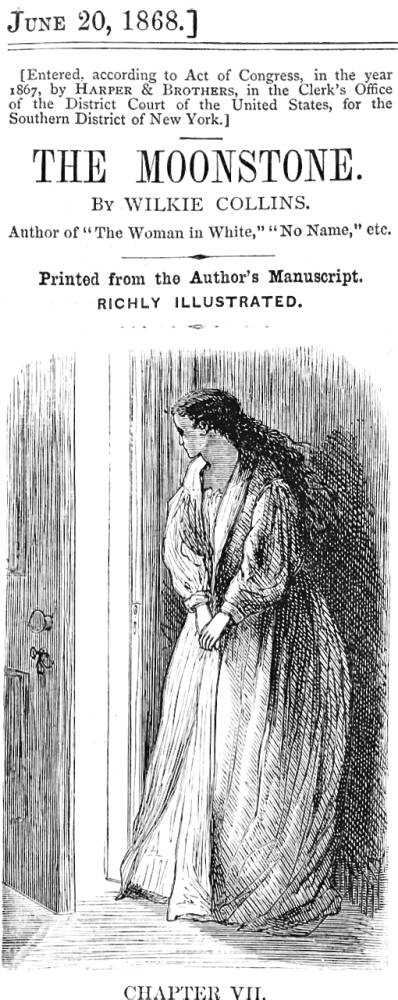

[Rachel Verinder at the door of her bedroom, on the night of her birthday, watching something going on in her sitting-room] — Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance: "Second Period, Third Narrative, Contributed by Franklin Blake," uncaptioned headnote vignette for Chapter VII, the twenty-third such vignette. The twenty-fifth instalment in Harper's Weekly (20 June 1868), page 389. Wood-engraving, 9.1 x 5.7 cm., located at the head of the seventh chapter in the first volume edition, p. 168. [The Harper & Bros. house illustrator focuses on the cause of Rachel Verinder's obstructionist behaviour after the theft of the Moonstone, as she, like the housemaid Rosanna Spearman, tried to protect the man whom she loved.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. Illustrations courtesy of the E. J. Pratt Fine Arts Library, University of Toronto, and the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Universities of Toronto and British Columbia and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite The Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage suggested by the Headnote Vignette for the Twenty-fifth Instalment

"I want to ask you something," I said. "I want you to tell me everything that happened, from the time when we wished each other good night, to the time when you saw me take the Diamond."

She lifted her head from my shoulder, and made an effort to release her hand. "Oh, why go back to it!" she said. "Why go back to it!"

"I will tell you why, Rachel. You are the victim, and I am the victim, of some monstrous delusion which has worn the mask of truth. If we look at what happened on the night of your birthday together, we may end in understanding each other yet."

Her head dropped back on my shoulder. The tears gathered in her eyes, and fell slowly over her cheeks. "Oh!" she said, "have I never had that hope? Have I not tried to see it, as you are trying now?"

"You have tried by yourself," I answered. "You have not tried with me to help you."

Those words seemed to awaken in her something of the hope which I felt myself when I uttered them. She replied to my questions with more than docility — she exerted her intelligence; she willingly opened her whole mind to me.

"Let us begin," I said, "with what happened after we had wished each other good night. Did you go to bed? or did you sit up?"

"I went to bed."

"Did you notice the time? Was it late?"

"Not very. About twelve o'clock, I think."

"Did you fall asleep?"

"No. I couldn't sleep that night."

"You were restless?"

"I was thinking of you."

The answer almost unmanned me. Something in the tone, even more than in the words, went straight to my heart. It was only after pausing a little first that I was able to go on.

"Had you any light in your room?" I asked.

"None — until I got up again, and lit my candle."

"How long was that, after you had gone to bed?"

"About an hour after, I think. About one o'clock."

"Did you leave your bedroom?"

"I was going to leave it. I had put on my dressing-gown; and I was going into my sitting-room to get a book — —"

"Had you opened your bedroom door?"

"I had just opened it."

"But you had not gone into the sitting-room?"

"No — I was stopped from going into it."

"What stopped you?"

"I saw a light, under the door; and I heard footsteps approaching it."

"Were you frightened?"

"Not then. I knew my poor mother was a bad sleeper; and I remembered that she had tried hard, that evening, to persuade me to let her take charge of my Diamond. She was unreasonably anxious about it, as I thought; and I fancied she was coming to me to see if I was in bed, and to speak to me about the Diamond again, if she found that I was up."

"What did you do?"

"I blew out my candle, so that she might think I was in bed. I was unreasonable, on my side — I was determined to keep my Diamond in the place of my own choosing."

"After blowing out the candle, did you go back to bed?"

"I had no time to go back. At the moment when I blew the candle out, the sitting-room door opened, and I saw ——"

"You saw?"

"You."

"Dressed as usual?"

"No."

"In my nightgown?"

"In your nightgown — with your bedroom candle in your hand."

"Alone?"

"Alone."

"Could you see my face?"

"Yes."

"Plainly?"

"Quite plainly. The candle in your hand showed it to me."

"Were my eyes open?"

"Yes."

"Did you notice anything strange in them? Anything like a fixed, vacant expression?"

"Nothing of the sort. Your eyes were bright — brighter than usual. You looked about in the room, as if you knew you were where you ought not to be, and as if you were afraid of being found out."

"Did you observe one thing when I came into the room — did you observe how I walked?"

"You walked as you always do. You came in as far as the middle of the room — and then you stopped and looked about you."

"What did you do, on first seeing me?"

"I could do nothing. I was petrified. I couldn't speak, I couldn't call out, I couldn't even move to shut my door."

"Could I see you, where you stood?"

"You might certainly have seen me. But you never looked towards me. It's useless to ask the question. I am sure you never saw me."

"How are you sure?" — "Second Period, Third Narrative,Contributed by Franklin Blake," Chapter 7, p. 389.

Commentary

The Harper's illustrators also repeatedly deploy threshold settings, locating Collins’s characters near doors or windows. These thresholds, we argue, visually suggest the sensation genre's propensity for disrupting boundaries of gender and class, as well as this particular novel's violation of barriers between the known and the unknown, white and nonwhite, England and its foreign others, law and desire, the conscious and the unconscious. The illustrations show Rachel watching the man she loves steal her gemstone (chapter head, Part 25); Rachel watching the investigation and wishing that Franklin might escape (Part 6, fig. 7); and Franklin sleepwalking, midway between conscious and unconscious states (chapter head, Part 30). All of these events place characters in positions where their conscious ethics and their basic drives collide, suggesting how the novel presses beyond the surface of identity, probing its margins. The illustrations contribute, then, to the novel’s status as sensation fiction, suggesting the text's roiling undercurrents, its deep-set fears of colonial invasion at the heart of England, and its capacity to undermine or cross boundaries fundamental to self and social identities.— Surridge and Leighton, p. 222.

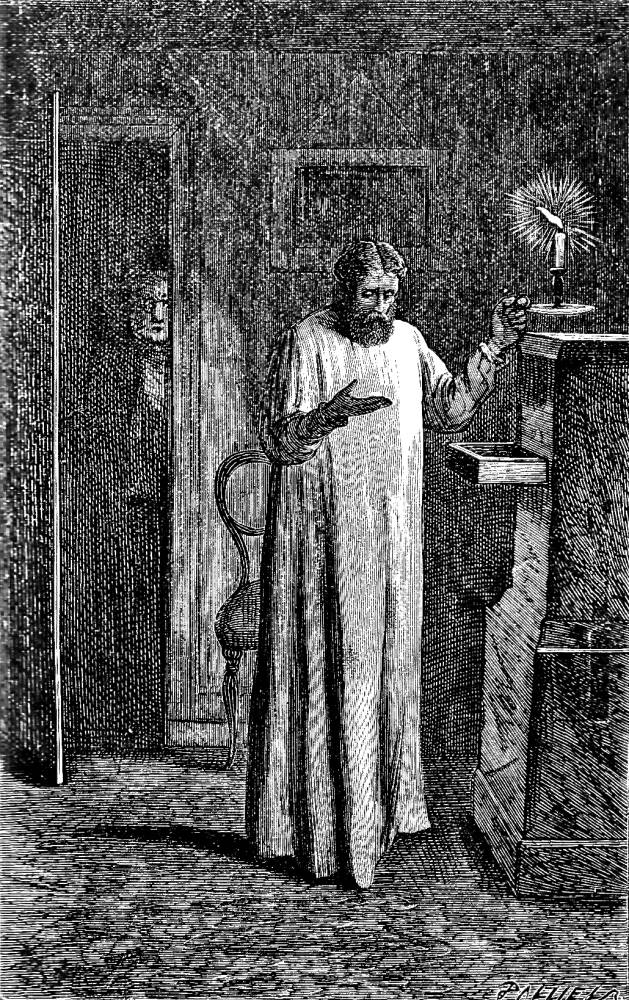

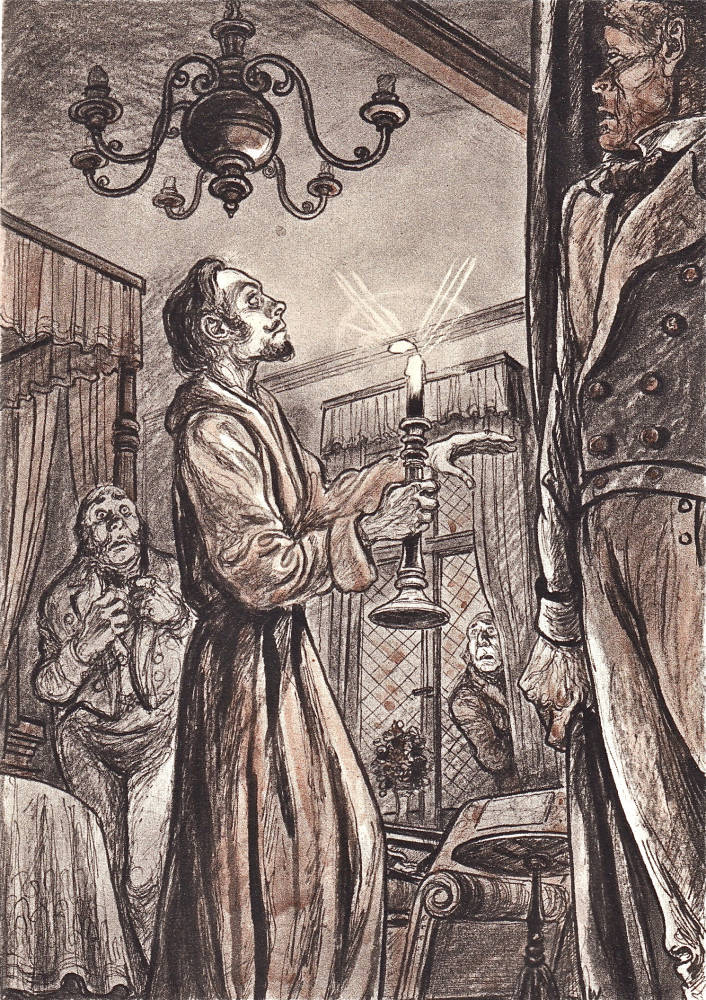

The serial instalment for 25 July 1868 uses the headnote vignette to describe Franklin Blake's sleepwalking under the influence of the slightly enlarged dose of laudanum administered by Ezra Jennings, but does not show his opening the cabinet to move the Moonstone. In the headnote vignette for 20 June 1868, the illustrators depict Rachel in her nightgown, presumably watching awestruck as Franklin Blake takes the Moonstone from her cabinet; the theft itself is not shown. The latter thumbnail is, of course, a flashback, so that its appearance on the same page as the interview between Franklin Blake and Rachel Verinder a year later in Mr. Bruff's conservatory severely disrupts the story's linear flow, forcing the reader to ponder its meaning at the head of the twenty-fifth weekly instalment. Blake asks Rachel not merely to remember, but to critique her memory of the events of 21-22 June 1848 to solve the riddle of how she saw him do something of which he has absolutely no recollection.

The small-scale illustration clearly shows the theshold, and the illumination of the front of Rachel's nightgown implies the presence of Franklin Blake's candle in the room to the left.

Relevant Chatto and Windus Edition (1890) and Collins Clear-type Edition (1910) Illustrations

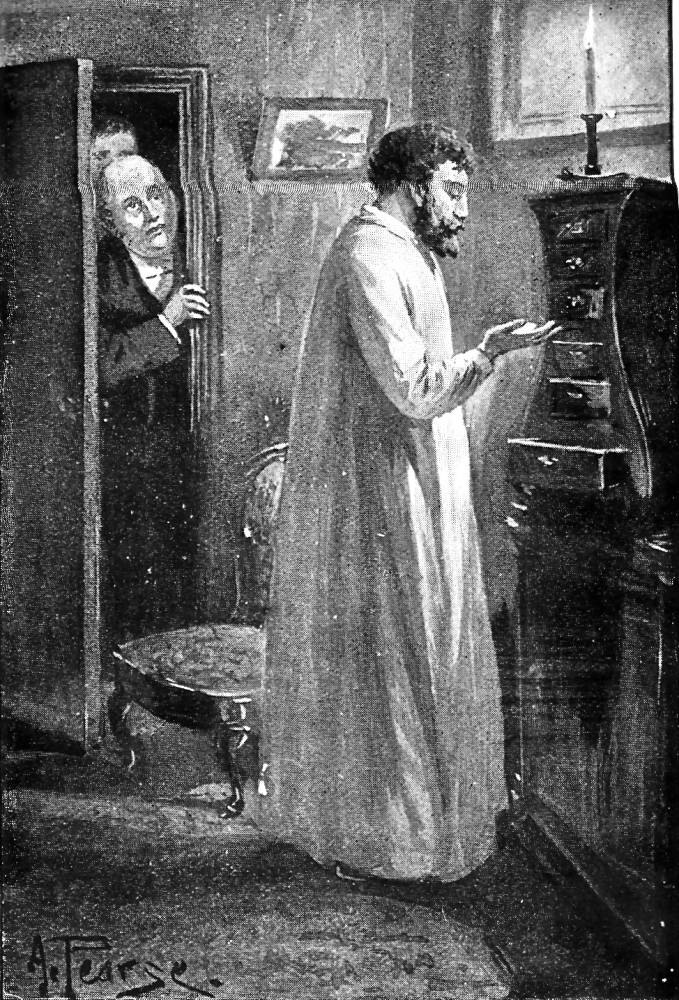

Left: F. A. Fraser's realisation of Franklin Blake's taking the substitute Moonstone under the influence of laudanum, "He took the mock Diamond out with his right hand." (1890). Centre: Alfred Rearse's recapitulation of the 1890 illustration, "He took the Diamond." (1910). Right: William Sharp's illustration of the reconstructed crime-scene, Franklin Blake sleepwalking (uncaptioned, 1944). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Related Materials

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- Illustrations by Alfred Pearse for The Moonstone: A Romance (1910)

- The 1944 illustrations by William Sharp for The Moonstone (1946).

Last updated 1 December 2016