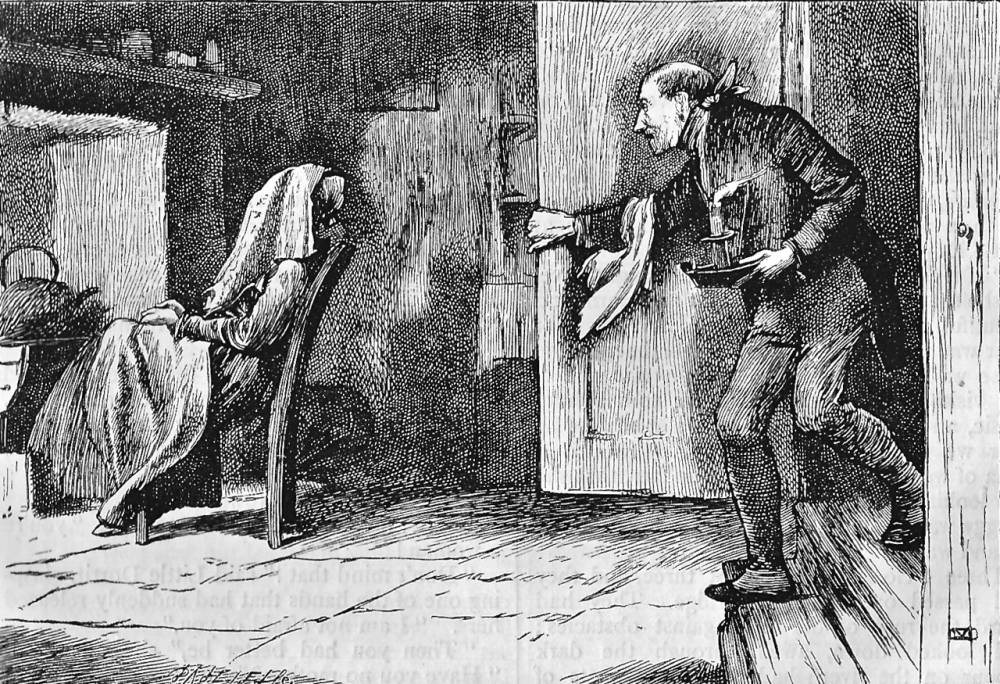

Mr. and Mrs. Flintwich by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) from Dickens's Little Dorrit, Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 15, "Mrs. Flintwinch has another Dream" (April 1856: Part Five), facing p. 158. 9.7 cm high by 12.5 cm wide, vignetted. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

Here the sound of the wheeled chair was heard upon the floor, and Affery's bell rang with a hasty jerk.

More afraid of her husband at the moment than of the mysterious sound in the kitchen, Affery crept away as lightly and as quickly as she could, descended the kitchen stairs almost as rapidly as she had ascended them, resumed her seat before the fire, tucked up her skirt again, and finally threw her apron over her head. Then the bell rang once more, and then once more, and then kept on ringing; in despite of which importunate summons, Affery still sat behind her apron, recovering her breath.

At last Mr Flintwinch came shuffling down the staircase into the hall, muttering and calling 'Affery woman!' all the way. Affery still remaining behind her apron, he came stumbling down the kitchen stairs, candle in hand, sidled up to her, twitched her apron off, and roused her.

"Oh Jeremiah!" cried Affery, waking. "What a start you gave me!"

"What have you been doing, woman?" inquired Jeremiah. "You've been rung for fifty times."

"Oh Jeremiah," said Mistress Affery, "I have been a-dreaming!" — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 15, "Mrs. Flintwinch has another Dream," p. 159.

Commentary

The picture offers an interesting juxtaposition of the agressive, Punch-like husband, Jeremiah Flintwinch, and the startled Affery, from whom he had just removed the apron with which she covers her face when terrified, or sleeping. Dickens excels at depicting such contrary dispositions linked by domestic service — Benjamin Britain and Clemency Newcome in The Battle of Life, the Christmas Book for 1846, being just such another couple, although Britain's wooden nature does not approach the flmboyant, hectoring posture of Mr. Flintwinch, Mrs. Clennam's clerk, business partner, and confidant. Phiz has captured his essence here: "A short, bald old man, in a high-shouldered black coat and waistcoat, drab breeches, and long drab gaiters . . . . There was nothing about him in the way of decoration" (Book 1, Ch. 3, p. 28). Phiz's Flintwinch may be "bent and dried" (28), but his glance is decidedly keen and his manner "knowing," to the point of superciliousness, a dour variation on the tricky servant of classical comedy.

Jeremiah Flintwinch, Affery's irascible husband, harbours a secret from his wife, but in her sleep she apprehends his confidential conversations with their employer, the dour Mrs. Clennam, although the contents of these dialogues so confuse her that she is sure that she must have dreamed them, as well as the strange noises emanating from the walls of the house, quite unlike the "rats, cats, water, [and] drains" that her husband proposes as the cause. Affery is utterly bewildered how, in her fugue state, Jeremiah can be so assertive with Mrs. Clennam, and what secret the pair are keeping from her that concerns Little Dorrit.

Pertinent illustrations in other early editions, 1867 to 1873

Left: Eytinge, Junior's dual study of the perpetually anxious Affery and her rough-and-ready husband, Mrs. Clennam's confidential servant, Mr. and Mrs. Flintwinch (1867), as described in Book 1, Chapter 3. Right: The American Household Edition frontispiece depicting Mrs. Clennam, Affery, Flintwinch, and Blandois, Closing In — Book II, Ch. XXX (1863). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: Mahoney's British Household Edition version of the same "downstairs" scene in the kitchen, He came stumbling down the kitchen stairs, candle in hand (1873). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Phiz. The Authentic Edition. London:Chapman and Hall, 1901. (rpt. of the 1868 edition).

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 21 May 2016