illiam Newman (1817-1871) was born in Islington, then still a fairly rural area on the north-eastern outskirts of London. His father was a seed-merchant and his mother came from a farming background in the north of England: theirs was a "poor but respectable" family (Brown and West 144). Newman began his career as an illustrator in 1837 with the penny weekly, Figaro in London, staying with it until September 1838, and moving on to the more up-market Odd Fellow, for which he drew the weekly front cuts. He was then brought into Punch by its founders Henry Mayhew and Ebenezer Landells, under the editorship of Mark Lemon.

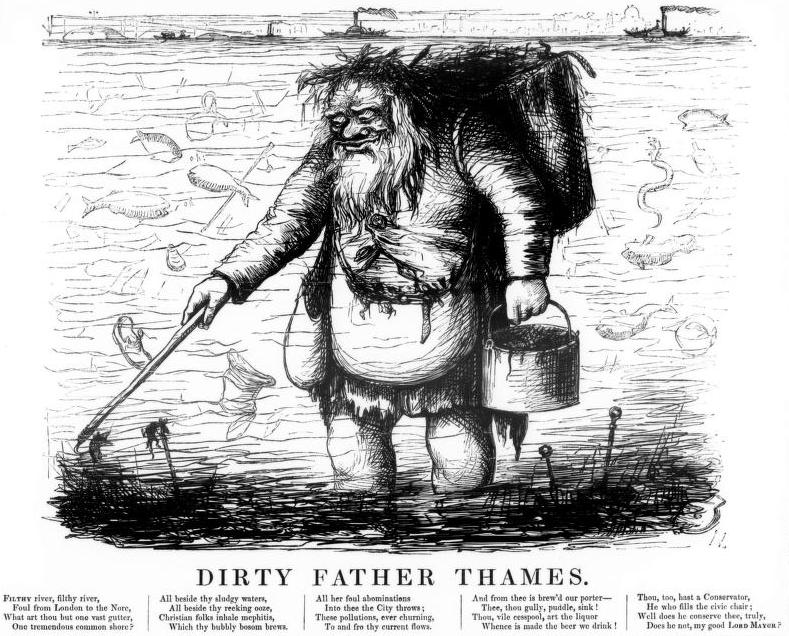

Dirty Father Thames, Punch (7 October 1848: 151). Click on the image to enlarge it, and for more information.

To Newman belongs the distinction of having drawn the very first title-page of the magazine, in which it set out its programme of "pleasant instruction" (1). For some time, says Marion Spielmann, he was one of Punch's top half-dozen contributors. Spielmann writes, for instance: "The 'Physiology of London Evening Parties,' . . . originally written by [Albert Smith] in 1839 for the Literary World, was illustrated by Newman, who was still a far more important man on Punch than [John] Leech" (305). According to Jane E. Brown and Richard Samuel West, whose research is indispensable to any study of Newman, he was also responsible for two of the magazine's most famous cartoons: "Twice his cartoons contributed to Punch’s commentary on the 1848-49 cholera epidemic: Dirty Father Thames in 1848, and Water Water Everywhere in the fall of 1849, the latter done by him when Leech had a serious bathing accident while holidaying with Dickens on the Isle of Wight" (151). Newman's last Punch cartoon appeared in April 1850, his departure probably owing much to social and religious factors — not only did he come from a lower class than other contributors, but he was a Catholic: another Catholic who would leave because of the periodical's anti-Catholic bias was Richard Doyle (see Brown and West 154).

For Newman, a period of financial uncertainty ensued. He had married in 1843, and now had a large brood of his own. He tried to keep his family afloat by selling books and writing children's "toy books," then becoming a freelance contributor for the feisty Diogenes and Comic Times. But his circumstances changed considerably when Henry Markinfield Addey, "a fashionable bookseller and publisher" of Old Bond Street (Brown and West 158), proposed to found an American version of Punch. This was to be entitled Momus, after the spirit of mockery and satire in Greek mythology. The Newmans emigrated to New York in 1860. It was a risky venture, and the new comic magazine soon failed. But Newman gained another commission, to illustrate Charles Lever's A Day's Ride in Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. More important in the long term, he was now ideally placed to commentate, like the prolific American cartoonist Thomas Nast, on the conduct of the American Civil War. In fact, he became one of the handful of artists key to the development of the mid-nineteenth-century transatlantic political cartoon.

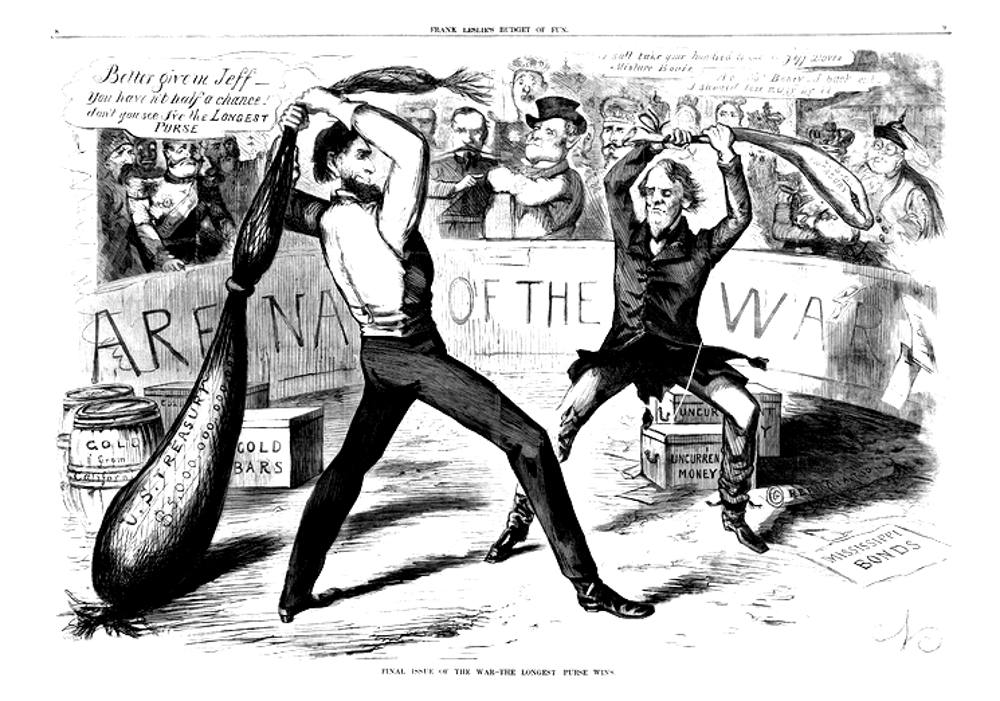

"Bold but not blindly ideological, the expatriate found in Frank Leslie's Budget of Fun a broader field for his energetic figures and wry Civil War commentary" (Garvey 418). Shown above is the March 1864 editorial cartoon, The Final Issue of the War — The Longest Purse Wins, published in Leslie's illustrated newspaper. Here, the Union and Confederate Presidents Lincoln and Jefferson Davis "comically slug it out with hefty money-bags in the 'Arena of the War,'" as Garvey puts it (418). After Newman's struggles in London, he was now able to make a new name for himself in the periodical press of America, and to achieve stability for himself and his family.

Newman was well established when, sadly, he died suddenly in New York at the age of fifty-two, from heart failure (see Brown and West 177).

Bibliography

Brown, Jane E., and Richard Samuel West. "William Newman (1817—1870): A Victorian Cartoonist in London and New York." American Periodicals, 17, 2: "Periodical Comics and Cartoons." (Ohio State University Press, 2007), 143-183. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20770984.

Garvey, Dana M. "William Newman: A Victorian Cartoonist in London and New York." (Review) Victorian Periodicals Review, 42(4): 417-18. DOI:10.1353/vpr.0.0097

"The Moral of Punch." Punch, Vol. 1 (1841). Internet Archive. Sponsored by the Kahle/Austin Foundation. Web. 16 May 2022.

Spielmann, M. H. Chapter VII, "Cartoons — Cartoonists and Their Work." The History of "Punch". London: Cassell, 1895. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/23881/23881-h/23881-h.htm#Page_168

Stevenson, Lionel. Dr. Quicksilver: The Life of Charles Lever. New York: Russell & Russell, 1939, rpt. 1969.

Sutherland, John. "Charles Lever." The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford U. P., 1989. 372-74.

Created 15 May 2022