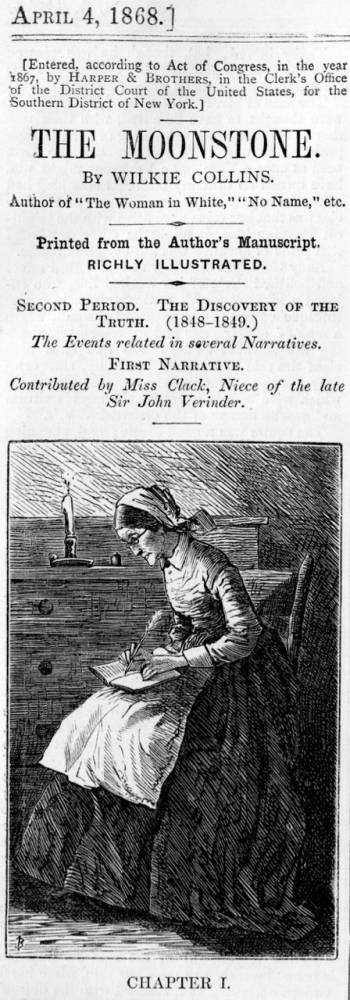

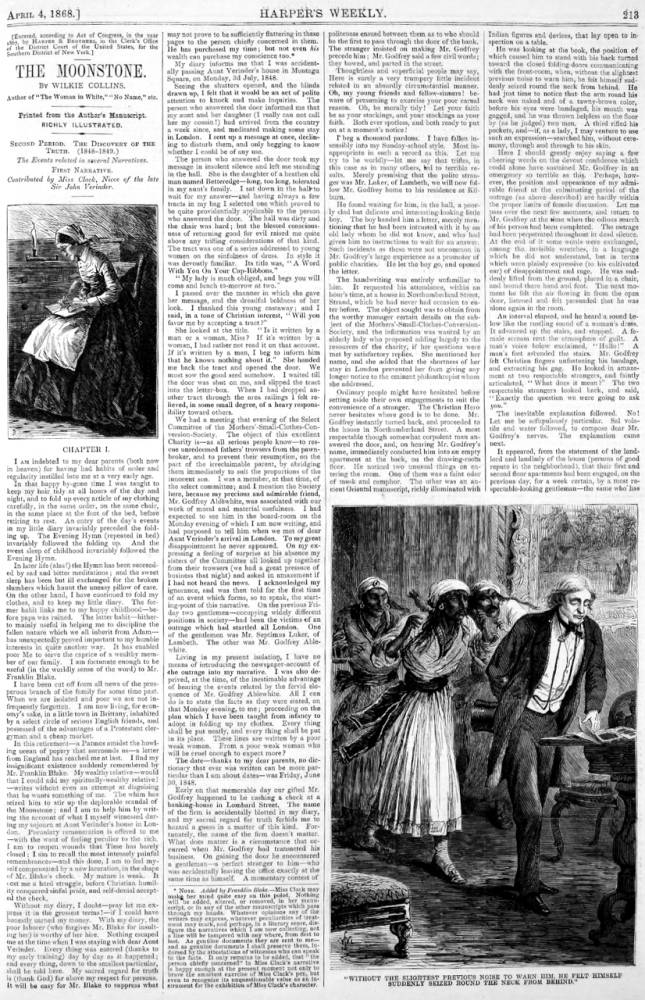

Uncaptioned headnote vignette for the "Second Period. The Discovery of the Truth. (1848-1849.) The Events related in several Narratives. First Narrative. Contributed by Miss Clack, Niece of the late Sir John Verinder." Chapter 1 — initial illustration for the fourteenth instalment in Harper's Weekly (4 April 1868), page 213. Wood-engraving, 8.7 x 5.6 cm. [In the fourteenth headnote vignette, the Harper & Bros. house illustrator "C. B." presents the second major narrator, Miss Clack. Commissioned to do so by Franklin Blake (whose motive she does not clarify), the no more than middle-aged "old" maid is writing in her diary by candle light in order to reconstruct events in London from her perspective after Rachel and Lady Julia have left the family estate in Yorkshire. Ironically, the self-absorbed Miss Clack, the Verinders' poor relation, honestly believes that "Nothing escaped [her] at the time when [she] was staying with dear Aunt Verinder."]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Illustrations courtesy of the E. J. Pratt Fine Arts Library, University of Toronto, and the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia.

Passage Suggested by the Headnote Vignette: Miss Clack Writing in her Diary

I have been cut off from all news of my relatives by marriage for some time past. When we are isolated and poor, we are not infrequently forgotten. I am now living, for economy's sake, in a little town in Brittany, inhabited by a select circle of serious English friends, and possessed of the inestimable advantages of a Protestant clergyman and a cheap market.

In this retirement — a Patmos amid the howling ocean of popery that surrounds us — a letter from England has reached me at last. I find my insignificant existence suddenly remembered by Mr. Franklin Blake. My wealthy relative — would that I could add my spiritually-wealthy relative! — writes, without even an attempt at disguising that he wants something of me. The whim has seized him to stir up the deplorable scandal of the Moonstone: and I am to help him by writing the account of what I myself witnessed while visiting at Aunt Verinder's house in London. Pecuniary remuneration is offered to me — with the want of feeling peculiar to the rich. I am to re-open wounds that Time has barely closed; I am to recall the most intensely painful remembrances — and this done, I am to feel myself compensated by a new laceration, in the shape of Mr. Blake's cheque. My nature is weak. It cost me a hard struggle, before Christian humility conquered sinful pride, and self-denial accepted the cheque.

Without my diary, I doubt — pray let me express it in the grossest terms! — if I could have honestly earned my money. With my diary, the poor labourer (who forgives Mr. Blake for insulting her) is worthy of her hire. Nothing escaped me at the time I was visiting dear Aunt Verinder. Everything was entered (thanks to my early training) day by day as it happened; and everything down to the smallest particular, shall be told here. My sacred regard for truth is (thank God) far above my respect for persons. It will be easy for Mr. Blake to suppress what may not prove to be sufficiently flattering in these pages to the person chiefly concerned in them. He has purchased my time, but not even his wealth can purchase my conscience too. — "Second Period. First Narrative," Chapter 1 (4 April 1868), p. 213.

* Note. Added By Franklin Blake. — Miss Clack may make her mind quite easy on this point. Nothing will be added, altered or removed, in her manuscript, or in any of the other manuscripts which pass through my hands. Whatever opinions any of the writers may express, whatever peculiarities of treatment may mark, and perhaps in a literary sense, disfigure the narratives which I am now collecting, not a line will be tampered with anywhere, from first to last. As genuine documents they are sent to me — and as genuine documents I shall preserve them, endorsed by the attestations of witnesses who can speak to the facts. It only remains to be added that "the person chiefly concerned" in Miss Clack's narrative, is happy enough at the present moment, not only to brave the smartest exercise of Miss Clack's pen, but even to recognise its unquestionable value as an instrument for the exhibition of Miss Clack's character.

Commentary: The Imperceptive Narrator

In his second preface for the novel (one that is not often reprinted), Wilkie Collins noted the popularity of Miss Clack with his transatlantic readership, suggesting that she was viewed as comic relief for her tendency to impose her religious views upon others and her inability to understand the events she records, even though she scrupulously consults her diary (as in the Harper's Weekly uncaptioned headnote vignette for 4 April 1868) and is even able to indicate the precise date on which her "Christian Hero" was mugged by Hindu ruffians (Friday, 30 June, 1848). As Collins remarks,

My good readers in England and America, whom I had never yet disappointed, were expecting their regular weekly instalments of the new story. I held to the story — for my own sake as well as for theirs. In the intervals of grief [at the death of the novelist's mother], in the occasional remissions of pain, I dictated from my bed that portion of The Moonstone which has since proved most successful in amusing the public — the "Narrative of Miss Clack." — "Preface to a New Edition," May 1871.

Miss Drusilla Clack, the niece of Sir John Verinder, is — as a result of her late father's bankruptcy, a poor relation of the Verinders. "Secure in the deep sense of her own rectitude" (Marshall 81), Drusilla Clack represents partial understanding and considerable fundametalist bias, both against foreigners in general and Catholics in particular, and against frivolous and beautiful young women. Apparently unaware of the conclusion of the story to which she is contributing, she makes no bones about her bias in favour of Godfrey Ablewhite, whom she styles a "Christian hero"; indeed, the reader recognizes her romantic infatuation amounting to hero worship of her gifted and charitably inclined cousin, whose egocentrism and hypocrisy she fails to detect. Thus, she is an obtuse and unreliable first-person narrator whose objective record-keeping is accurate, but whose assessments of the motives of other characters are fundamentally flawed. She is, then, something of a caricature of pious, judgmental, unpleasant old maid whom we, along with Penelope Betteredge, judge to be a fawning parasite in the company of Lady Julia Verinder, even as she unconsciously reveals her jealousy of the privileged Rachel Verinder. Miss Clack "fasten[s] herself on" Lady Verinder whenever her wealthy, titled relatives visit London. Gabriel Betteredge on the night of the birthday party notes Miss Clack's capacity for champagne, in spite of her Temperance pamphlets and leadership in the Small-Clothes Society. In his preface, Collins defends his use of such an exaggerated character type as one of his seven narrators, among the "family voices" of which Miss Clack's is markedly antiphonal and ironically comic. In reading her "account" one is invited to accept what she says at face value then critique and interrogate it in light of her prejudices, which she exhibits even when, after the events that she reports, she must know that her beloved Godfrey was the one who stole the Moonstone.

Hers is hardly a euphonious name since "clack" means "making a mindless, repetitive noise" (like a hen's clucking) and "Drusilla" (never a popular name) is the the name that belonged to Caligula's sister. Although this hardly amounts to name symbolism, Collins has chosen an unpleasant-sounding name for his least pleasant narrator. Since has, apparently, gone abroad before the Moonstone mystery is resolved, and is out of contact with her extended family, for she has gone is further than Calais, the French port city chosen by impoverished nobility as a place of residence not too far from home. She expresses disgust for the "little town in Brittany" because it marks her family's financial failure and for her is aplace of economic exile. The phrase "howling ocean of popery" implies that Miss Clack is living in a conservative, Catholic community at odds with her peculiar brand of Protestant fundamentalism — and obviously a bit off the beaten track since her mail service is infrequent. Wherever she may be, the American illustrator shows her consulting her diary to reconstruct events in the first chapter of the second period, 1848-1849.

Related Material

- "The Moonstone" and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in "The Moonstone"

- George Du Maurier, "Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?" — p. 94.

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's "The Moonstone: A Romance" (1890)

- 1910 Frontispiece: "He felt himself suddenly seized round the neck." Page 279.

Last updated 27 November 2016