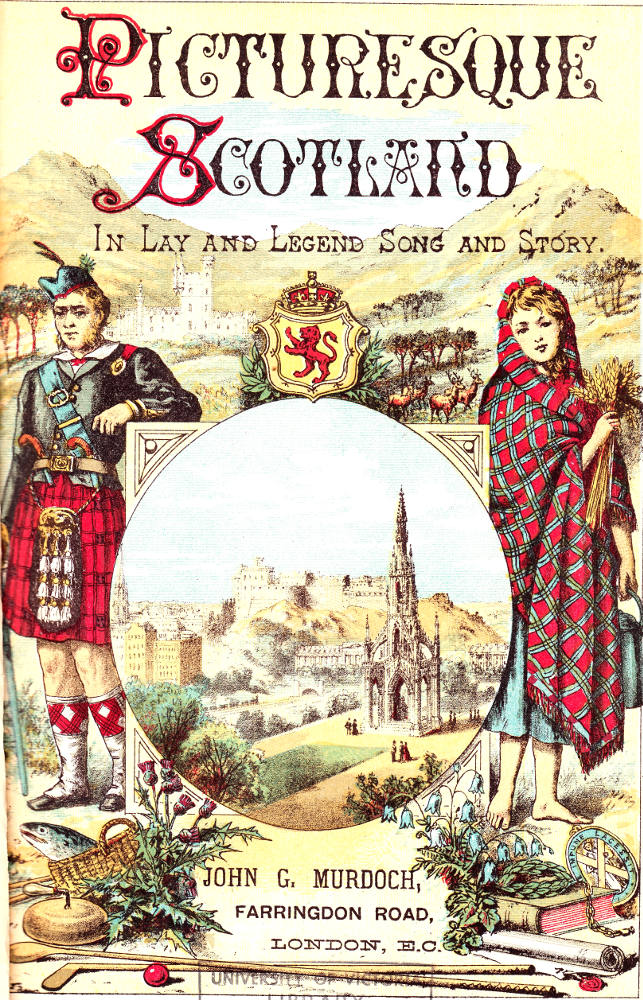

Walter Scott Monument (Title-page vignette, 1887?)

Picturesque Scotland: Its Romantic Scenes & Historical Associations Described in Lay and Legend, Song and Story

Sculptor: Sir John Steell (1804-91)

Architect: George Meikle Kemp (1795-6 March 1844)

21 cm x 14 cm (8 ⅜ by 5 ½ inches) framed; vignette, 9.1 cm high by 8.7 cm wide, framed.

Princes-street Gardens, Edinburgh

Related Material

Passage Illustrated: "Edinburgh — A Walk along Princes Street"

As we begin our walk, our attention is arrested by some of the pilgrims who have just arrived perhaps fresh from London, young men with faint suspicion of beard and moustache, with fingers gorgeously beringed, and faces marked by that strange combination of smartnesss and intellectual slightness with which one grows to be so familiar. You can see that they are patronising Edinburgh, and all of Edinburgh that pays them any attention is amused. They have got "Scotch caps" on, and have not yet had time to learn that even those elegant chimney-pots which they left in Hislington would not have looked so strange as these Balmorals. Their talk is equally impressive: — "Come, 'Arry, let's look at the guide-book! ah! — er — 'ere's a monument; ain't it a poor thing when you think o' the Griffin and the in Eastcheap? Whose is it? Ah, it's Sir Walter Scott, him as wrote them dry old novels that Miss Braddon has been making down into pennyworths for us." But enough of Harry and his brethren, for we have indeed come to the monument of Walter Scott. It stands in the East Princes-street Gardens, and is the most elegant structure of its kind in Scotland, or, some partial admirer might venture to say, within the United Kingdom. Its style is Gothic, and the arches in the lower and more massive portion are so striking in their resemblance to certain portions of Melrose Abbey, as to have suggested to many to conjecture that the architect was full of Melrose Abbey when he formed his plan. In the various niches are placed statuettes of the chief characters celebrated in the Waverley Novels; and under the canopy sits Sir Walter himself, with his favourite dog, Maida, at his feet. Thus, like a father among his children, the old man sits among his creations; historic figures and the figures of romance, as real to us as if they were historic, are here to do him filial reverence, and to remind us that he, who left no son to bear his name, and founded no dynasty, has left behind him in the world of letters a dynasty more potent, and a "house" more certain of survival, than many a prince or noble could boast. There is something to us, too, in the general structure of this high pile, ending in a pinnacle 200 feet high, which impresses us with its wonderful truth to its subject. [Pp. 12-13]

The architect was one George Kemp, a young man for whom, had he lived, a great future had no doubt been in store ; but this one work was to be his one memorial, and he died soon after its completion in 1844. The sculptor of the statue, an admirable work, was Sir John Steele.

By a winding stair the tourist can reach the top, from which a fine view of the city is obtained; but as we purpose to look upon Edinburgh from Calton Hill, we shall not be tempted from our walk to go the giddy round of steps. We have not all heads so good as that sailor of whom one so often hears in Edinburgh, who, accustomed to the masthead, not only went to the highest gallery of the monument, but mounted the pinnacle and stood upon that — if we mistake not — upon one foot. But there is something at the base of the monument which interests us almost as much for the moment as any possible view from the top. It is this inscription placed upon a plate in the foundation-stone, from the pen of Lord Jeffrey: —

"This graven plate, deposited in the base of a votive building — on the fifteenth day of August, in the year of Christ 1840, and never likely to see the light again till all the surrounding structures are crumbled to dust by the decay of time, or by human or elemental violence, may then testify to a distant posterity that his countrymen began on that day to raise an effigy and architectural monument TO THE MEMORY OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART., whose admirable writings were then allowed to have given more delight and suggested better feeling to a larger class of readers in every rank of society than those of any other author, with the exception of Shakspeare alone, and which were therefore thought likely to be remembered long after this act of gratitude on the part of the first generation of his admirers should be forgotten." On the one side of Scott's monument stands, at a little distance, the bronze statue of David Livingstone, an explorer scarce less great in other regions than those of romance; on the other, we note, proceeding westwards, another statue, also in bronze, to the memory of Mr. Adam Black — a man held in high esteem by his townsmen, and known throughout the world as the publisher of the Encyclopedia Britannica. Still moving westwards, we are next arrested by two Grecian-looking buildings, stretching from the left of us to the foot of the Mound, as the hill is called on which stands the Old Town of Edinburgh — the Royal Institution, and the National Gallery of Paintings, of which we shall have more to say by-and-by. Enough to say that these imposing buildings give, even to the passer-by, that suggestion of ancient Greece which reminds one of that vaunting title, "Modern Athens," which is sometimes attached to it. On either side of the Royal Institution stand two more statues, one in East Princes-street Gardens, the other in the more select West Princes-street Gardens, which skirt the base of the castle-rock. The former is that John Wilson, far better known as "Christopher North," the friend of Wordsworth and Coleridge, of De Quincey and of Scott; the other is that of Allan Ramsay, author of "The Gentle Shepherd," — like Wilson, a poet, but with more of a poet's fire, a man indeed of fine genius, the soft pastoral beauty of whose work lifted him into the foremost rank of Scottish song.

But we have almost forgotten — in these dreams of departed greatness — that we are on Princes-street at the fashionable hour, and that living men and women are about us. The mid-street is full of carriages, cabs, and hansoms; and the pavement is crowded with a more mingled mass of human beings. Now we meet, perhaps, several hearty-looking, well-fed, well-bred men walking arm-in-arm — a fashion more possible than in London — perchance an "advocate" who has done with his clients for the day, linked to some well-known local divine, who has spent the morning in his study, and comes out before dinner to meet his friends and talk of doings in kirk and state. Anon, it is a pair of straight-up, stiff-collared youths, not yet out of their teens, each with that appearance of hauteur which promises that the next generation of Edinburgh men is destined to be as proud as that which is passing away. Of couples there are many, — elderly merchants and their wives, young clerks and students with their sweethearts, perhaps a new married pair here and there, marked out by their studied determination not to be noticed, who have come to Edinburgh to spend a part of their honeymoon. Of laughing schoolgirls and hobbledehoy schoolboys there are not a few, just at the stage which a facetious friend describes as "noticing," who have got their lessons over, and, half by stealth, have found their way to Princes-street to play at being men and women. We dare not speak of the dresses. The ladies are seldom gorgeous in their attire; good taste — even severe taste — is the law in Edinburgh, and showiness is regarded as manifest vulgarity. [pp. 13-15]

Commentary

In studying the present-day state of the 1840-1882 monument, one can readily discern that it is much lighter in the nineteenth-century coloured engraving, reflecting the actual colour of the sandstone from the Binny Quarry. Several centuries of locomotive smoke from the nearby Waverley Railway Station have taken their toll on the monument. Although restorers have studied the problem and conducted numerous tests over the past two centuries, they have concluded that cleaning the surface would badly damage the soft stone.

Image scan and text Philip V. Allingham. [You may use the image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned it, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Colston, John. History of the Scott Monument, Edinburgh. Edinburgh, 1881. Rpt. Pitfield, Milton Keynes: Legare Street Press.

"Inauguration of the Scott Monument, Edinburgh." The Illustrated London News, No. 225, Vol. 9 (22 August 1846): 113-114.

"Scott Monument." Wikipedia. Viewed 20 September 2007.

Watt, Francis M., and Andrew Carter. "Title-page Vignette: The Scott Monument." Picturesque Scotland: Its Romantic Scenes & Historical Associations Described in Lay and Legend, Song and Story.. London: John M. Murdoch [1887?].

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illus-

tration

Scotland

Next

Created 15 June 2025