The following passages are extracts from George Titley's study of the illustrator (see bibliography), lodged in the University of Plymouth's Open Access Research Depository, PEARL, and kindly made avaiable on the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. The extracts have been selected, reformatted in house style, linked and illustrated by Philip Allingham, who has added his own notes at the end.

Thomas [Onwhyn], born in Clerkenwell, was the son of Joseph and Fanny Onwhyn. Joseph was an author, printer/publisher, bookseller and newsagent based in Catherine (aka Catharine) Street, The Strand, London. Fanny was also an accomplished artist and illustrator, best known for her portraits of actors of the day in their key roles. Some of her works are held in the Victoria and Albert Museum collections and other key art collections, both in the UK and abroad. Given this background, it is therefore not surprising that Thomas also became an artist, illustrator, and engraver, predominantly active between 1836 and 1861. [1-2]

Against this era’s background of "publish, publish, publish," and with the family "in the business," it is hardly surprising that Thomas, having proved his artistic capabilities during 1836, decided to break into the popular market. In 1837, under the nom-de-plume "Samuel Weller" (a character in the Pickwick stories), he designed and engraved 32 pictorial illustrations to Charles Dickens’s Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. These illustrations were not commissioned by either the publisher or the author so are sometimes described as "illegal" or "illegitimate" or "extra illustrations"! Pickwick was issued as a part work in eight parts, each part accompanied by a single commissioned engraving as a frontispiece to keep the cost down. The idea that "pictures" encouraged reading was now well established and many competent artists (we would probably call them entrepreneurs today) saw opportunities to produce and sell more illustrations to popular stories to meet a ferocious consumer appetite. Dickens’s stories and characters were so well described in the text that they made easy targets! In this Thomas was no different from many of his contemporaries, choosing a Dickens popular work and delivering what proved to be very popular illustrations – even if Dickens himself expressed his dislike! History shows that the phenomenon of inserting "extra" illustrations into a book to bring the story to "life," really began thanks to the popularity of Dickens works. It is estimated that there could be over 2,500 illustrations to Dickens works produced between 1830s and 1850s! In ... "Extra Illustrations and Grangerising: a Dickensian Phenomenon," Philip Allingham calls the practice "Grangerising" – the publishing of books with some illustrations but also with blank leaves where readers could insert their own or other suitable illustrations. Readers would collect the parts and any illustrations they liked from those available and have them bound into a single volume. This practice has led to there being multiple variant versions of a work, making it difficult to identify the official from the self-bind! Eventually, official "complete" editions with the plates included were also published. (Today copies of Dickens’ part work "books" with Onwhyn’s plates incorporated are now sought after and can be worth several thousand pounds!). Thomas went on to complete a second set of engravings for the work in 1848, but these were not discovered until after he died and were first published posthumously in 1894. [10]

Although a talented engraver in steel or wood, and despite the very positive comments and reactions to his book illustration activity throughout the late 1830s and 1840s in journals such as The Age, Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, The Penny Satirist, The Satirist, or, The Censor of the Times, and The English Gentleman, at the end of the 1840s Thomas moved away from mainly illustrating others people’s stories. Instead, he started creating works that were "humorous" in nature, taking a fun look at fads of the day, e. g., water cures [hydrotherapy], the Great Exhibition of 1851, and crinoline[s] etc., or recording his view of everyday life, e. g. the sea-side, mining, yachting etc. This change of direction may well have been a consequence of the patronage of William Rock, proprietor of Rock & Co., Printers, as many of these topical engravings in vignette form appeared initially as illustrated letter papers of which his firm was the major producer. [10]

Final Years

An oft quoted contemporary commentary states that, on his father’s death, Thomas seems to have "retired" from illustration and possibly became a retailer, continuing the family retail business for around 20 years until his own death in 1886.... Thomas’s illustrative work seems to mainly stop early in the 1860s. (The last work identified by this research is an engraving of "Lady Godiva and Peeping Tom of Coventry" in 1869). By the early 1860s, his father would have been in his 70s, so it would appear likely that the need to support him and the family business did take precedence.... Thomas died of old age on the 21 January 1886 at 9 May’s Building, London..... The index entry on the UK Wills and Probate "Post 1858" website ... provides the following entries, and show[s] that Thomas died with a personal estate valued at £235. Administration (with a will) was granted to his wife, Maria on 9 March 1886. Maria died on the 10 March 1886, and her will was "proved," the sole executor being a William Dowding of 46 Carnaby Street, London. (There was a W.D. Dowding, a London solicitor). [13-15]

Pseudonym Confusion!

[C]onfusion is introduced by there being multiple users of the same, or similar, synonyms to those confirmed as being used by Thomas. "Sam Weller" was used by at least two other persons, while there could be three variants of "Peter Palette," including "Peter Paul Palette." This was not an uncommon occurrence for the period, but it does complicate research over a century later! Not only did Thomas choose to use this key Dickensian Pickwickian character’s name as a pseudonym, so did other artists and writers. Those critics that review and reflect on Dickens' illustrators constantly refer to several artists using the name, but none provides details about anyone but Thomas! [16]

Additional notes by Philip V. Allingham

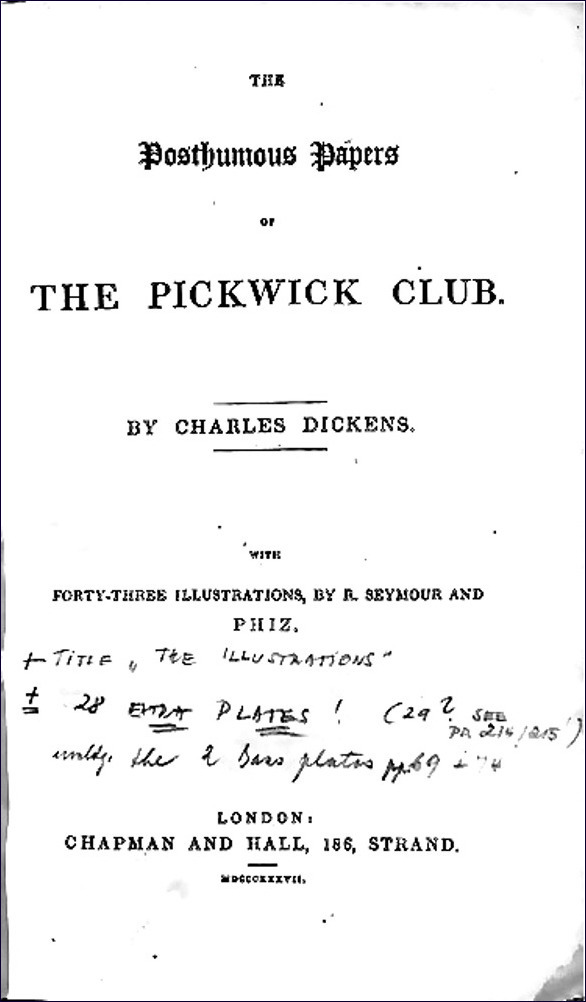

Shown on the left is Chapman and Hall's original 1837 title-page for the single-volume Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (November 1837), significant because of the annotation made long ago on it: "+ Title, 'The Illustrations' + 28 Extra Plates! (29? See PA 214/215) with the 2 bars [?] plates pp. 69 + 74." This indicates that an early owner of the volume edition had the "extra" Onwhyn plates inserted in the appropriate places of the volume.

In the thirty-two plates that he produced for Pickwick from March through November 1838, Onwhyn used his own initials on just fourteen (numbers 1, 11, 18, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, and 32), and the pseudonym "Sam Weller del" (Latin for delineavit, or "he drew it") only seven times (2, 4, 6, 7, 10, 15, and 19); eleven of the illustrations bear no name or initials whatsoever.

Note that Thomas Onwhyn also grangerized The Pilgrims of the Thames in Search of the National! by Pearce Egan (1836) and Nicholas Nickleby (1838-39). In this rare book, one finds a frontispiece and thirty-nine regular illustrations which Onwhyn and his publisher, Grattan and Gilbert, issued in nine monthly parts, although ten such parts were originally announced for 1838-39. As was the case with his Pickwick "extras," Onwhyn indicates on each against which Chapman and Hall page the plate should be positioned.

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Robert Seymour, Robert Buss, and Phiz. London: Chapman and Hall, November 1837. With 32 additional illustrations by Thomas Onwhyn (London: E. Grattan, April-November 1837).

Dickens, Charles. The Letters of Charles Dickens. 12 vols. The Pilgrim Edition. Ed. Madeline House and Graham Storey. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1880. Vol. 1 (1820-39).

Onwhyn, Thomas. Mr. & Mrs. John Brown's visit to London to see the Grand Exposition of All Nations: how they were astonished at its wonders!!, inconvenienced by the crowds, & frightened out of their wits, by the foreigners. London: Grattan, 1851.

Titley, Graham D. C. "Thomas Onwhyn: a Life in Illustration (1811-1886)." Pearl. University of Plymouth (2018-07-12).

Weller, Samuel. [Pseudonym of Thomas Onwhyn]. Illustrations to "The Pickwick Club," edited by "Boz." London: E. Grattan, 1837.

Created 6 March 2024y