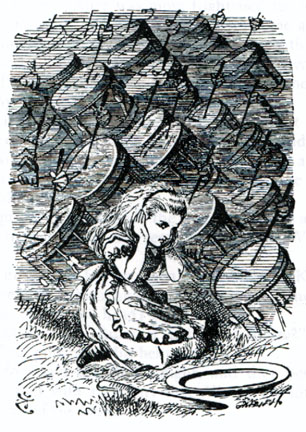

The drums began

Sir John Tenniel

Wood-engraving by Dalziel

Illustration for the seventh chapter of Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass (1871)

The drums began just as the Lion and the Unicorn were arguing about who got the lion's share of the plum cake. [What is the significance of the drums in ending the chapter?]

See below for commentary; mouse over the text for links.

In 2000 student assistants from the University Scholars Program, National University of Singapore, scanned this image and added text under the supervision of George P. Landow.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the site and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Commentary by Ray Dyer

John Tenniel's quite extraordinary contribution here brings us to a style of Victorian book illustration which would not be repeated for many decades. This rare achievement is perhaps matched in originality only by that of his Punch magazine colleague George du Maurier in certain of his more entertaining illustrations to Trilby of 1894.

Leighton Carter has usefully drawn attention to Tenniel's illustrative preferences for visual items, such as clothing, as opposed to speech. To this we may add sounds, such as the insistent drumming to which Alice is here subjected. One suspects that Tenniel felt impelled to find his own particular and innovative solution to Carroll's literary demand for him to depict a tense situation in which "the air seemed full of [the noise], and it rang through and through her head…."

Tenniel's creative originality has already prompted him to take on board elements from the contemporary Art and Crafts Movement (See Alice and the Looking Glass World armies), but here there is a new feature: an almost total and regular lattice-like structure of repeated drums - with just the busy hands of the drummer(s) as a further touch of genius. This encourages the viewer-reader to involuntarily synthesise the visual and almost incommunicable cacophony of sound.

Thankfully, Tenniel did not foreshadow the popular 1930s style of depicting literary noise in comics, with a few drums each with an attached balloon carrying words such as "Bang!" and "Boom!" in bold type. His ploy here looks further forward, to the 1960s and the likes of Andy Warhol, with his commercial advertising Pop Art depictions of "Fifty Green Glass Coca-Cola Bottles" (with the visual spread evoking the expansive experience of taste) and his iconic phalanx of even more numerously repeated images of Marilyn Monroe for the film industry — a visual tsunami of sex-appeal, in which the promise is only inferred and therefore acceptable.

Lewis Carroll was moved by powerful music scores, with their magnificent drum crescendos. They had captivated him all his adult life, probably even before he started writing his Journals in the 1850s. In the two decades prior to the appearance of Through The Looking Glass he had visited Exeter Hall in London for the resounding performance of the Messiah in what was termed a Soirée Musicale. The singer Jenny Lind (1820-1887), the Swedish Nightingale, also appeared in diary entries of March and December 1856 (2: 54, 122). In April 1868 Carroll and friends were again drawn to Exeter Hall and the great piece by Handel. The following month, he wrote to Tenniel to make a more determined effort to find time for the pictures of what was still being called Looking-glass House, (6: 18, 30). In his final finished children's tale also, Lewis Carroll would weave in numerous items of musicality, as with "Fairy Music" and a French Count interested in opera (Sylvie and Bruno Concluded, Ch. XII, entitled "Fairy Music").

Bibliography

Carroll, Lewis. Lewis Carroll's Diaries. The Private Journals of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. Vols. 2 and 6. Ed. Edward Wakeling. England: Lewis Carroll Society, 1994 and 2001.

_____. Sylvie and Bruno Concluded. London: Macmillan, 1893.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustration

John

Tenniel

Next

Last modified 20 July 2021