Abstraction & Recognition

Phiz (Hablot K. Browne)

13.5 cm high by 10.3 cm wide

Dickens's Dombey and Son, Chapter 46; facing 236 in the second volume of the Illustrated Library Edition (1880)

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home—> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Phiz —> Dombey & Son —> Next]

Abstraction & Recognition

Phiz (Hablot K. Browne)

13.5 cm high by 10.3 cm wide

Dickens's Dombey and Son, Chapter 46; facing 236 in the second volume of the Illustrated Library Edition (1880)

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

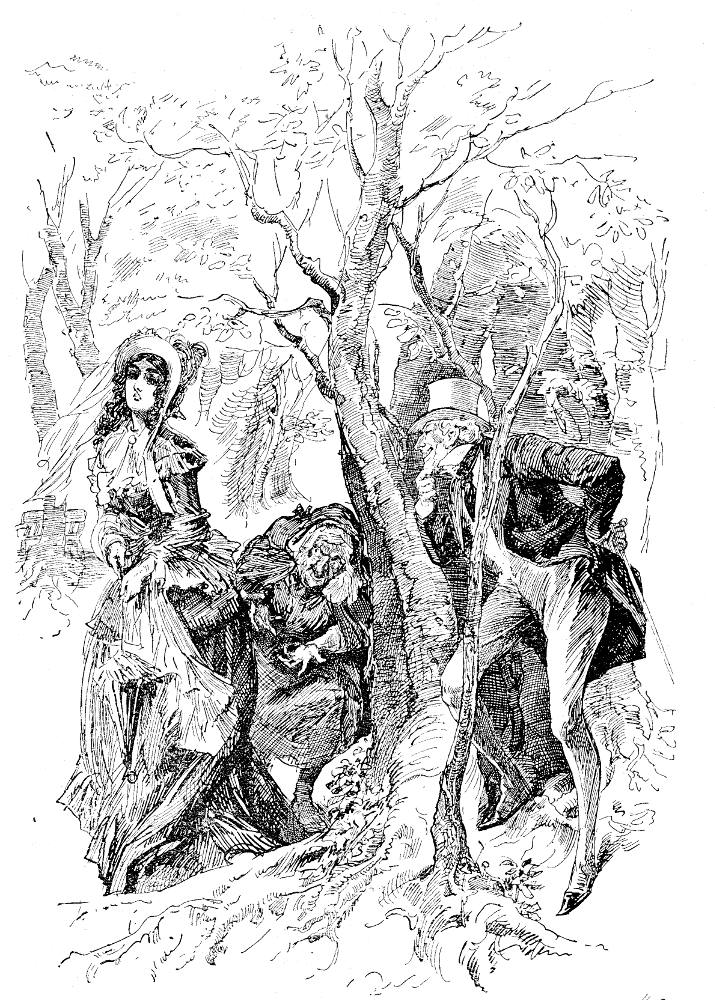

The only decided alteration in him was, that as he rode to and fro along the streets, he would fall into deep fits of musing, like that in which he had come away from Mr. Dombey’s house, on the morning of that gentleman’s disaster. At such times, he would keep clear of the obstacles in his way, mechanically; and would appear to see and hear nothing until arrival at his destination, or some sudden chance or effort roused him.

Walking his white-legged horse thus, to the counting-house of Dombey and Son one day, he was as unconscious of the observation of two pairs of women’s eyes, as of the fascinated orbs of Rob the Grinder, who, in waiting a street’s length from the appointed place, as a demonstration of punctuality, vainly touched and retouched his hat to attract attention, and trotted along on foot, by his master’s side, prepared to hold his stirrup when he should alight.

"See where he goes!" cried one of these two women, an old creature, who stretched out her shrivelled arm to point him out to her companion, a young woman, who stood close beside her, withdrawn like herself into a gateway.

"Mrs. Brown’s daughter looked out, at this bidding on the part of Mrs. Brown; and there were wrath and vengeance in her face.

"I never thought to look at him again," she said, in a low voice; "but it’s well I should, perhaps. I see. I see!"

"Not changed!" said the old woman, with a look of eager malice.

"He changed!" returned the other. ‘What for? What has he suffered? There is change enough for twenty in me. Isn’t that enough?"

"See where he goes!’ muttered the old woman, watching her daughter with her red eyes; "so easy and so trim a-horseback, while we are in the mud."

"And of it," said her daughter impatiently. "We are mud, underneath his horse’s feet. What should we be?"

In the intentness with which she looked after him again, she made a hasty gesture with her hand when the old woman began to reply, as if her view could be obstructed by mere sound. Her mother watching her, and not him, remained silent; until her kindling glance subsided, and she drew a long breath, as if in the relief of his being gone.

"Deary!" said the old woman then. "Alice! Handsome gall Ally!" She gently shook her sleeve to arouse her attention. "Will you let him go like that, when you can wring money from him? Why, it’s a wickedness, my daughter."

"Haven’t I told you, that I will not have money from him?" she returned. [Chapter 46, "Recognizant and Reflective," 236-237]

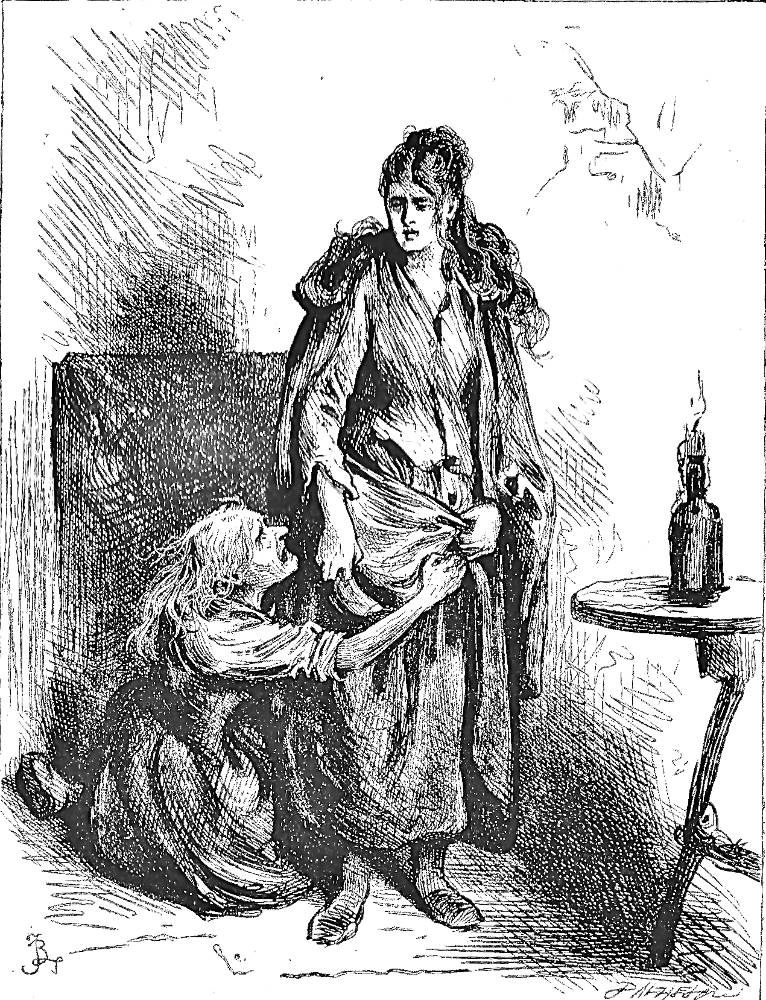

Left: Detail of the street-bills. Centre: Sir John Gilbert's title-page vignette for the American Household Edition of 1863, based on Alice's return in Ch. 34. Right: Furniss's study of the wizened crone and her beautiful daughter earlier, on the heath: Alice Brown and Her Mother

Steig notes how Phiz has used stopping out to create areas of darkness which reflect the darkening of the story's tone and mood after the Dombeys' marital breakup. "Browne's emblematic imagination seems to have been stirred by the theme of sexual conflict, for in the next pair of plates he displays not only his skill as an etcher, but his ability to make use of melodramatic conventions to good effect" (99-100). In this illustration for Chapter 46, Abstraction & Recognition Phiz positions the hidden observer, the angry and even malevolent wronged woman, Alice Marwood, in a darkened gateway, "but the highlights and the aura of light about her head make her the dominant figure" (Steig, 100). Good Mrs. Brown, still very much a sinister witch, peeps out as Carker as he passes by on horseback, unaware of their scrutiny. Alice's crone-like mother, half her daughter's height, "blends and recedes into the shadows. The most interesting compositional achievement is the way Browne balances the 'abstracted' Carker and Rob against the 'recognizing' Alice and her mother, leaving space between the former lovers in the center of the etching for a collection of significant posters on the wall" (Steig, 100). The "random and tattered" posters behind Carker and Rob the Grinder contribute to the reader's sense that this is no thoroughfare, but an uneven street leading through a squalid and poverty-stricken quarter of London. The long-out-of-date posters reinforce group the tattered condition of mother and daughter. However, the pastiche of embedded messages in the tattered posters bears some examination. As in the final illustration, Another Wedding, the fragmentary embedded messages of the street-bills, taken together, create a sense of a commenting chorus.

The tattered and fragmentary posters are apparently advertising theatricals and a masked ball. "Theatre City Madam" does suggest the prostitutes who were on the lookout for clients in the area of the Drury Lane Theatre. "To Those [about] to Marry" suggests both a marital comedy and a cautionary pamphlet. The embedded words may perhaps reflect Alice's fragmentary and even suppressed memories of her relationship with the "gentleman on horseback," James Carker, who seduced and abandoned her. Now returned from years of penal transportation, Alice is determined to inform herself about Carker's activities and movements as she begins to lay the groundwork for her revenge. Dickens has yet to reveal Alice's backstory and her connection to Edith Granger, the cousin whom she much resembles. Steig's commentary on these embedded texts and allusions is insightful:

The more obvious posters read "Observe" (Steel B only), alluding to the immediate subject of the plate; "Bal Masque," suggesting Alice's concealment; "Cruikshank/Bottle," in reference to the Hogarthian set of eight plates published in 1847, depicting the fall of a family, through drink, into poverty. The others are rather more complex. "Down Again / 6" (Steel B only) is, literally, a merchant's announcement of a drop in prices, but here it foreshadows the fall of Carker, who will be brought down thanks to Alice's vengeful scheming. "To Those About to Marry" would now undoubtedly carry the implied injunction, "Don't," but has a more somber overtone in this novel than in its earlier use in Martin Chuzzlewit. "Moses" would be the famous clothing merchant, who wrote poetical advertisements and took advertising space in the third part of Dombey and Son; but in the immediate context it probably has a broader meaning as well: with Edith about to run off with Carker, it evokes the Commandments against adultery and coveting one's neighbor's wife.

The remaining poster, "Theatre/City/Madam," is the most interesting allusion in the group. Massinger's The City Madam was produced in London as recently as 1844 (see Nicoll, 4: 442), and it contains enough similarities to Dombey to make inescapable the conclusion that it is the source for certain elements most relevant to the present illustration. [Steig, 100-101]

Left: Harry Furniss's earlier scene of Carker's secretly observing Alice

and her mother:

Dickens, Charles. Dombey and Son. With illustrations by H. K. Browne. The illustrated library Edition. 2 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, c. 1880. Vol. II.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne ("Phiz"). 8 coloured plates. London and Edinburgh: Caxton and Ballantyne, Hanson, 1910.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne ("Phiz"). The Clarendon Edition, ed. Alan Horsman. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr., and engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. III.

__________. Dombey and Son. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. 61 wood-engravings. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877. XV.

_________. Dealings with the Firm of Dombey and Son: Wholesale, Retail, and for Exportation. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. IX.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 16: Dombey and Son." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17, 294-337.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London (1899) edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Ch. 12, "Work, Work, Work." Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004, pp. 128-160.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 4. "Dombey and Son: Iconography of Social and Sexual Satire." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 86-112.

Vann, J. Don. Chapter 4."Dombey and Son, twenty parts in nineteen monthly installments, October 1846-April 1848." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. 67-68.

Created 8 August 2015 Last modified 8 February 2021