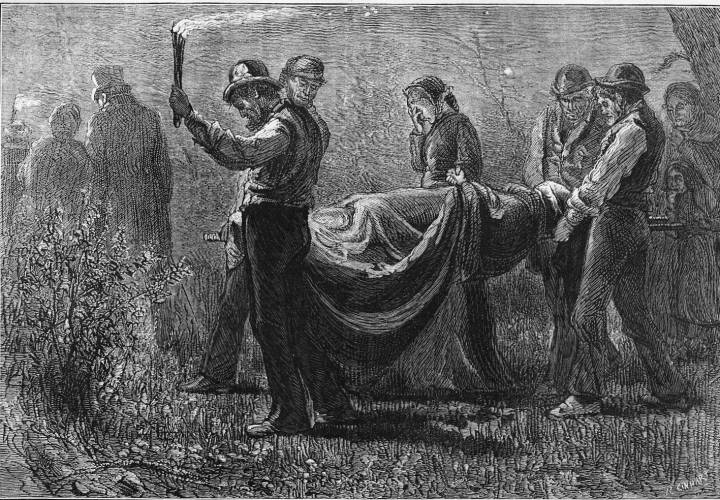

"And Through Humility, And Sorrow, And Forgiveness, He Had Gone To His Redeemer's Rest." by Charles S. Reinhart. 1844-1896. 11.8 cm high by 17.1 cm wide (full-page, vertically mounted). This wood engraving illustrates p. 220, the closing lines of Book Three, Chapter Six in Charles Dickens's Hard Times, which appeared in American Household Edition, 1876.

Commentary

Although previous illustrators have regarded the Stephen/Mrs. Blackpool/Rachael plot as subordinate to the main plot (Louisa/Tom/Mr. Gradgrind/Sissy Jupe), daringly Reinhart has chosen to focus the reader's attention on the fate of the conflicted factory-worker by making him the subject of the initial illustration, a full page staging of Stephen's being returned to Coketown from the mouth of the Old Hell Shaft.

Through the narrator's shifting into the high mimetic register of The New Testament the melodramatic language of the scene at the mouth of the Old Hell Shaft dissolves into sacred text as Stephen achieves a linguistically-engendered apotheosis. Reinhart has striven to convey the almost operatic emotion of the moment through a silent tableau on a shallow stage by reifying six of the figures in the procession. His style here is representative and suggestive rather than realistic: instead of a "throng," a mere metonymical nine figures people the shallow stage; instead of "fields" and ³lanes," Reinhart gives us a bush (left), stunted grass (foreground), and part of a tree-trunk (upper right). Although the letter-press speaks of "lanterns" and "torches" raised before the litter, the procession here is illuminated by a single, guttering torch held aloft by the despairing leader.

We cannot distinguish the surgeon and pitman from the working class litter-bearers--all are united and equal in grief and despair. Rachel still holds Stephen's as he has asked her to do before expiring on the litter, the shadowy figures of Louisa and her father (identifiable only by his top hat) fill the void above the bush (upper left), but neither of the female figures at the extreme right is consistent with the young womanly figure of Sissy Jupe that Reinhart gives us in plate 12. His face covered, as in the text, Stephen is a draped corpse rather than the gangly mechanic Reinhart gave us in plate 4, the blanket becoming a funeral shroud and giving him the massive dignity of a national hero such as Lord Nelson (interred with martial pomp in 1805 in London's St. Paul's Cathedral) or The Duke of Wellington (borne to his rest on the same gun-carriage as Nelson in 1852).

Anticipating Rodin's Burghers of Calais (1884), Reinhart's monumental procession moves stoically at a dead march, a pre-Marxist affirmation of proletarian solidarity in response to the carelessness of the exploitative, factory-owning and stock-investing class that has neglected to neutralize the danger of abandoned diggings. In vain in Reinhart's rendition of the tragic scene do we look for Stephen's guiding star which in the letter-press leads the party back to Coketown, and the sun has set, leaving a grey-washed twilight well suited to the text's "mournful silence."

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Houfe, Simon. The Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century British Book Illustrators and Caricaturists. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors' Club, 1978.

Pennell, Joseph. The Adventures of An Illustrator Mostly in Following His Authors in America and Europe. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1925.

Created 22 September 2002

Last modified 6 January 2020