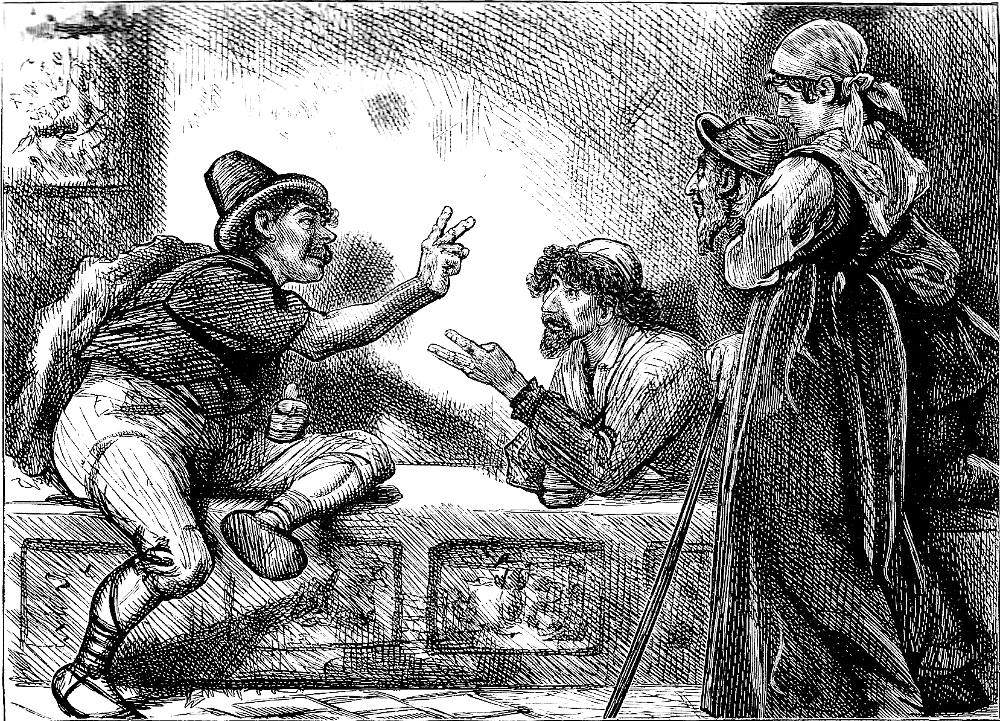

Playing at Mora by John Gordon Thomson, in Charles Dickens's Pictures from Italy, and American Notes, fifth chapter, "Genoa and its Neighbourhood," facing page 34. Wood-engraving by E. Dalziel, 4 by 5 7⁄16 inches (10 cm high by 13.3 cm wide), framed. Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.] Click on the image to enlarge it.

Passage associated with the Illustration

The men, in red caps, and with loose coats hanging on their shoulders (they never put them on), were playing bowls, and buying sweetmeats, immediately outside the church. When half-a-dozen of them finished a game, they came into the aisle, crossed themselves with the holy water, knelt on one knee for an instant, and walked off again to play another game at bowls. They are remarkably expert at this diversion, and will play in the stony lanes and streets, and on the most uneven and disastrous ground for such a purpose, with as much nicety as on a billiard-table. But the most favourite game is the national one of Mora, which they pursue with surprising ardour, and at which they will stake everything they possess. It is a destructive kind of gambling, requiring no accessories but the ten fingers, which are always — I intend no pun — at hand. Two men play together. One calls a number — say the extreme one, ten. He marks what portion of it he pleases by throwing out three, or four, or five fingers; and his adversary has, in the same instant, at hazard, and without seeing his hand, to throw out as many fingers, as will make the exact balance. Their eyes and hands become so used to this, and act with such astonishing rapidity, that an uninitiated bystander would find it very difficult, if not impossible, to follow the progress of the game. The initiated, however, of whom there is always an eager group looking on, devour it with the most intense avidity; and as they are always ready to champion one side or the other in case of a dispute, and are frequently divided in their partisanship, it is often a very noisy proceeding. It is never the quietest game in the world; for the numbers are always called in a loud sharp voice, and follow as close upon each other as they can be counted. On a holiday evening, standing at a window, or walking in a garden, or passing through the streets, or sauntering in any quiet place about the town, you will hear this game in progress in a score of wine-shops at once; and looking over any vineyard walk, or turning almost any corner, will come upon a knot of players in full cry. It is observable that most men have a propensity to throw out some particular number oftener than another; and the vigilance with which two sharp-eyed players will mutually endeavour to detect this weakness, and adapt their game to it, is very curious and entertaining. The effect is greatly heightened by the universal suddenness and vehemence of gesture; two men playing for half a farthing with an intensity as all-absorbing as if the stake were life. [Chapter 5, "Genoa and its Neighbourhood," pp. 30-31]

Commentary: An Interest in the Amusements of the People

From his work on the various London Sketches and his later editorial oversight for The Daily News, Household Words, and All the Year Round, Dickens had demonstrated a sincere interest in the amusements and recreations of the English urban working-class. As a handgame commonly practised in Italy, and especially in Genoa, Mora (or "Morra"), with its origins in ancient Greece and Rome, seems to have fascinated Dickens. It seems to have operated much as a coin-toss in the Anglo-Saxon world, since players used it to make personal and even business decisions, but it was also a pastime observed by passersby in the streets of Genoa, as Thomson's illustration suggests.

In Household Words five years later Dickens would defend modern popular culture in his manifesto essays, "The Amusements of the People" (1850), in Pictures from Italy he similarly immerses himself in the culture of the common Italian people. He tells us not — or not so much — about art and antiquity, but, for example, about men in red caps playing bowls and the national game of Mora in Genoa, the rules of which he describes . . . . [Ledger, pp. 88-89]

Related Material

- Samuel Palmer — Pictures from Italy

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. — The Brave Courier

- Thomas Nast — 'Located' near the Landing

- Thomas Nast — Near the Landing-Wharf

- Charles Dickens, the traveler — places he visited

- Genoa and its Neighbourhood

- Charles Dickens's Tours of Italy

- Dickens and Family at the Villa di Bella Vista (The Bagnerello), Albaro: July-September, 1844

- Charles Dickens, 1843 daguerrotype by Unbek in America; the earliest known photographic portrait of the author

Relevant Marcus Stone illustrations for Pictures from Italy

References

Dickens, Charles. Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Samuel Palmer. London: Chapman and Hall, 1846; rpt., 1850.

Dickens, Charles. American Notes for General Circulation and Pictures from Italy in Works. Illustrated by Marcus Stone. Illustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall: 1862, rpt. 1874.

Dickens, Charles. Chapter Five, "Genoa and its Neighbourhood." Pictures from Italy, Sketches by Boz, and American Notes. Illustrated by A. B. Frost and Thomas Nast. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1877. Pp. 10-13.

Dickens, Charles. Pictures from Italy and American Notes. Illustrated by A. B. Frost and Gordon Thomson. London: Chapman and Hall, 1880. Pp. 1-381.

Ledger, Sally. Chapter Seven, "'God Be Thanked: A Ruin!' The Embrace of Italian Modernity in Pictures From Italy and The Daily News." Dickens and Italy: Pictures From Italy and Little Dorrit, ed. Michael Hollington and Francesca Orestano. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars, 2009. Pp. 82-92.

Last modified 8 May 2019