytton (née Wheeler), Lady Lytton (1802-1882). Engraving by John Jewell Penstone after Alfred Edward Chalon. 1852. Both courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

At an evening party, he met Rosina Doyle Wheeler, a young Irish woman of wit and beauty, niece of General Sir John Doyle. The mutual attraction was instantaneous, and in August they declared their love. On 30 August, 1827, they married at St. James's, London — much to his mother's displeasure. They spent the next two years in Reading, happy despite the fact that Rosina's income was only £80 per annum and his mother had cut off his allowance. Their first child, Emily, was born at this time. Between 1827 and 1835, their household expenditures amounted to approximately £3000 per year, an extravagant lifestyle that necessitated Bulwer's becoming a prolific writer: during these years, he wrote thirteen novels, two long poems, four plays, a social history of England from the turn of the century, a three-volume history of Athens, the tales collected in The Student (1835); he edited the New Monthly Magazine (1831-2), and published numerous essays anonymously in the Edinburgh Review, the Westminster Review, the Monthly Chronicle, the Examiner, and the Literary Gazette.

His first novel, the gloomy Byronic romance Falkland (1827) failed to excite public interest, but Pelham; or, The Adventures of a Gentleman (1828), a 'Silver Fork' novel of manners and fashionable life inaugurated his career as a fluent, popular novelist. The hero's mother, Lady Frances, who possesses a sophisticated, witty letter-writing style based on that of Lord Chesterfield, helped to set a new fashion in evening wear, for in the novel she favours Black as opposed to the then-popular Blue. InThe Disowned (Dec., 1828) the young novelist drew upon his own youthful experiences with the Gypsies near his mother's estates and his sojourn in France. His fourth novel, Devereux(1829), set during the reign of Queen Anne, was his first (unsuccessful) attempt at the genre of the historical novel. In August, 1830, he published his first Newgate (crime) novel, Paul Clifford, the beginning of his 'novels with a purpose', the cause in this case being judicial reform. On 8 November, 1831, Bulwer's son Robert was born; he would later become a highly successful career diplomat and accomplished poet. Bulwer's 1832 historically-based psychological crime thriller Eugene Aram raised a storm of protest because he had made a murderer (a self-educated scholar) his hero. In 1833, he published Godolphin, a novel which is his first to embody an occult theme. This large output of work, which included poems such as The Siamese Twins (1831) as well as novels, strained the Bulwers' marriage. Despite the success of The Last Days of Pompeii (1834), Bulwer could not cease from his labours; he was often irritable and neglected his family. After many violent quarrels, he and Rosina legally separated in 1836. She continued to plague him for the rest of his life, and indeed outlived him.

The trip to Italy with Rosina in 1833-34 was the end of the marriage idyll, but that experience combined with Bulwer's considerable reading of mediaeval and classical history bore fruit not only in his 1834 sensation novel about the volcanic destruction of the infamous Roman pleasure resort in August, 79 A.D., but also in the three-volume novel Rienzi; or, The Last of the Roman Tribunes (1835), set in mediaeval Italy, and his two-volume study Athens, Its Rise and Fall (1837). The five years immediately following his legal separation from Rosina in April, 1836, saw Bulwer writing not only verse and prose, but also verse drama. Meantime, he continued to write novels skillfully blending metaphysics with his autobiographical observations about contemporary high society — Ernest Maltravers (1837) and its companion, Alice; or, The Mysteries(1838), Night and Morning (1841), and Zanoni (1842 — all in the triple-decker format favoured by the lending libraries.

In addition to his writing and traveling, Bulwer-Lytton had a successful political career, serving twice in Parliament — first as a Whig Radical for eleven years from 1831 and then, after an eleven year hiatus, as a Conservative MP from 1852 to 1866, when he entered the House of Lords.

Alexander Bassono’s photograph of Bulwer-Lytton's son, (Edward) Robert Lytton Bulwer-Lytton (1831-91), who became the first Viceroy of India. He was also a poet, under the pen-name Owen Meredith.

By nature diffident and reserved, Bulwer-Lytton's increasing deafness only served to keep him more and more out of the public eye. He lived alone at Knebworth part of the year, spending the rest on the continent, taking the spa waters to bolster his declining health. He found attending to the debates in the House of Lords difficult, although he tried his best to follow the arguments pro and con over the Second Reform Bill (1867). Honours continued to be showered upon him: the Order and St. Michael and St. George (15 January, 1870), an honorary LL.D. from Oxford (1864), the rectorship of Glasgow University (1856, 1856), and even an offer of the throne of Greece, left vacant by the abdication of King Otho. During the late fall of 1872, his son Robert and his daughter-in-law having returned from a diplomatic posting abroad, they stayed with Bulwer-Lytton at Torquay. When they departed on 4 January, 1873, he began to complain of excruciating pains and horrendous noises in both ears; a few days later, he went blind. On the night on January 17th he suffered epileptic seizures, dying in his sleep the following day, a victim of the ear infection that had plagued him for years and had finally reached his brain. On 25 January, he was buried in St. Edmund's Chapel, near Poets' Corner, in Westminster Abbey.

*Many thanks to Dr. Michael Riley, for making some corrections to this page.

Related Materials

- A Brief Introduction

- Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s committal of his wife Rosina to a private mental asylum in 1858

- Edward Bulwer-Lytton and Charles Dickens

- Edward Bulwer-Lytton: Whig Radical and Progressive Conservative

- Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Successful Dramatist

- Bulwer-Lytton's Legacy

- A Bulwer-Lytton Chronology

- G. F. Watts's portrait of Robert Bulwer-Lytton (Lord Lytton)

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Booth, Michael R. "I. The Social and literary context." The Revels History of Drama in English, eds. Clifford Leech and T. W. Craik. London: Methuen, 1975.

"Bulwer-Lytton." http://lang.nagoya-u.ac.ip/~matsuoka/Bulwer-Lytton.html

Campbell, James L. Sr. Edward Bulwer-Lytton. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1986.

Christensen, Allan C. Edward Bulwer-Lytton: The Fiction of New Regions. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1976.

Dahl, Curtis. "Bulwer-Lytton." Victorian Fiction: A Second Guide to Research, ed. George H. Ford. New York: Modern Language Association, 1978. Pp. 28-33.

Grosvenor Myer, Valerie. "Bulwer-Lytton, Edward George Earle Lytton, First Lord Lytton (1803-1873)." Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York: Garland, 1988. Page 103.

Kaplan, Fred. Dickens: A Biography. New York: William Morrow, 1988.

Ley, J. W. T. The Dickens Circle. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1918.

"Lytton (of Knebworth), Edward George Earle Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron." Encyclopaedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/bcom/eb/article/7/0,5716,50757+1,00.html

Last updated 14 June 2022