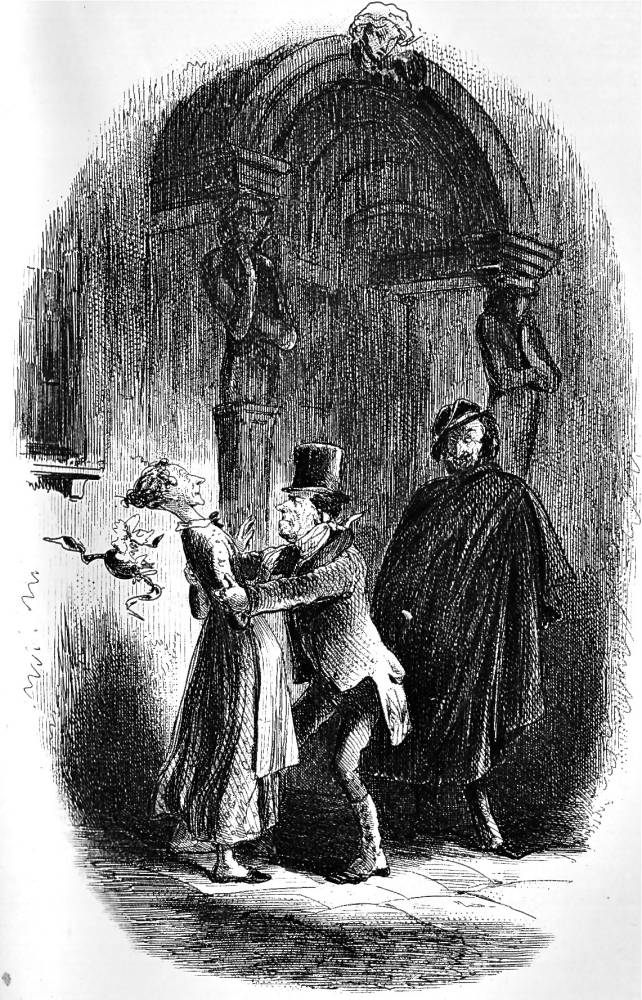

Mr. Flintwinch has a mild Attack of Irritability

Phiz (Hablot K. Browne)

August 1856

14.9 x 9.5 cm vignetted

Dickens's Little Dorrit, Vol. 12 of the Authentic Edition, Book the First, "Poverty"; Chapter 30, "The Word of a Gentleman" facing p. 300. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

The book was published in the customary twenty monthly parts, December 1855 through June 1857, by Bradbury and Evans with a blue wrapper and forty plates designed by Phiz.

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. ]

Passage Illustrated

When Mr. and Mrs. Flintwinch panted up to the door of the old house in the twilight, Jeremiah within a second of Affery, the stranger started back. "Death of my soul!" he exclaimed. "Why, how did you get here?"

Mr. Flintwinch, to whom these words were spoken, repaid the stranger's wonder in full. He gazed at him with blank astonishment; he looked over his own shoulder, as expecting to see some one he had not been aware of standing behind him; he gazed at the stranger again, speechlessly, at a loss to know what he meant; he looked to his wife for explanation; receiving none, he pounced upon her, and shook her with such heartiness that he shook her cap off her head, saying between his teeth, with grim raillery, as he did it, "Affery, my woman, you must have a dose, my woman! This is some of your tricks! You have been dreaming again, mistress. What's it about? Who is it? What does it mean! Speak out or be choked! It's the only choice I'll give you."

Supposing Mistress Affery to have any power of election at the moment, her choice was decidedly to be choked; for she answered not a syllable to this adjuration, but, with her bare head wagging violently backwards and forwards, resigned herself to her punishment. The stranger, however, picking up her cap with an air of gallantry, interposed. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 30, "The Word of a Gentleman," p. 299.

Commentary

The picture offers an interesting fusion of comic characters and a gloomy architectural setting that equates the Clennam mansion with the Marshalsea. The Punch-and-Judy husband knocks the slight hat off his wife's head while the faintly demonic Blandois, having arrived from France with a letter of credit on Clennam and Company, lurks in the shadows, waiting to be admitted.

Rigaud-Blandois is a somewhat different matter [from Merdle]. Dickens' character seems to derive from the folk-fairytale and its later artistic versions (such as Hoffmann's) and thus in the text he gives the impression of representing a more general, nontopical form of evil than does Merdle. Yet to this reader, at any rate, Rigaud is most successful as an artistic creation when he appears most clearly as a diminution of the devil-type, whose demonism is shown as merely a pose convenient to his philosophy of personal power and absolute self-interest. In most of Phiz's portrayals this complexity cannot emerge, and Rigaud is little more than a weakly drawn demon. But in two effective plates Phiz does complement and enhance Dickens' conception of the character. His first appearance in England as Blandois is illustrated in "Mr. Flintwinch has a mild attack of irritability" (Bk. 1, ch. 30). He has just emerged from the shadows, to give poor fearful Affery a terrible start; in this plate, Jeremiah is shaking his wife for her reaction while Blandois looks on. A preliminary drawing (Suzannet) indicates that this was almost certainly intended first as a dark plate: it is drawn in charcoal with the kind of heavy tone that Browne rarely if ever employed for anything else; and rather than the close-up of the final version, it is a distant view of the same scene, with the figures very small but in similar positions. Perhaps the emphasis (though the sketch is too small and rough for this to be certain) was to be on the old Clennam house, which burgeons larger and larger in the novel until it comes forth as a symbol of the decay of society — reminiscent of the collapse of buildings in Tom-All-Alone's. It is suggested that the next crash will likely "be a good one." (The Gimbel Collection contains what seems to be a preliminary sketch of the final version, unreversed, with the background only roughly indicated; the second Suzannet drawing is the working one, reversed as usual, and quite detailed.)

It is possible that Dickens originally intended the opening of Part IX to concentrate more upon the house, and gave Browne directions to this end, but upon having written the chapter found that the characters were more important, and correspondingly gave new directions. In the final version, the demonic aspect of Blandois is played up, both in his black cloak and in the gleam of his eyes and teeth, while the grotesque figures decorating the doorway look down upon the three characters with sinister anticipation. This illustration, even in its final form, could have been a dark plate, for it is literally dark enough; but the particular vein Dickens exploits seems better served by heavy manual shading than by the smoothness of a mechanical tint. The final version complements Dickens' text in the way it sets off against Blandois' gleaming eyes, upcurving moustache, and black cloak the rather horribly comic grotesqueness of Affery and Flintwinch — in other words, it is in a mixed vein which Phiz rarely brings off successfully in Little Dorrit. — Steig, Chapter 6, Bleak House and Little Dorrit: Iconography of Darkness,"p. 169-171.

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Victorian

Web

Little

Dorrit

Illus-

tration

Phiz

Next

Last modified 12 May 2016