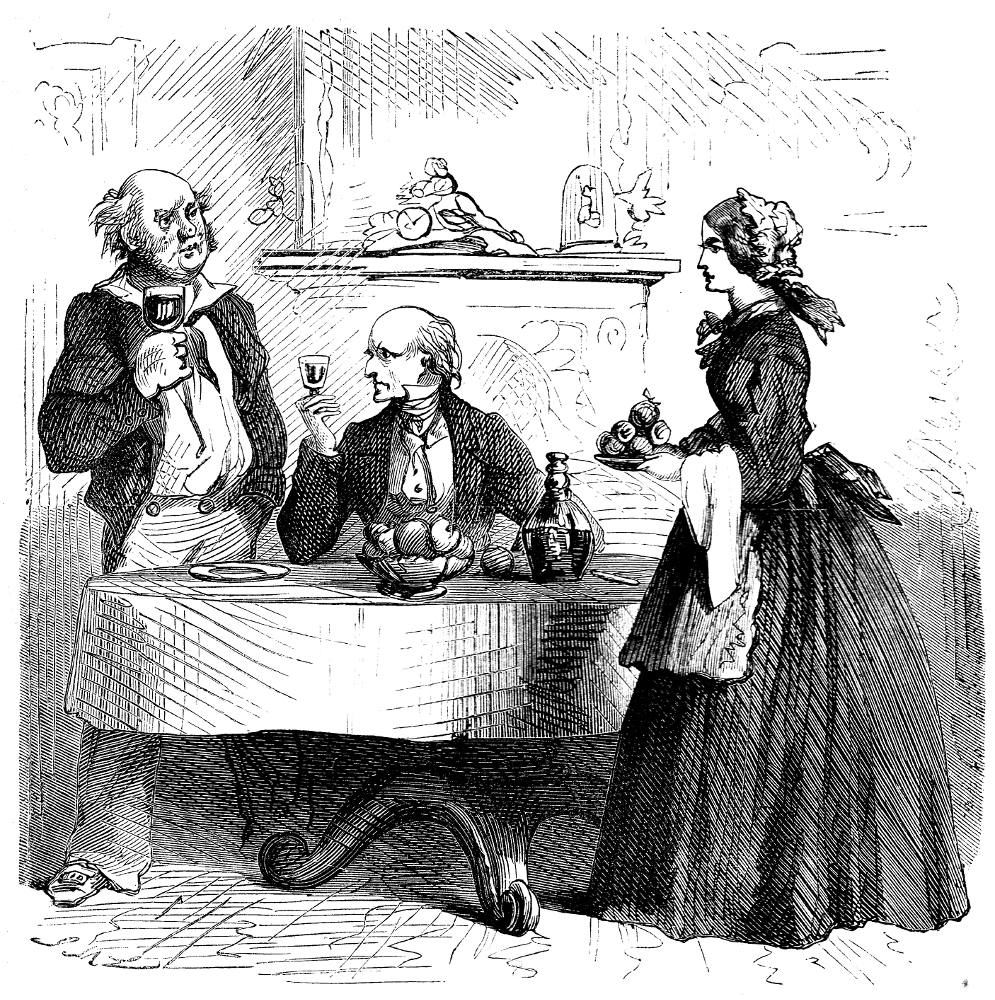

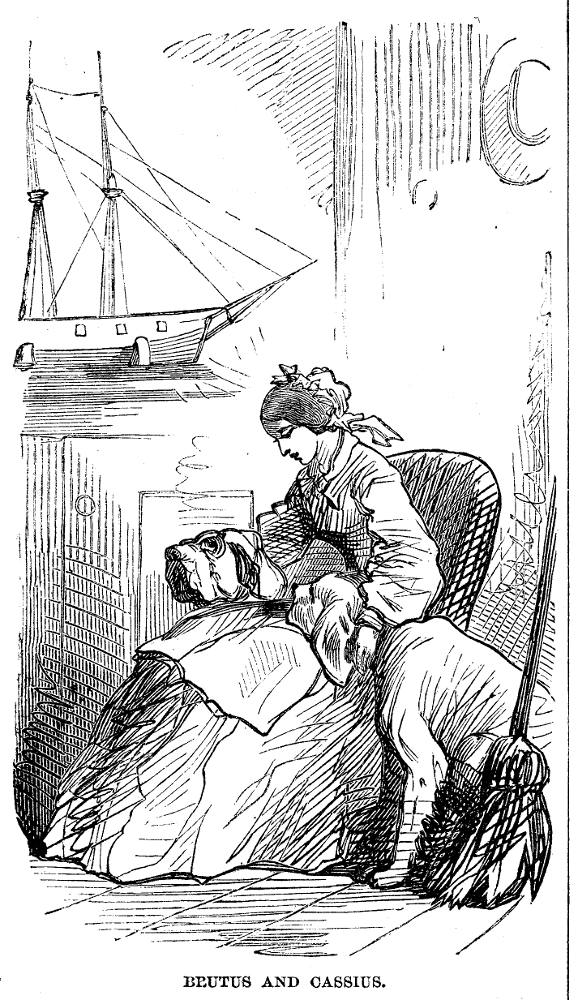

“West and by noathe, your honor.” Wood-engraving 11.3 cm high by 11.5 cm wide, or 4 ½ inches square, framed, for instalment thirty-nine in the American serialisation of Wilkie Collins’ No Name in Harper’s Weekly [Vol. VI. — No. 310] Number 39, “Between the Scenes. I. St. Crux-in-the-Marsh.” Chapter I, plus a captioned vignettte of Magdalen with her dogs, Brutus and Cassius (Chapter I: p. 797; p. 240 in volume): 9.6 cm high by 5.6 cm wide, or 4 inches high by 2 ¼ inches wide, vignetted. [Instalment No. 39 ends in the American serialisation on page 799, at the end of Chapter IV. This instalment with just “The Seventh Scene. I and II” ran in All the Year Round on 6 December 1862 as number 39. The British serial did not wrap up until 17 January 1863 with “The Last Scene,” Chapters 3 and 4.

Main Illustration: Magdalen, Admiral Bartram, and Old Mazey at St. Crux

A sudden thump on the outside of the door, followed by one mighty bark from each of the dogs, had made Magdalen start. “Come in!” shouted the admiral. The door opened; the tails of Brutus and Cassius cheerfully thumped the floor; and old Mazey marched straight up to the right-hand side of his master’s chair. The veteran stood there, with his legs wide apart and his balance carefully adjusted, as if the dining-room had been a cabin, and the house a ship pitching in a sea-way.

The admiral filled the large glass with port, filled his own glass with claret, and raised it to his lips.

“God bless the Queen, Mazey,” said the admiral.

“God bless the Queen, your honor,” said old Mazey, swallowing his port, as the dogs swallowed the made-dishes, at a gulp.

“How’s the wind, Mazey?”

“West and by Noathe, your honor.”

“Any report to-night, Mazey!”

“No report, your honor.” [“The Seventh Scene — St. Crux-in-the-Marsh,” Chapter I: p. 798 in serial p. 239 in volume]

Vignette Illustration: Magdalen with the Admiral’s dogs, Brutus and Cassius

Magdalen only knew how she had felt the small malice of the female servants, by the effect which the rough kindness of the old sailor produced on her afterward. The dumb welcome of the dogs, when the movements in the room had roused them from their sleep, touched her more acutely still. Brutus pushed his mighty muzzle companionably into her hand; and Cassius laid his friendly fore-paw on her lap. Her heart yearned over the two creatures as she patted and caressed them. It seemed only yesterday since she and the dogs at Combe-Raven had roamed the garden together, and had idled away the summer mornings luxuriously on the shady lawn. [“The Seventh Scene — St. Crux-in-the-Marsh,” Chapter I: p. 798 in serial p. 240 in volume]

Commentary on the Illustrations: Magdalen’s machinations at St. Crux-in-the-Marsh

The scene shifts once again, from Baliol Cottage in Scotland to Noel Vanstone’s customary retreat, Admiral Bartram’s somewhat dilapidated estate, St. Crux-in-the-Marsh, Essex, in February, 1848. However, Magdalen has not arrived as a lady-visitor, but in disguise as a parlour-maid recently hired for the Admiral, a peculiar old fellow who does not employ any male household servants. The only exception is an “old salt,” Old Mazey, who serves as a sort of companion for the retired Admiral: he is the elderly sailor whom McLennan has included in this scene. She has discovered much about the domestic circumstances at St. Crux from a Mrs. Attwood, servant to the lawyer, Mr. Loscombe, at his offices at Lincoln’s Inn; one of her daughters, a servant at the Admiral’s, is the source of the elderly woman’s considerable knowledge of the Admiral's household:

The only mistress at St. Crux is the housekeeper. But there is a master — Admiral Bartram. He appears to be a strange old man, whose whims and fancies amuse his servants as well as his friends. One of his fancies (the only one we need trouble ourselves to notice) is, that he had men enough about him when he was living at sea, and that now he is living on shore, he will be waited on by women-servants alone. The one man in the house is an old sailor, who has been all his life with his master — he is a kind of pensioner at St. Crux, and has little or nothing to do with the housework. The other servants, indoors, are all women; and instead of a footman to wait on him at dinner, the admiral has a parlor-maid. The parlor-maid now at St. Crux is engaged to be married, and as soon as her master can suit himself she is going away. [“The Sixth Scene — St. John’s Wood,” Chapter II, p. 233 in volume]

Magdalen has had weeks to learn the skills of such a servant in the dining-room and parlour from her own maid, Louisa, for whom she has provided passage to Australia, and a new life with the carpenter who is the father of her illegitimate child. Magdalen has gone to so much trouble learning the necessary skills and acquiring appropriate servant’s dresses, and taken a domestic position so far below her own social station, in order to discover how the letter governing Admiral Bartram’s administering of the will of the late Noel Vanstone dictates the disposition of her inheritance (under what her lawyer has termed a “Secret Trust”). If she can study carefully the specific, limiting terms of the “Secret Trust,” she reasons, she can prevent the Admiral’s nephew, George, from inheriting the Combe-Raven estate (unbeknownst to Magdalen, her own sister has developed a romantic relationship with this heir apparent). The reader is already acquainted with the terms of this trust or letter, designed of course to prevent George’s falling prey to Magdalen’s machinations.

Left: McLennan’s vignette of the old sea-dog for “The Fourth Scene — Aldborough, Suffolk.” Chapter XII.

Magdalen’s status as a servant is signalled in both the smaller and the larger wood-engravings by her head-dress and gown, both sewn by and modelled on those of her own servant, Louisa (whose name and identity Magdalen has appropriated). In the main plate, she serves the Admiral and his quirky pensioner their after-dinner glass of port. Magdalen’s relationship with the Admiral’s over-sized Labradors (whom McLennan has rendered as mastiffs) reminds readers of her true social status and privileged upbringing at Combe-Raven, and underscores her rejection by the other female servants, perhaps because, as the old sea-dog speculates, she is far more beautiful. The model ship behind her in the vignette reminds readers of Collins’s having already introduced the Admiral’s pensioner in a previous vignette of a “weather-beaten old man-servant” in the 4 October 1862 serial number.

Image scans and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Blain, Virginia. “Introduction” and “Explanatory Notes” to Wilkie Collins’s No Name. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.