Stephen Adam was a major Figure in the field of nineteenth-century Scottish stained glass. The many windows from his studio in buildings throughout Scotland and beyond form part of his lasting legacy in this art form. Adam made a profound impression upon younger artists, some of whom received their training in his studio and, in Late Romantic fashion, his work is a bridge spanning the closing decades of the nineteenth century and the opening years of the twentieth century. Stephen Adam is a stained glass artist well worth study beyond the scope of this profile.

Born in 1848 and a native of Edinburgh, Adam was educated there at the Cannonmills school where the Scottish writer, Robert Louis Stevenson was his contemporary.1 From an early age Adam showed evidence of great talent in drawing and painting and thus came to the attention of Edinburgh’s leading stained glass artist, James Ballantine, a noted talent spotter. Adam became an apprentice in Ballantine’s studio, where his early training laid the basis of his future progress as a stained glass artist (obituary). When his apprenticeship was concluded in 1867 he moved with his parents to Glasgow where he was a student of the Haldane Academy (later to become Glasgow School of Art). His abilities in design won him a medal and an apprenticeship with the successful Scottish stained glass artist Daniel Cottier, who would have a considerable impact on Adam, helping him to form his distinctive style, as he later acknowledged.

These were the powerful influences working upon the young Adam: the experienced Ballantine, a ‘Renaissance man’ who once had been slab boy to the great Scottish artist David Roberts; and Daniel Cottier, design pioneer and innovator, who introduced the Aesthetic Movement to America. Adam elucidated further in his lecture ‘Truth in Decorative Art: Ecclesiastical Glass Staining’, delivered in Glasgow in 1895: ‘In design I have been greatly influenced by the works of Rossetti, Burne-Jones, William Morris and Puvis de Chavannes; and if I may sp eak confidently of my work as a colourist, I found my master in the late Daniel Cottier, the eminent glass painter’.2

Stephen Adam established his own studio at 121 Bath Street, Glasgow in 1870 and for the next four decades produced a prolific series of windows, fulfilling a full range of ecclesiastical, civic and domestic commissions and encompassing a wide variety of themes, as his catalogue for 1902 illustrates.3 He employed a series of gifted freelance artists to design for the studio, including Robert Burns, David Gauld, and Alex Walker, and was later joined by his son, Stephen Adam Junior, and the brilliant young artist, Alfred Webster, an ill-fated triangle as events would show.

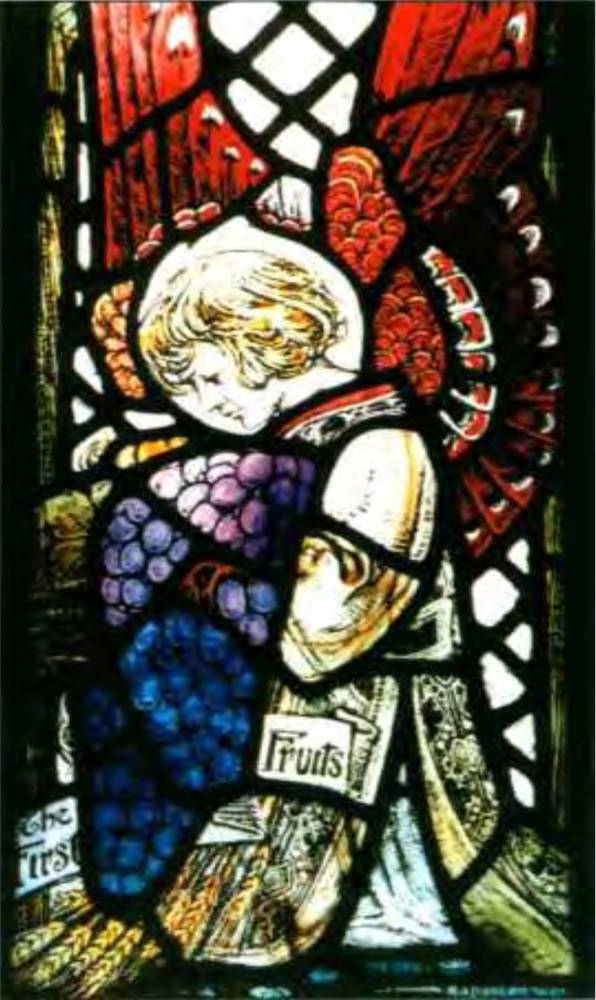

Fruits and foliage panel. From gallery window (1877), former Belhaven Church, Glasgow.

Adam’s own style became more personal and distinctive, moving through progressive, chronological stages to reach its apogee in a series of great windows in the closing years of the nineteenth century and opening years of the next. Truly he had mastered his art. He believed that good drawing did not consist of ‘elaborate rendering or drapery, but rather a certain external form and balancing of parts as evidenced in the Flaxman cartoons and in the classic frescoes’.4 The slavish copying of early works he denounced as anachronistic and distasteful:

windows and Figures... observe those twisted necks, painfully pathetic faces, the dainty curl, each hair alike, those angular limbs... . And those deformities are manufactured and catalogued principally in London, and the country is overrun with stock saints and evangelists of all sizes, at per foot prices, say a trifle extra if Peter has two keys; Acts of Mercy in which the quality is strained, and so on. True, they revive transparency and discard enamel -- and with it all originality. [Stained Glass — its History and Modern Development]

This savage commentary makes clear that Adam heartily disliked this imitative style with its stipple shading — shading which he found at odds with the medium — and he also had an antipathy for hard or flashed blue which could not look successful placed beside other colours. He was an advocate of the linear approach and as his style matured, so did the spatial forms of his windows expand as a result of his increasingly confident approach to more ambitious forms of iconography. In his final phase he entered into his greatest creative period, employing a wide range of new glasses and a style that was more economical (in terms of ornamentation), and also more dramatic in its colour range, using a dark spectrum of blacks, greys, deep blues and dark browns to add depth and dimension.5 During this period a Japanese sensibility is evident in his work, although his Figure drawing generally reflected a classical, and at times, late Pre-Raphaelite influence.

In his book Adventures in Light and Color6 the American glassman and critic Charles Connick proclaimed Adam as the pioneer of modern stained glass in Scotland and it is Martin Harrison in his book Victorian Stained Glass who sets this precisely in context, showing the line of succession passing from Cottier to Adam, from master to pupil, as it would later pass from Adam to Alfred Webster in 1910:

Cottier had opened branches in New York and Sydney in 1873 and no doubt Connick regarded Cottier as American rather than Scottish, but the significant point here is that Adam became Cottier’s stylistic successor in Scotland and was able to satisfy a demand which Cottier had helped to create but whose absence made it difficult to fulfil. Between 1870-1885 the firm of Adam & Small made the finest stained glass of that period in Scotland, dominated always by Adam’s Figure drawing which owed a little to the Pre-Raphaelites but more to the Neo- Classical. It is no surprise to find Adam, in 1877, advocating as models Burne-Jones, Leighton, Poynter and Albert Moore... who, in different styles show drawing suitable for treatment in glass.7

It is now appropriate to consider some examples of the prolific output of Stephen Adam’s studio, examining the windows within their architectural context, but not in any chronological order.

Ecclesiastical work

Smollett window (1880), west nave, BonhillParish Church.

In 1878 Adam embarked upon an important commission -- a defining one in the evolution of stained glass in Scotland. For the new Burgh Hall in Maryhill built by Glasgow architect Duncan MacNaughton in the French Renaissance style, Adam designed a complete scheme of windows illustrating the wide range of industries present in that northern area of Glasgow as a result of nineteenth-century industrial expansion. The series of twenty panels (now removed from their original settings and currently in storage)8 form an indigenous set whose subject matter marks a distinct departure from cosmetic, sanitised and idealised Scottish scenery sketched and painted from a distance. Michael Donnelly has succinctly emphasised this critical departure:

In his outstanding series of panels Adam chose to depict the tradesmen not artificially in their best as did so many contemporary photographs, but at labour in their working clothes. The accuracy of detail leaves little doubt that the preliminary sketches for these panels were done in the field years before anyone had heard of the Glasgow Boys, and in the kind of industrial settings that they avoided like the plague.9

Detail from The Baptism of Christ (1907), east nave, Lecropt Kirk, Stirlingshire.

In Scotland, the Maryhill windows thus illustrated the new relationship developing between industry and art — a world away from the pastoral, bucolic scenes with their fashionable classical overtones and inscriptions like Gather Ye Rosebuds While Ye May favoured by wealthy patrons for their town houses and country seats, which ignored completely the dirt and grime of a gr eat industrial city. Adam’s Mary hill windows are also colour studies, executed in a controlled light palette of gre ens, browns, golds and grey s with flashes of deeper colour. This is clearly illustrated in the Railwaymen panel (Fig. 1), where a porter converses with an engine driver (an early illustration of the emergent railway industry whose vast locomotive works were situated in the adjacent St Rollox area), the orange coloured steam floating above the horizontal green bandings of the engine. Also strikingly modern is the device Adam has used -- by depicting the porter from behind we identify with his stance and outlook, placing ourselves in the midst of this scene of industry. In the Boat Builder panel, the dark green jacket and red stock of the builder contrasts effectively with the various shades of wood, some of it elaborately decorated, containing a swan motif. The boat is perhaps a canal barge, being built for trade on the neighbouring Forth & Clyde canal.

Some twenty years later Adam executed a similar series of panels, to adorn the upper fenestration in the sumptuous Boardroom of Glasgow’s Clydeport Authority in the heart of the city.10 Shipbuilding and shipping were the themes for these nautical windows, illustrating a series of working portraits of carpenters, shipwrights, stevedores and welders, all depicted realistically in their various industrial contexts. Here Adam employs a different, sharper palette and there is realism in the heat and flame of the welders’ panels, the crimson flames contrasting with the grey and mauve of the metal.

Within the lofty Normandy Gothic of James Sellars’s Belhaven Church in Glasgow’s prosperous west end (now St Luke’s Greek Orthodox Cathedral),11 there is a series of windows by Adam of 1877, a special feature of which is his use of fruit and foliage motifs. These are beautifully drawn and show the influence of Japanese art, delicate and incisive in muted shades of blue, silver, green and gold, and of William Morris in the willow-patterned background (Fig. 2). These decorative panels function as foils for the subtly-coloured Figure panels, based upon illustrations from the parables and which constitute independent colour studies on their own.

For John Baird’s large and austere Perpendicular Gothic church at Bonhill, Adam designed two large single-light Heritors’ Windows, installed in 1880.12 The Heritors in the Church of Scotland belonged to the landed classes whose responsibility it was to build and maintain the kirks. Thus in the latter half of the nineteenth century numerous Heritors’ Windows were installed. Primarily armigerous windows with no direct religious meaning, their purpose was to exhibit and proclaim status within a parish and community. Adam designed many such windows and his Smollett window in Bonhill is a fine example of the genre. The Smolletts were an old merchant family (from whom came the novelist Tobias Smollett), who had obtained lands and armigerous rights in previous centuries. Their heraldic description reads: Azure a bend or, between a lion rampant holding in his paw a silver banner, and a silver bugle horn, and an Oak Tree Crest (Motto Viresco — I flourish).13 Adam translated this grap hically into the medium of stained glass making use of grisaille qu arry backgrounds with borders of strong Gothic Revival colours and a prominent central dark blue shield containing the Smollett arms. Adam used high quality glass for this window (Fig. 3), which in 1880 cost £103-10-6.14

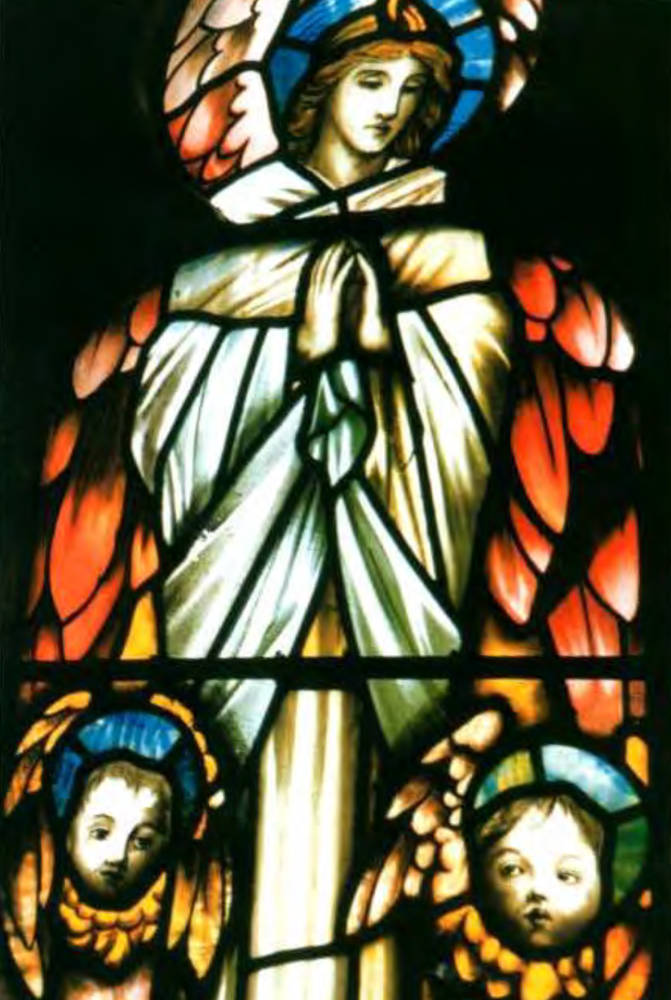

Lecropt Kirk is a handsome essay in perpendicular Gothic Revival built in 1827 and occupying an elevated position above the flat carse lands of Stirlingshire.15 (BSMGP members visited this church during their 2005 Edinburgh Conference). Lecropt’s simple Gothic windows provide excellent settings for stained glass, but the earliest example was installed by Stephen Adam in 1907, towards the close of his last and greatest creative period. The window on the south wall of the chancel has two themes — the Baptism of Christ and the Risen Christ — executed in the strong palette of varied tones and colours of this late phase. Christ at his Baptism is a pale, emphatically drawn Figure in white clothing which is streaked with light green and with veins of lemon and red. The upper lights are studies in crimson, blue and gold, used for the tall angel Figure and the cherubim, whose faces contain an enigmatic, even slightly sinister quality, found elsewhere in Adam’s windows and difficult to interpret (Fig. 4). The mysterious gestalt philosophy of art — the world of Wertheimer, Koffka and Kohler — states that nothing can be added to a work of art, total and complete in itself, where all is waiting to be discovered. A concept perhaps applicable to this strange factor in Adam’s drawing? Above the north door of Lecropt Kirk is the Henderson Memorial window, the result of a dark tragedy where all five children of the late nineteenth-century minister of Lecropt died during their childhood. Deep rich colours are set against a dark background, as five children cluster round their parents. Once again, that strange enigmatic element found m Adam’s latter work is present — evident in the unsettling cherubim and a little golden child with clasped hands at prayer enfolded in his father’s arms, who gazes intently at those who view this window.

Christ with Mary Magdalene. 1908. West nave, Kilmore Church, Isle of Mull.

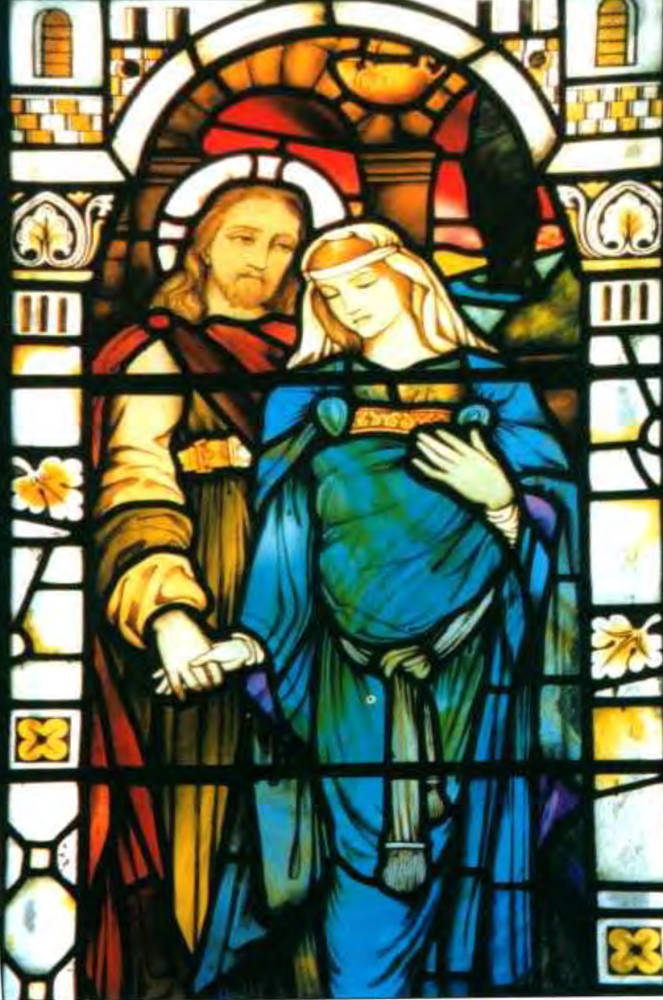

Kilmore Church at Dervaig on the Isle of Mull, is one of architect Peter MacGregor Chalmers’s Celtic round tower churches — a powerful miniature composition high above the estuary of the Bellart,with an arresting Arts & Crafts interior and complete scheme of Stephen Adam windows, also from his final phase.16 That odd, elusive, sometimes disturbing element is present here in the Figures of a female saint with cross and bible, richly attired but with a hostile countenance, and equally in an elongated, luminous Christ with long, tapering fingers who appears out of the storm to his frightened disciples. In another window (Fig. 5) Mary Magdalene appears to be pregnant and holds the hand of a sad Christ, the downcast couple close in physical intimacy (recalling whispers of an ancient heresy that the bloodline of Christ may have continued through this liaison). The bold choice of colour and sheer quality of the glass used for her robes make an even stronger impression framed in Adam’s unusually simplified and modern interp retation of architectural canopywork.

In another in the series, Christ the Good Shepherd is a more traditional figure, set under vine canopies, suggesting an awareness of the Christopher Whall’s hallmark use of natural forms for canopies.The windows were all installed within a five-year span (1905-1910) as memorials to landed gentry whose est at es lay within this extensive parish — Mornish, Torloisk, Glengorm, Ardow — and the hand of Adam’s brilliant assistant, Alfred Webs t er is evident in some aspects of the iconography of this remote island scheme.

Left: Charity. 1898. East Nave, Craigrownie Church near Cove on Loch Long. Right: Nativity. 1892. South transept gallery of St Columba Church, Largs. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In North Berwick Parish Church, Adam provided striking illustrations for some of the Works of Mercy ‘I was sick and ye visited me -- naked and ye clothed me’ (Matthew 25.36), showing the pallid invalid lying weakly upon her bed, the vivid tones of the naked flesh contrasting with areas of dark glass. And in Craigrownie Church near Cove on Loch Long, there are two of Adam’s loveliest windows — Charity and Music — clearly demonstrating the late Pre-Raphaelite influence sometimes present in his work, in the features and form of the curving, flowing, red robed Figure of Charity (Fig. 6) and t he colourful mos aic background to Music.

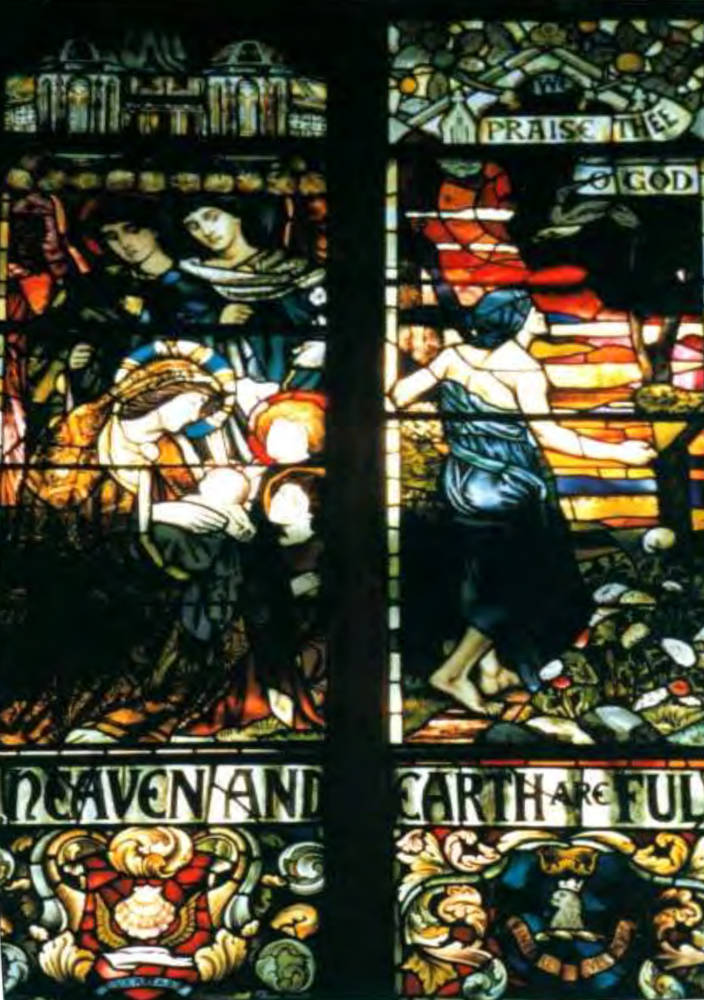

The apogee of Stephen Adam’s windows is found, in part, within two great Gothic churches, both built in 1892 at Largs on the Clyde Coast. In the south transept gallery of St Columba Church, is a splendid four-light Te Deum window whose theme is that of both Heaven and Earth glorifying God.17 The lower panels contain a very beautiful Nativity and a workman praising God at the dawn of a new day (Fig. 7). The Nativity is an unusual and strangely wistful scene, neither shepherds nor Magi are present. Instead, Adam proffers an intimate tableau of six Figures, the white infant Christ and Mary the Mother (in brown brocade, not Madonna blue) emphasised by the chiaroscuro background, the flashes of red, blue, gold, light green separately placed within this scene. The workman at the dawn of day has as its basis the text ‘Man goeth forth to his work and to his labour until evening’ (Psalm 104, 23.). The dawn is represented by long, horizontal bars of varied vivid colours combining with luxuriant blooms to create an oriental atmosphere, revealing again the influence of Japonisme upon Adam’s work. The areas of dark glass used by him in this late period are present in the outline of a tree. Dark glass is also used to dramatic effect in the transept gallery window in the adjacent Clark Memorial Church, where an angel with ruby wings appears to the centurion Cornelius.18

In this same church the Great West window is perhaps the most extravagant and overwhelming composition that Adam ever created -- a vast fantasia in glass whose central theme is that of Christ the Teacher, surrounded by young children and animals. Christ is placed in the centre of this huge five-light window, around him a scattering of texts related to children and childhood scenes and a kaleidoscope of colours forming a vast composite in which Alfred Webster’s involvement is almost certain (as it also was in the St Columba Te Deum window, this duly attested in the guide to this Church).

Fig. 8. Corona Vectrix. 1903. Kilwinning Abbey Church.

This eclectic selection of Adam’s ecclesiastical glass concludes with two of his dramatic compositions. His Corona Vectrix window in Kilwinning Abbey Church in North Ayrshire was installed in 1903 in memory of the Reverend William Lee Ker. Paul is shown preaching in a stirring fashion, his words of advice to Timothy (from II Timothy i.7) appearing on a tablet behind him23 (engraved with the stylish lettering of the period), and soldiers and citizens are grouped around him, the areas of dark glass adding to the dramatic effect of this composition (Fig. 8).

Fig. 9. Baptismal window. Episcopal church, Dumbarton.

In Rowand Anderson’s slender and elegant Gothic episcopal church in the county town of Dumbarton,19 is a Baptismal window installed beside the font at the entrance to the church, from this same period, but very different in composition. This is a futuristic window ahead of its time (like the Teacher’s Window in Largs Clark Memorial Church), in a strong, bold palette of reds and golds. This window is a significant departure from earlier nineteenth-century Figure drawing, foreshadowing the coming changes in stained glass in the new century now dawning. A magnificently drawn and monumental angel fills the opening, his beating wings forming the entire background (Fig. 9), a late-Pre-Raphaelite influence one again palpable. He holds in his arms a small infant: in complete trust, the two Figures are locked in each other’s gaze with a total absence of fear.

Secular Work

The Stephen Adam studio was also responsible for the production of much secular glass. From around 1870, accompanying the rise of the wealthy middle classes was a boom in suburban expansion around the great manufacturing cities. The inclusion of stained glass decoration was almost de rigueur within the new villas, terraces and mansions forming these affluent suburbs. Often, demand was met with a range of panels ordered from the illustrated catalogues of various stained glass studios and trade firms. Although mass- produced, this glass was often of a high standard, patterns being stencilled to save time with examples of animals and human Figures carefully painted by hand into the centre of the stencilled patterns. Heraldic and allegorical scenes were popular subjects making their appearance particularly in the mansions of the aristocracy and landed classes. The ‘Four Seasons’ also made a frequent appearance.19 Adam’s secular glass was thus widespread across Scotland. His Catalogue of 189520 illustrates examples in the Town Halls of Annan and Inverness, the Carnegie Libraries in Ayr and Dumfries, Glasgow’s Sick Children’s Hospital and New Mental Hospital, in the various mansions of industrialists and shipping magnates and in quality restaurants and commercial premises.

Left: Railwaymen. 1878. Formerly in Maryhill Burgh Hall. Right: Allegory of Art. 1877. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

This was an extensive and profitable branch of production. Some of the grand houses in Glasgow’s west end Devonshire Gardens contain glass by Stephen Adam. Here he maintains his Neoclassical style of figure drawing in a series of allegorical Figures representing the arts and sciences. Once again, backgrounds of dark glass are used to great effect to highlight foreground Figures. A striking example is his Allegory of Art window, where a pensive, golden-haired child is set almost photographically against a black background, itself contrastingwith rich blue glass and red flowers (Fig. 10).

Adam’s 1902 Catalogue notes the decorative scheme of glass executed for the huge refurbished mansion of the shipping magnate Sir Charles Cayzer, at Gartmore in Stirlingshire. The design of the elegant Art Nouveau panels above the principal entrance of Gartmore House are intricate and involved, incorporating the baronet’s coat of arms with its finely drawn three-masted galleon and the motto Caute Sed Impavide (Cautiously but Fearlessly). Clear glass of high quality has been leaded together with light grey tints and inset pebbles of blue glass to create a decorative art work, which a hundred years later still has a fresh, contemporary appearance.

For Broughton House, once the Kircudbright home of Adam’s friend, the Scottish artist E. A. Hornel, the studio contributed a cameo panel of the head of a Cavalier, splendidly drawn with long chestnut curls and impressive moustaches complementing a handsome face and alert eyes.

Context and legacy

Scottish painting was flourishing in the late 1890s. E. A. Hornel, with his Celtic mysticism and Japonisme, was but one artist among a talented array working in various genres at this time. William McTaggart and his series of emigrant ship paintings -- a ghostly ship sailing away from the western seaboard, spectral figures of old folk abandoned on the shore along with a keening collie dog -- are his own emotionally charged youthful memories of the Highland Clearances. Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s iconic Harvest Moon is a reminder that the famous architect was also a very fine painter. Images of unsentimental rural life from W. Y. Macgegor, James Guthrie, and E. A. Walton show the departure of the Glasgow Boys from the ‘Land of the Mountain and Flood’ imagery of earlier artists like Horatio McCulloch and his vast, pictorial Highland landscapes. The Glasgow Boys had a wider vision as the result of diverse studies in Glasgow, London, Antwerp, the Hague and Paris. The late-nineteenth-century Celtic Revival in Scottish decorative arts and painting gave birth to a series of unusual paintings by John Duncan, such as Tristan and Isolde and Angus Og, illustrating his belief that there was once a unifying Celtic culture to which all Scots were related.

New times, new themes, new styles, new artists — all this was part of Stephen Adam’s creative world — impacting in its own way upon Scottish stained glass, as the Edinburgh windows of John Duncan clearly show. Adam would have been well aware of these trends and influences as he practised and refined his art form, and some of them entered into his own work in stained glass.

Stephen Adam’s legacy to Scottish stained glass was a generous one in various ways. Of course, his prodigious output — in civic, domestic and ecclesiastical glass — is an ample legacy in itself, as the windows reviewed here may illustrate. However, his is not solely a contribution of beauty and decoration. There are deeper significances which make Adam a pioneering Figure in his chosen field.

In his preliminary study of Glasgow stained glass Michael Donnelly unfolds the three main periods of Adam’s work: the early period about which little seems to be known; the middle period of progression and colour experimentation, and the last and greatest period of his looser, freer style, incorporating elements of strangeness and fantasy (Donnelly, 13-15). Throughout this chronology there are distinct advances made by Adam which distinguish his stained glass.

There is, for example, a distinct iconography that leads away from the earnest, stilted tableaux of earlier windows, Adam interprets traditional themes in a more fluid and imaginative way- the richly coloured, bending Magi at Alloway and Pollokshields Churches, the pallid death-like invalid in Glasgow Royal Infirmary's ante-chapel,21 the beautiful miniature Agnus Dei trefoil in Craigrownie Church, the Angel and Infant in Dumbarton St Augustine's, his large triptych of Work, Zeal and Love at Pollokshields Congregational Church — are all examples of this difference. And in Scotland, Adam's iconographic schemes also entered new territory with their social and industrial themes. The Maryhill and Clydeport Authority panels are excellent examples of the latter and his large scale windows in Glasgow's Trinity Congregational Church (now the Henry Wood Hall) are examples of the former, with their galaxies of [9th-century social reformers and liberal thinkers, a singularly straightforward secular presentation compared to the usual standard pieties, and one that aroused criticism at that time (obituary).

We must also consider the different ranges of high quality, antique glass which Adam employed in tandem with a stronger, more advanced palette which brought to his work a distinct painterly quality, particularly when dark, almost black glass is used, to give dramatic effect. And in Adam's last phase, inset miniature work in the form of small cameos makes an appearance, incorporating different scales within a single window. The hand of Alfred Webster can be seen in this miniature work and, after Adam's death, would be developed more fully in his own studio windows to become an integral feature of Webster's style.23

Furthermore, it is the enigmatic element present in these later windows which sets them apart —that disturbing and slightly sinister quality mentioned above. The appearance of the blind cherubim, the watching child, the strange studies in physiognomy in various windows — all these aspects combine to form a new and different element in the changing iconography of the late nineteenth century. This is indeed the world of Late Romanticism — Walter Pater has described Romanticism as the addition of strangeness to beauty.·" With the late windows of Stephen Adam, this mysterious fusion was achieved in stained glass.

Nor is Adam's legacy confined to the windows he created and installed throughout Scotland: through his encouragement and example he enabled and nurtured another generation of fine stained glass artists in his studio, thus enriching Scottish stained glass well into the twentieth century. Two young artists of this period stand out prominently because of the talents and gifts they possessed and what they learned from Stephen Adam.

The first of these is the artist's own son, also Stephen Adam, who followed in his father's footsteps to join his studio fresh from Glasgow School of Art. Tragically, a bitter quarrel would later drive them forever apart and the son who had been made a partner in the business would emigrate to America, thus depriving Scotland of a fine talent. There are not many extant examples of Stephen Adam's Junior's windows, but what does survive shows him to be an artist of exceptional talent whose work contains some strong influences from his father's studio, although in a different colour palette and sometimes with even stronger dramatic emphasis. Donnelly describes Adam Jr's colours as lighter and cooler;" but there is also a balanced use of a darker spectrum showing Adam Sr's influence. This is evident in the windows executed for Trinity Congregational Church in Glasgow in 1907 (now installed in St James the Less Episcopal Church in Bishopbriggs) which includes a powerfully dramatic study of Christ in Gethsemane (Fig. 11). The horror on the face of Christ as he contemplates his approaching tortures is graphically shown in this nocturne. Also worth pointing out is the use of bold horiz ont als in t he background which emphasise the drama.

Two works by those taught by Adam the elder. Left (Fig 11): Christ in Gethsemane. 1907. Stephen Adam. Jr. Right (Fig. 12): . Alfred Webster. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The quarrel which drove apart Adam and his son may have been caused by the presence in the studio of the second young artist of great promise, Alfred Webster, of whom much more could be written than is possible here. Webster already possessed the attributes of a great stained glass artist when he joined the studio in 1905, also fresh from his studies at Glasgow School of Art. He learned much from Adam Sr and soon a formidable array of talents and skills developed, moving quickly towards a full, mature style. In particular from Adam he inherited a powerful style of Figure drawing which he then developed in an individualistic and personal way. Clarity of line is another hallmark of his style. He was a skilled portrait painter, usually drawn from life models, as his Figures demonstrate in their various contexts. His palette moved away from the dominant colours of Adam Sr to incorporate a different range such as rich purple, leaf green, orange, light russet, pale blue, turquoise and ruby. Webster also learned and developed superb new techniques such as acid etching and abrading, which enhanced and enriched the surface of the glass. He was among the first to use thick, undulating white Norman slab glass, which provided the ideal basis for his powerful windows. In addition, Webster possessed that gift so necessary, but often elusive to the creative arts -- that of a highly fertile imagination -- which added sensitive and sometimes unusual dimensions to his windows. Importantly, Webster effectively used allegory in his windows (the great south transept window of Glasgow’s Lansdowne Church provides the best example),24 and this was an innovative feature which Douglas Strachan would later bring to full flowering in his own great series of windows in the Shrine in Edinburgh Castle’s Scottish War Memorial designed by Robert Lorimer.25

Webster owed much to Stephen Adam whose training he had received and absorbed. This debt is movingly expressed in one of Webster’s finest windows — a hidden miniature in a narrow corridor in New Kilpatrick Church in Bearsden. Titled The First Fruits, the window is inscribed to the memory of a teacher and friend, Stephen Adam (Fig. 12). The model for the boy angel was Alfred Webster’s young son, Gordon, who in due course would inherit his father’s studio to become a leading Scottish stained glass artist in his own day, Adam’s legacy passing in this way from one generation to the next. Alfred Webster’s developing genius was abruptly cut short by the First World War when he was fatally wounded at Le Touquet on the French battlefields on 24 August 1915, whilst serving as a combatant officer with the Gordon Highlanders (Obituary).

Finally, Stephen Adam’s legacy was one of goodwill to colleagues and a firm belief in indigenous talent. He held no circumscribed view of his own work and was generous in his praise of other talented artists in his book Truth in Decorative Art: >‘The west gable of Paisley Abbey -- there you have a window by the late Daniel Cottier, the pioneer of a better condition of things in Scotland as regards stained glass. Cottier’s glass has all the depth and richness of colour so predominant in a feature of the Cinque Cento glass in Saint Gudeles, Brussels. The glass of William Morris and his Pre-Raphaelite colleagues also inspired his warm approval: ‘windows by Morris & Co, designed by Burne-Jones, worthy of study... characteristic... is the sweetly drawn and thought fully coloured foliat ed det ails. The Figures are inserted as in medieval glass, as points or panellings of richer colour and there is a composure and rest in those placid, gentle Figures... .’ And he describes glass by Rossetti, Burne-Jones and William Morris in the Old West Parish Church of Greenock as ‘gems in stained glass... . Finer examples of modern work there is not in the United Kingdom. Adam also goes on to decry the ‘aggressive Munich type window’,38 a reference relating to the controversial scheme of windows installed by the Koeniglich e Glasmalere instalt in Glasgow’s Cathedral Church of St Mungo in the 1860s, the echoes of which were still reverberating strongly decades later.

Stephen Adam was hopeful for the future of his art, speaking of a Renaissance springing up ‘like a healthy sea breeze, which will, if maintained and encouraged, resuscitate in modern form the splendour and glory of the earlier work by strenuously avoiding the causes of decay occurring in the 17th century’ (Truth in Decorative Art). In particular Adam applied this Renaissance concept to Glasgow’s stained glass, soon to reach its zenith in the work of a galaxy of highly gifted Scottish artists. Glasgow was the city of his home, his studio and the centre of his life’s work and he viewed it as both a paradigm and opportunity for investment in indigenous talent in stained glass:

Like religion, art has a noble mission, and let us hope a fruitful and bright future, and evidence is not wanting that in our very midst there has sprung up an almost phenomenal renaissance of the Arts & Crafts. There is already a renowned Glasgow School of painting, and most decidedly there is a distinct Glasgow School of decorative art rapidly forming that shall yet stand second to none; and a special mission of this promising school will be to revive and produce Scottish and distinctly National Art Work. Stop the flow going from us, reverse the stream by showing our wealthy classes and connoisseurs, who now spend their money elsewhere, that at their hand is every decorative requirement for embellishing their homes and churches. [Truth in Decorative Art]

This was not a narrow, aggressive form of nationalism, introverted and malevolent. On the contrary, Adam was generous in his praise of English stained glass artists and their designs. Instead it was a cry from the heart pleading for recognition of native talent -- and it has a curiously contemporary sound. It reflects a sad Scottish syndrome, a belief that only beyond The borders of Scotland are to be found the pearls of great price. This is not cultural xenophobia, but rather a melancholy reality. Adam saw it clearly in his own time, in the long aftermath of the Munich imbroglio.26

In this sense Stephen Adam was indeed a truly Scottish artist. Not because he adorned his windows with national symbols, or counted among his commissions prolific examples of Scottish historical genre, developed what could perceived as a distinctive Scottish style. These elements would be apparent in the next twentieth-century generation of Scottish stained glass artists: Douglas Strachan, William Wilson, Mary Wood and Sadie McLellan to mention a few major names (see articles elsewhere in this issue). Adam was intrinsically Scottish in a different sense — by birth, education, training, home and place of work — of which he was not ashamed. Thus, the windows he produced were deeply Scottish within this broader context. He died in August 1910 and his obituary in the Glasgow Herald expresses clearly the qualities of his life and work:

death last night of Mr Stephen Adam, at his residence, Bath Street, Glasgow. Mr Adam, who was 62 years of age, had been in failing health for some time. For many years he occupied a prominent position as a decorator and an artist in stained glass.

He enjoyed a high reputation in his profession, Quickly gaining recognition, he found many outlets for his talents. Examples of his work adorn many edifices, not only in this country, but abroad. One of his most important commissions was a series of windows for the Royal Prince Albert Hospital, New South Wales. His local commissions are too numerous to detail, but mention may be made of the remarkable windows he designed for Trinity Church in Glasgow. These mark an entire departure from the conventional. They perpetuate the memories of such humanitarians as Thomas Carlyle, F. D. Maurice, and George Macdonald. The windows have attracted much attention and called forth some criticism, but there the or be is no question about the skill of their execution... . Personally Mr Adam was a most lovable man. He was courteous in bearing and possessed a fine fund of humour. For James Ballantine, his instructor he retained always a warm affection. Many celebrated workers in stained glass were, in turn, trained by Mr Adam. One of the ablest of his pupils, Alfred Webster, for the past seven years has collaborated in his work, and by him the business will be carried on.

Stephen Adam was steeped in the knowledge of the art of stained glass. He based his work on the best masters and he practised the art in its purest form. He had a fine colour sense, and although he handled the same theme many times his versatility was such that he imparted distinction to each work.

Stephen Adam was always happy in his designs.

Postscript ny Martin harrison

Iain Galbraith’s most informative article succinctly describes Stephen Adam’s artistic training in Edinburgh and Glasgow; we learn that Adam even received a medal in recognition of his abilities. From this it would be reasonable to assume that Adam was a capable artist, and that, given the (judiciously selected) quotations from the texts in his catalogues of 1895 and 1902, he was responsible for designing his studio’s stained glass. Yet Mr Galbraith mentions three freelancers — Robert Burns, David Gauld and Alex Walker — who supplied cartoons to Adam in the 1890s. Their employment raises certain questions: had Adam become overloaded with commissions by this time? or did he operate as the studio head perhaps as a kind of ‘artistic director’? and might he, therefore, have engaged ‘outside’ designers earlier than this?

The ramifications of the devolved design systems operating in nineteenth-century glass-painting workshops are, at present, incompletely understood. The evidence emerging, however, points to a highly complex situation, one which renders the attribution of Figures designs, in particular, extremely problematical. By a fortuitous coincidence, Lindsay Watkins’s guide to the stained glass of St Michael and All Angels, Helensburgh, arrived in time to be reviewed in this issue (See p. 255). The East window of the church, and the vesica above, were made by Adam & Small in 1881 (the main window is signed). Yet based on the illustrations in Mrs Watkins’s book, the Figural scenes in both windows can be confidently assigned, on grounds of style, to Harry John Burrow (1846-1882). As a designer, Burrow is usually associated with James Powell & Sons, but he was also a sought-after freelancer, for his hand is also identifiable in windows made by Fouracre & Watson, of Plymouth and Daniel Bell, of London. Furthermore, Burrow’s authorship of the Helensburgh Christ in Majesty lends support to my theory that he occasionally supplied Figure cartoons to Burlison & Grylls: the treatment of the angels at Helensburgh invites comparison with several Figures in the East window of St James, Bushey, Middlesex.

Insofar as we have a critical framework for Scottish stained glass, it has been established mainly through the publications of Michael Donnelly. Valuable as these are, they tend to marginalise the English contribution to stained glass north of the border. While this aspect of stained glass studies requires extensive research, it may be conjectured that — as a matter of fact rather than nationalistic pride — the Glasgow pioneers, Daniel Cottier and Stephen Adam, placed considerable reliance on English Figure draughtsmen, respectively Frederick Vincent Hart and Harry John Burrow.

Created 29 May 2016