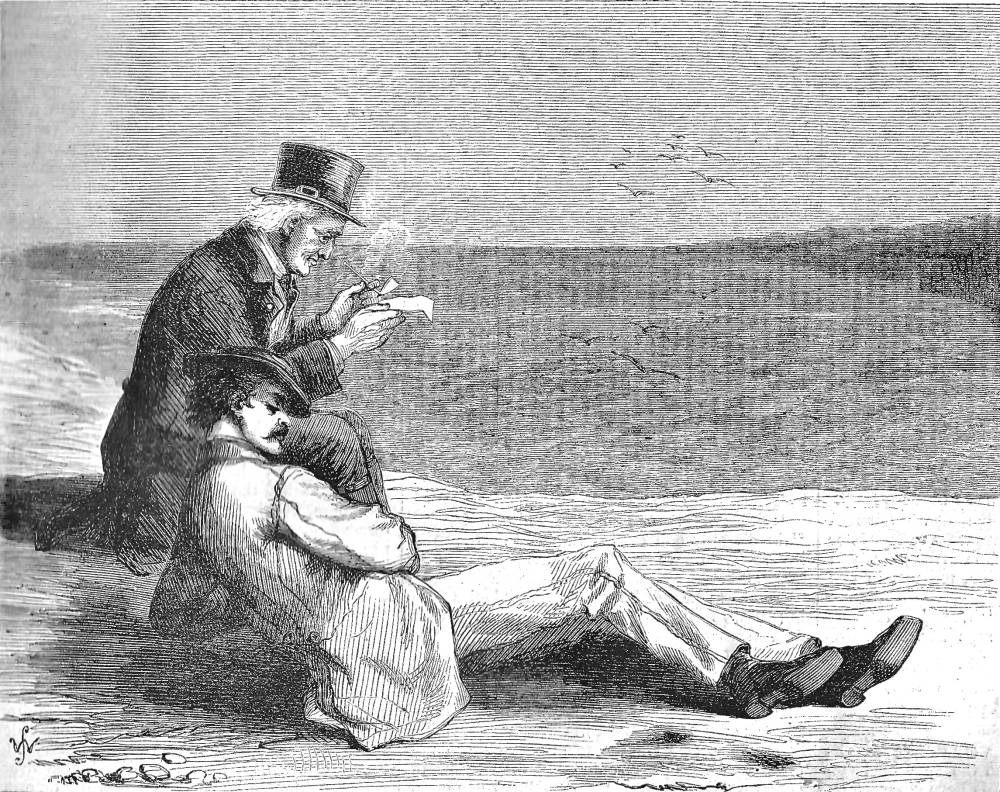

William Jewett's He gave me the extract from the Colonel's will. — second illustration for the Harper's Weekly serialisation of The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins (18 January 1868; third weekly instalment), Chapter VI in "First Period. The Loss of the Diamond (1848), The Events related by Gabriel Betteredge," p. 37. 11.5 x 14.5 cm. (5 ⅝ by 4 ⅝ inches), p. 37; p. 28 in volume. Having called Rosanna Spearman for dinner from the dunes overlooking the Shivering Sands, Gabriel Betteredge now encounters Franklin Blake, arrived early. The pair consider the implications of the extract from Herncastle's will pertaining to the gift of the diamond, which he has just brought with him from London. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

The illustrations appearing here are courtesy of the E. J. Pratt Fine Arts Library, University of Toronto, and the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia.

Passage Illustrated

We looked at each other, and then we looked at the tide, oozing in smoothly, higher and higher, over the Shivering Sand.

"What are you thinking of?" says Mr. Franklin, suddenly.

"I was thinking, sir," I answered, "that I should like to shy the Diamond into the quicksand, and settle the question in that way."

"If you have got the value of the stone in your pocket," answered Mr. Franklin, "say so, Betteredge, and in it goes!"

It's curious to note, when your mind's anxious, how very far in the way of relief a very small joke will go. We found a fund of merriment, at the time, in the notion of making away with Miss Rachel's lawful property, and getting Mr. Blake, as executor, into dreadful trouble — though where the merriment was, I am quite at a loss to discover now.

Mr. Franklin was the first to bring the talk back to the talk's proper purpose. He took an envelope out of his pocket, opened it, and handed to me the paper inside.

"Betteredge," he said, "we must face the question of the Colonel's motive in leaving this legacy to his niece, for my aunt's sake. Bear in mind how Lady Verinder treated her brother from the time when he returned to England, to the time when he told you he should remember his niece's birthday. And read that."

He gave me the extract from the Colonel's Will. I have got it by me while I write these words; and I copy it, as follows, for your benefit:

"Thirdly, and lastly, I give and bequeath to my niece, Rachel Verinder, daughter and only child of my sister, Julia Verinder, widow — if her mother, the said Julia Verinder, shall be living on the said Rachel Verinder's next Birthday after my death — the yellow Diamond belonging to me, and known in the East by the name of The Moonstone: subject to this condition, that her mother, the said Julia Verinder, shall be living at the time. And I hereby desire my executor to give my Diamond, either by his own hands or by the hands of some trustworthy representative whom he shall appoint, into the personal possession of my said niece Rachel, on her next birthday after my death, and in the presence, if possible, of my sister, the said Julia Verinder. And I desire that my said sister may be informed, by means of a true copy of this, the third and last clause of my Will, that I give the Diamond to her daughter Rachel, in token of my free forgiveness of the injury which her conduct towards me has been the means of inflicting on my reputation in my lifetime; and especially in proof that I pardon, as becomes a dying man, the insult offered to me as an officer and a gentleman, when her servant, by her orders, closed the door of her house against me, on the occasion of her daughter's birthday." [Chapter VI in "The First Period. The Loss of the Diamond (1848)," Part Three, 18 January 1868, p. 38 (second page of the instalment); p. 28 in volume]

Commentary

In order to prevent the Indians' taking his life to dislodge the diamond from safe-keeping and subsequently steal it (that is, regain possession of it, since Herncastle himself had stolen it as spoils of war), Herncastle has determined that, should he die of unnatural causes or disappear, the Moonstone should lose its efficacy as a sacred object by being cut up into four to six smaller gemstones in Amsterdam. These and the remaining terms of the will Franklin Blake (whose father had agreed to be Herncastle's executor) and Gabriel Betteredge discuss far from where they might be overheard — down on the Yorkshire seashore near the Shivering Sands. This eighth illustration therefore reprises a significant character, the narrator Gabriel Betteredge, brings on stage the male ingénue, and uses as its backdrop one of the novel's chief settings which has both atmospheric effect and psychological import.

Herncastle's death six months earlier has precipitated the crisis since, under the terms of his will, his niece, Rachel Verinder, is to receive the Moonstone as a gift for her eighteenth birthday, in about a month's time. Gabriel Betteredge and Franklin Blake try to determine whether they gift is a token of repentance (as the clergyman's letter that informed Julia Verinder of her brother's death intimates) or whether it is his way of punishing his sister by bringing down the curse of the Moonstone upon his sister's family. To forestall some attempt by the Indians to re-acquire the jewel, Franklin Blake determines to ride over to the bank at Frizinghall and deposit it until it will be needed on Rachel's eighteenth birthday, on 21 June 1848.

The three January 18th illustrations, taken together, underscore the importance of the terms of the will, and also indicate in the headnote vignette that Franklin Blake (seen riding a horse, presumably to Frizinghall) will transfer the gem to a bank rather than retain on his person or in his room. Whereas the first instalment introduced only Herncastle and the Brahmin guardians of the Moonstone, the second instalment (January 11) introduced the Verinders' trusted family retainer, Gabriel Betteredge (seen in both the headnote vignette and one of the two regular illustrations); Colonel Herncastle, no longer young or in uniform, appears with the butler; and by herself on the seashore the reader encounters the enigmatic figure of the reformed criminal Rosanna Spearman. The third instalment (18 January 1868) introduces the story's male protagonist, Franklin Blake, both in the headnote vignette as a solitary rider and in the first of the two main illustrations, with Gabriel Betteredge. Although the third illustration is of a scene which occurred months earlier, when Herncastle was dictating his will, it is introduced significantly as a flashback — after the scene at the dunes in which the butler and the Verinder cousin discuss the terms of that will, so that the order of the illustrations duplicates the disruption in linear time that one finds in the accompanying text. Although in this, the first rectangular full-size wood-engraving of the series, Franklin Blake seems an indolent and even listless, fashionably dressed young bourgeois, the illustrator conveys his more active and decisive nature through the headnote vignette, which again presents an event that occurs after rather than before the second illustration, contributing to the complicated, forward-backward movement of the Collinsian narrative.

Similar self-reflexivity appears in the linked illustrations to Part 3, which depict Herncastle making his will and Franklin and Betteredge reading its clauses after his death — Leighton and Surridge, p. 224.

Franklin Blake's Facial Hair in Various Editions (1868 to 1910)

The beardless Franklin Blake of the introductory illustrations in instalment three of Harper's Weekly, (notably "He gave me the extract from the Colonel's will" in Chapter 6) is interpreted very differently by A. E. Fraser and Alfred Pearse simply because, unlike William Jewett and the second American illustrator who contributed to Harper's Weekly, these later British illustrators had already read the subsequent description of Franklin Blake on Rachel's eighteenth birthday: while smooth-faced Godfrey Ablewhite and his sisters respond excitedly to the alluring yellow diamond, Blake is "stroking his beard" pensively, wondering if Julia Verinder will consider the gift in the same light as he has construed it — not a gift, but a punishment for recent rejection of him. By the time that the American illustrators executed the later scenes, they must have known that Collins had described Blake as bearded, the style for upper-class young men after the Crimean War; however, it was too late to adjust the image and provide him with a beard, and so for purposes of visual continuity Franklin Blake had to stay beardless for the remainder of the serial. They should have realized from the painting scene in the fourth instalment (Chapter 8) onward that they had erred in giving Blake only a moustache, an impossibility if he is "tugging at his beard, and looking anxiously towards the window" at Lady Julia Verinder (Chapter 9, p. 54). Incidental as the matter of Franklin Blake's facial hair may seem, it underscores the problems in interpreting these transatlantic illustrations since they do not necessarily represent a true collaboration of author and illustrator. Collins's approval after the fact is hardly evidence that they represent authorial intention, even though the sixty-six illustrations are generally successful as complements to the letterpress. Betteredge's being depicted in livery is an obvious case in point, since Collins noted in his letter to Harper's that an English butler should not be so costumed.

Related Material

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- George Du Maurier, "Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?" — p. 94.

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- 1910 Frontispiece: "He felt himself suddenly seized round the neck." Page 279.

- The 1944 Illustrations by William Sharp for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone

- Gallery of Headnote Vignettes by William Jewett for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone in Harper's Weekly (4 January — 8 August 1868)

Bibliography

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. With sixty-six illustrations by William Jewett. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Vol. 12 (1868), 4 January through 8 August 1868, pp. 5-529.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. All the Year Round. 1 January-8 August 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by William Jewett. New York: Harper & Bros., 1871.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by George Du Maurier and F. A. Fraser. London: Chatto and Windus, 1890.

_________. The Moonstone, Parts One and Two. The Works of Wilkie Collins, vols. 5 and 6. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1900.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by A. S. Pearse. London & Glasgow: Collins, 1910, rpt. 1930.

_________. The Moonstone. Illustrated by William Sharp. New York: Doubleday, 1946.

Karl, Frederick R. "Introduction." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Scarborough, Ontario: Signet, 1984. Pp. 1-21.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review Volume 42, Number 3 (Fall 2009): pp. 207-243. Accessed 1 July 2016. http://englishnovel2.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/files/2014/01/42.3.leighton-moonstone-serializatation.pdf

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, & Victorian Authorship. London and Ithaca, NY: Cornll U. P., 2001.

Peters, Catherine. The King of the Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. London: Minerva, 1991.

Reed, John R. "English Imperialism and the Unacknowledged crime of The Moonstone. Clio 2, 3 (June, 1973): 281-290.

Stewart, J. I. M. "A Note on Sources." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 527-8.

Vann, J. Don. "The Moonstone in All the Year Round, 4 January-8 1868." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 48-50.

Winter, William. "Wilkie Collins." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 203-219.

Created 7 August 2016

Last modified 29 October 2025