Click on the images to enlarge them, and sometimes for more information about them.

Thomas Willement, © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Thomas Willement has an important place in the history of Gothic Revival stained glass, because his work spanned the early manifestations of the revival in the late Georgian period and its full-blown flowering in Victorian times: he was Heraldic Artist to George IV and then Artist in Stained Glass to Queen Victoria. Indeed, he is widely considered "the father of Victorian stained glass" (National Trust, 319). He had the distinction of being the first glassmaker to be commissioned by A. W. N. Pugin (see Hill 229) — even if Pugin got so tired of his early glassmakers (and the prices they charged) that he turned to John Hardman instead.

In particular, Willement exemplifies the connection between stained glass and heraldry. His father was a "coach, herald, and house painter and artist to his royal highness the duke of York" (Shepherd) and it is more than likely that his career started in his father's business off Grosvenor Square. His early work was generally heraldic in nature, and he wrote about the subject as well, becoming a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1832 (Shepherd). His royal connections brought major commissions: among the places he worked on were the dazzling interior of St George's Chapel at Windsor and the no less dazzling Great Hall of Hampton Court Palace, both with architect Edward Blore. The work at Windsor was very extensive, lasting from 1840-1861 (see Shepherd). These commissions were by no means confined to stained glass. Here is the Ecclesiologist commenting approvingly on one part of his work at Windsor: "Heraldry is well adapted for emblazonment upon organ pipes. Few specimens are more satisfactory than the diapasons of the great organ at S. George's chapel, Windsor, which display the royal arms and supporters very happily grouped. These are the work of Mr. Willement" (378).

Willement's work up to 1840 is fully documented in his own Concise Account of the Principal Works in Stained Glass executed by him up to that time. Then in the early 1840s he worked on two notable restorations, that of the Temple Church in the Inns of Court, and the Round Church (or Church of the Holy Sepulchre) in Cambridge. Not much of his stained glass remains to be seen in these churches. For example, the east window of the Round Church had to be replaced after the Second World War. But he was bound to go on responding to the great boom in church building and restoration, and although he also "made furniture, designed metalwork, executed decorative painting and worked with textiles and ceramics," most of the work listed in another set of records, a database at the Victoria and Albert Museum, was in stained glass: "Of the 1,671 records in the database, 1,228, or 73 per cent, were stained-glass jobs" (Cheshire 37).

Left: The Great Hall at Hampton Court (Source: Knight, facing p.14). Right: The West Front of the Church and Priory at Davington in 1850 (Source: Willement IV, p. 37).

With the sharp rise in demand for such jobs (see Cheshire 38), Willement was able to commit himself to a costly project of his own. In 1845, he moved to Faversham in Kent, where he had bought Davington Priory, with its medieval origins (now owned by the singer and activist Bob Geldof). His work on that, which included an illustrated book in which he briefly outlines the improvements so far (see pp. 39-42), was a major enterprise in the following years. At this time too he was engaged in work at York Minster, Wells Cathedral and elsewhere, including St Luke's, Chelsea.

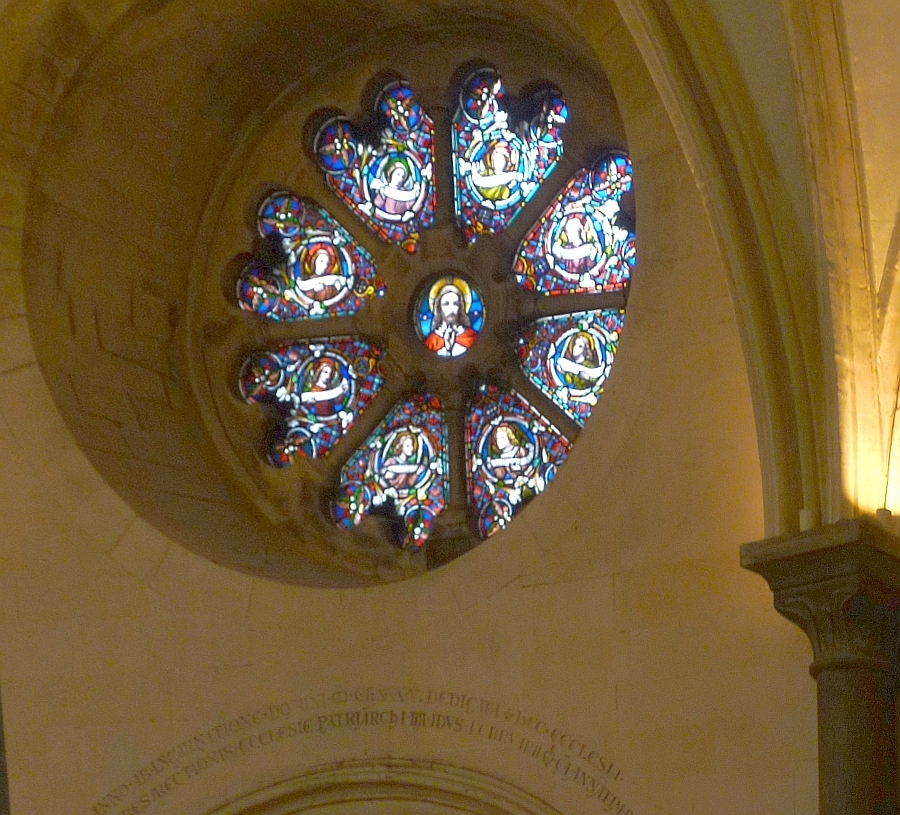

Willement's roundel in the nave of Temple Church,

showing Christ surrounded by his angels. (c)

As time went by, heraldic glass, which was Willement's abiding interest and greatest strength, was less in demand than glass depicting Biblical figures and episodes. His general approach, too, became unfashionable. He believed in reproducing the work of medieval glaziers as closely as possible: "Willement adopted an imitative approach, looking to create medieval effects by reproducing directly from ancient models or their likenesses" (Shepherd). This was something he seems to have passed on to two of the stained glass designers known to have spent some time in his office during their early careers — William Warrington and Michael O'Connor, although the latter was praised for his figure painting as well. Taste in stained glass moved on; yet Willement, with his important connections and commissions, together with the high reputation of his studio and his scholarly writings, remains a pioneering figure. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Willement's motto, appearing at the

end of his 1840 list of works (p.75)

Stained Glass

- Rose window (and decorative work) in the Temple Church, London

- East window of Library, Ripon Cathedral (probable contributions)

- Grantley Memorial Window, Ripon Cathedral

- East Window, Lady Chapel, Wells Cathedral (restoration)

Other Work

Bibliography

Allen, John. "Architects and Artists WXYZ." Sussex Parish Churches. Web. 5 September 2021.

Brown, Sarah. "So Perfectly Satisfactory: The Stained Glass of Thomas Willement." In A History of the Stained Glass of St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle. Historical Monographs Relating to St George’s Chapel, Vol. 18. Windsor, 2006. 109–45.

Cheshire, Jim. Stained Glass and the Victorian Gothic Revival. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004.

The Ecclesiologist. Vol. X (New Series, Vol. VII). Google Books (free book). Web. 5 September 2021.

Hill, Rosemary. God's Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2008.

Knight, Charles. Old England: A Pictorial Museum, Regal, Ecclesiastical, Municipal, Baronial and Popular Antiquities. London: James Sangster & Co, 1850. Internet Archive. Contributed by Harvard University. Web. 5 September 2021.

National Trust. Treasures of the National Trust. London: National Trust Books, 2007.

Shepherd, Stanley A. "Willement, Thomas (1786–1871), writer on heraldry and stained-glass artist." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 4 September 2021.

Willement, Thomas. Concise Account of the Principal Works in Stained Glass that Have Been Executed by Thomas Willement. Hathi Trust. Contributed by the University of California. Web. 5 September 2021.

_____. Davington Parish and the Priory of S. Mary Magdalene, Kent. London: Pickering, 1862. Hathi Trust. Contributed by Harvard University. Web. 5 September 2021.

Created 5 September 2021