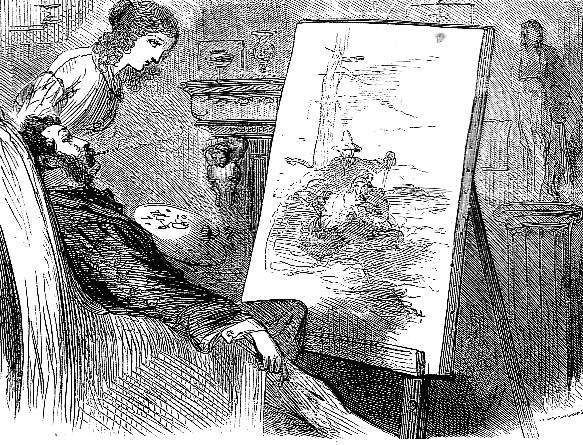

Mr. Sparkler under a Reverse of Circumstances by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) from Dickens's Little Dorrit, Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 6, "Something Right Somewhere" (November 1856: Part Twelve), facing p. 426. 10 cm high by 16.5 cm wide, vignetted.

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

In effect, the swain was standing up in his gondola, card-case in hand, affecting to put the question to a servant. This conjunction of circumstances led to his immediately afterwards presenting himself before the young ladies in a posture, which in ancient times would not have been considered one of favourable augury for his suit; since the gondoliers of the young ladies, having been put to some inconvenience by the chase, so neatly brought their own boat in the gentlest collision with the bark of Mr. Sparkler, as to tip that gentleman over like a larger species of ninepin, and cause him to exhibit the soles of his shoes to the object of his dearest wishes: while the nobler portions of his anatomy struggled at the bottom of his boat in the arms of one of his men.

However, as Miss Fanny called out with much concern, Was the gentleman hurt, Mr Sparkler rose more restored than might have been expected, and stammered for himself with blushes, "Not at all so." Miss Fanny had no recollection of having ever seen him before, and was passing on, with a distant inclination of her head, when he announced himself by name. Even then she was in a difficulty from being unable to call it to mind, until he explained that he had had the honour of seeing her at Martigny. Then she remembered him, and hoped his lady-mother was well.

"Thank you," stammered Mr. Sparkler, "she's uncommonly well — at least, poorly." — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 6, "Something Right Somewhere," p. 427.

Commentary

After the melodramatic violence of Gowan's attack upon his own dog to preserve his model, Blandois, Dickens interjects a farcical scene in which Edmund Sparkler, Mrs. Merdle's son, in trying to give Fanny Dorrit has calling card, loses his balance and falls into the bottom of his gondola — a classic example of "streaky bacon" construction which alternates serious and comic scenes. Continuity between the previous, dramatic illustration and this comic interlude is afforded by the figures of Amy (left) and Fanny (centre).

As in the companion illustration, Instinct stronger than Training in the same instalment, the scene is the romantic and rapidly decaying city of Venice. However, whereas Phiz here had illustrated the chapter set in Venice by portraying the studio of Henry Gowan above a bank on an islet, he now provides both physical comedy and local colour, putting young Sparkler in a characteristically awkward position while revealing Amy's genuine concern for his safety. Phiz has turned Fanny's face towards Edmund Sparkler, so that readers must supply Fanny's expression in witnessing the young man's discomfiture for themselves. Undoubtedly, Fanny is barely controlling a smile as she watches Sparkler's struggling to regain his composure, for this accident is certainly gratifying to a young woman who had been snubbed so recently by his mother.

Pertinent illustrations in other early editions, 1867 to 1910

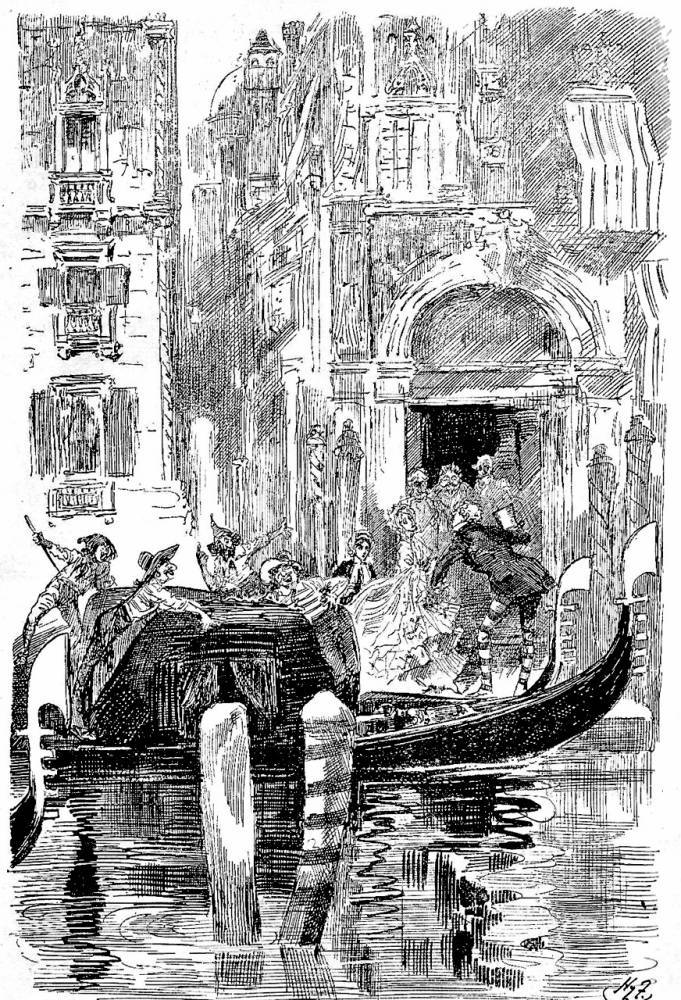

Left: Eytinge, Junior's dual study of the delicate, tentative bride and the boorish artist-husband, Mr. and Mrs. Henry Gowan (1867). Right: The Harry Furniss realisation of the gondola scene at the quay later that same day, as Fanny attempts to put the obtuse Edmund Sparker in his place, Miss Fanny meets an acquaintance (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

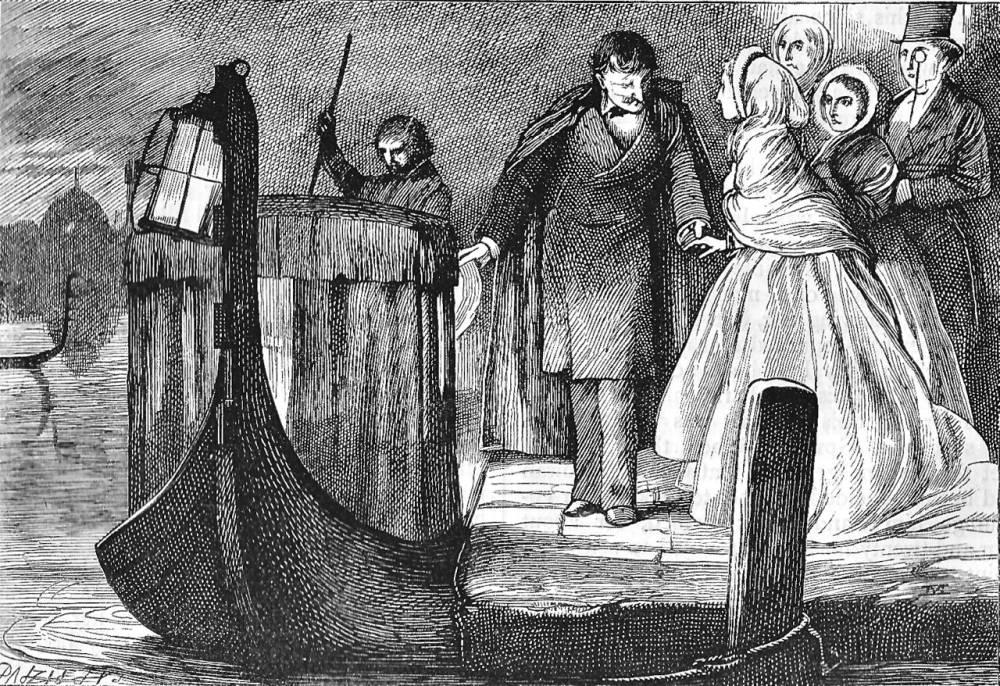

Above: Mahoney's British Household Edition scene at the quay which underscores Blandois' vindictive character, even as it provides local colour with a Venetian gondola and a domed church (possibly San Michele in Isola) in the background, On the brink of the quay, they all came together (1873). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Phiz. The Authentic Edition. London:Chapman and Hall, 1901. (rpt. of the 1868 edition).

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 12 May 2016