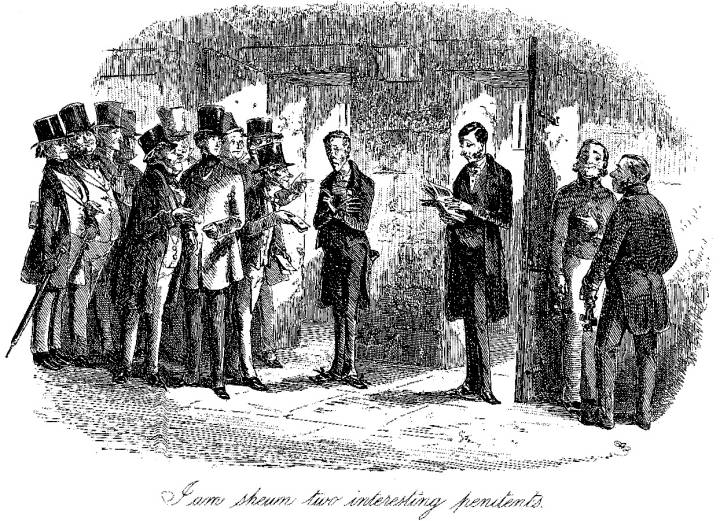

I am shewn two interesting penitents by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne). November 1850. Steel etching. Illustration for Chapter LXI, "I Am Shewn Two Interesting Penitents," in Charles Dickens's David Copperfield. Source: Centenary Edition (1911), volume two. 10.7 x 15.6 cm (4 ¼ by 6 ⅛ inches) framed, facing p. 504. Descriptive headline: "Number Twenty Eight" (505). [Click on the image to enlarge it; mouse over links.]

Passage Illustrated: The Hypocrites Littimer and Heep Duly Delude the Authorities

But, at last, we came to the door of his cell; and Mr. Creakle, looking through a little hole in it, reported to us, in a [502/503] state of the greatest admiration, that he was reading a Hymn Book.

There was such a rush of heads immediately, to see Number Twenty Seven reading his Hymn Book, that the little hole was blocked up, six or seven heads deep. To remedy this inconvenience, and give us an opportunity of conversing with Twenty seven in all his purity, Mr. Creakle directed the door of the cell to be unlocked, and Twenty Seven to be invited out into the passage. This was done; and whom, should Traddles and I then behold, to our amazement, in this converted Number Twenty Seven, but Uriah Heep! . . . .

[503/504] Twenty Seven stood in the midst of us, as if he felt himself the principal object of merit in a highly meritorious museum. That we, the neophytes, might have an excess of light shining upon us all at once, orders were given to let out Twenty Eight.

I had been so much astonished already, that I only felt a kind of resigned wonder when Mr. Littimer walked forth, reading a good book! [Vol. II, pp. 502-504].

Commentary: Can Such Offenders Ever Be "Reformed?"

In this concluding illustration, Phiz has responded to a much longer passage that editor J. A. Hammerton in The Dickens Picture-Book (1910) reduced to its essentials: "Traddles and I beheld in the converted Number Twenty-Seven, Uriah Heep! Twenty-eight was Mr. Littimer, who walked fourth reading a good book! [Hammerton, 366]

Phiz's first illustration for the nineteenth (double) monthly number, issued in November 1850, completes the narrative-pictorial sequence that one might entitle "Uriah Heep's Progress" from arch hypocrisy to rebellious humility to boldfaced fraud, punishment. social ostracism, and, ultimately, further duplicity. For this first November illustration, Phiz focuses on the figures of two supposedly reformed offenders called "Twenty Seven" and "Twenty Eight," the numbers assigned by the penal institution to the long-headed Uriah Heep and the suave James Littimer. According to J. A. Hammerton, the illustration of the undiluted roguery portrayed by these deceptive egoists may be associated with the above extended passage.

Thus, Phiz has collapsed two textual moments into one scene, and had Uriah pocket the hymnal to distinguish him from Littimer (right), reading a rather thin Bible (perhaps just that tome of suffering and forgiveness, the New Testament). Neither "penitent" is dressed in standard prison uniform, but, perhaps merely for the sake of visual continuity, wear the swallowtail coats and dark waistcoats associated with middle-class respectability. Last seen in Steerforth and Mr. Mell, the sadistic schoolmaster, Mr. Creakle, has unexpectedly reappeared, just as in other Dickens novels, characters from earlier in the narrative have a habit of turning up later in the story, often to effect a plot resolution. Creakle is the somewhat rotund, benign-looking member of the establishment standing immediately beside David Copperfield. The only other youthful face in the congregation, seen immediately over Copperfield's shoulder, must be that of Traddles. On the extreme right of the plate stand the two uniformed turnkeys (not actually mentioned in the text), whose knowing looks exchanged with each other suggest a more normative response to this theatre of contrition, with the lead actors making a palpable hit, if one may judge by the appreciative smiles and gestures of the prison commissioners, which Dickens has not delineated in any detail, and therefore more or less cut from the same cloth in this illustration of disinterested establishmentarian public benevolence. Our delight in the scene is that the persuasive pseudo-penitent rogues have so easily deceived the prison governors.

Mr. Creakle, former headmaster at Salem House, has graduated to another title and another post of responsibility: as a Middlesex Magistrate, he finds himself on the board of governors for a "solitary system" penitentiary which Dickens has presumably modelled on Pentonville Prison (a large penal institution located near Holloway, in the County of Middlesex), functioning on the modern and "highly scientific" principle of "solitary confinement" since its opening in August 1842. The two "interesting penitents" whom Creakle extols to Traddles and Copperfield earlier in the sixty-first chapter, "I Am Shown Two Interesting Penitents," as worthy of inspecting as exemplars of "the only true system of prison discipline" (499) turn out to be none other than Uriah Heep and Steerforth's gentleman's gentleman, Littimer. Guilty of crimes other than those with which David the narrator has already associated them, Prisoners No. 37 and 38 have been incarcerated for bank fraud and robbery respectively. Phiz has made the pose of the one to reflect that of the other, just as their statements of contrition and confessions of their "follies" seem to have been jointly developed. Both hypocrites, too, develop the notion that they are the ones who have been wronged, and that Copperfield, Traddles, and Mr. Wickfield should bear the responsibility for their misdeeds; but, of course, the pious frauds make much of uttering their professions of forgiveness, striking exactly the desired effect for the sober-sided, silk-hatted Board of Commissioners. Traddles and Copperfield, centre, are the only two among the distinguished guests who appear unimpressed by this cant and outward gestures of spiritual reform.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Personal History of David Copperfield, illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Centenary Edition. 2 vols. London & New York: Chapman & Hall, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1911.

Hammerton, J. A., ed. The Dickens Picture-Book: A Record of the Dickens Illustrations. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Created 7 March 2010 Last modified 26 August 2022