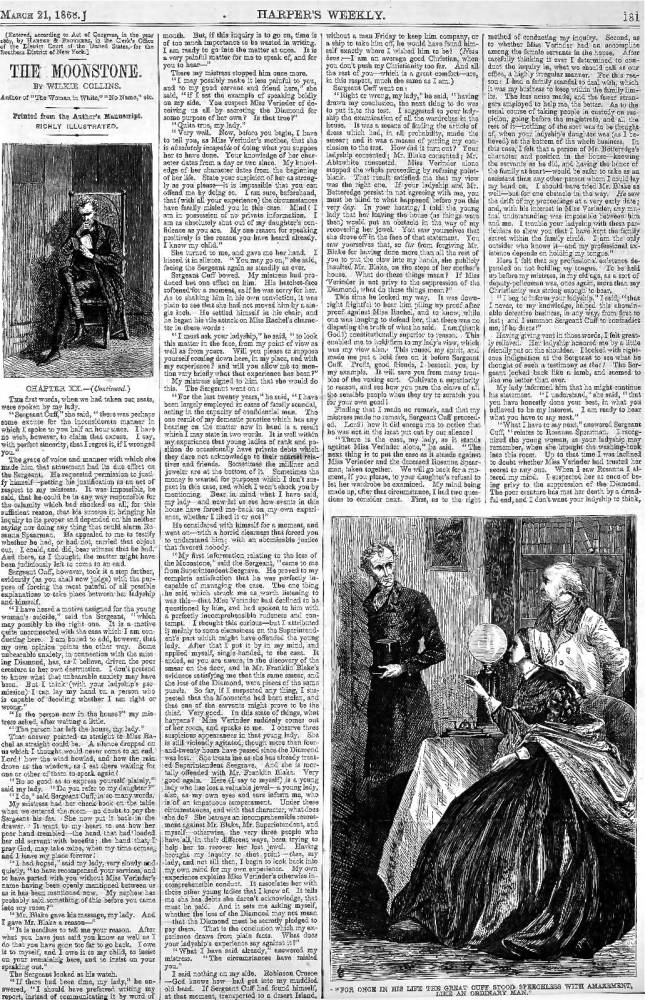

Uncaptioned headnote vignette for "First Period: The Loss of the Diamond (1848), The Events related by Gabriel Betteredge, house-steward in the service of Julia, Lady Verinder." Chapter 20 — initial illustration for the twelfth instalment in Harper's Weekly (21 March 1868), p. 181. Wood-engraving, 8.5 x 5.4 cm. [In the twelfth headnote vignette, the Harper & Bros. house illustrators "C. B." and "W. J." (William Jewett) present the scene in which Sergeant Cuff contemplates the railway schedule after receiving his dismissal from Lady Julia, who is more interested in protecting her daughter than in recovering the Moonstone — her malignant brother's dubious birthday gift to Rachel.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. Illustrations courtesy of the E. J. Pratt Fine Arts Library, University of Toronto, and the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Universities of Toronto and British Columbia and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite The Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage suggested by the Headnote Vignette for the Twelfth Instalment

People in high life have all the luxuries to themselves — among others, the luxury of indulging their feelings. People in low life have no such privilege. Necessity, which spares our betters, has no pity on us. We learn to put our feelings back into ourselves, and to jog on with our duties as patiently as may be. I don't complain of this — I only notice it. Penelope and I were ready for the Sergeant, as soon as the Sergeant was ready on his side. Asked if she knew what had led her fellow-servant to destroy herself, my daughter answered (as you will foresee) that it was for love of Mr. Franklin Blake. Asked next, if she had mentioned this notion of hers to any other person, Penelope answered, "I have not mentioned it, for Rosanna's sake." I felt it necessary to add a word to this. I said, "And for Mr. Franklin's sake, my dear, as well. If Rosanna has died for love of him, it is not with his knowledge or by his fault. Let him leave the house to-day, if he does leave it, without the useless pain of knowing the truth." Sergeant Cuff said, "Quite right," and fell silent again; comparing Penelope's notion (as it seemed to me) with some other notion of his own which he kept to himself.

At the end of the half-hour, my mistress's bell rang.

On my way to answer it, I met Mr. Franklin coming out of his aunt's sitting-room. He mentioned that her ladyship was ready to see Sergeant Cuff — in my presence as before — and he added that he himself wanted to say two words to the Sergeant first. On our way back to my room, he stopped, and looked at the railway time-table in the hall.

"Are you really going to leave us, sir?" I asked. "Miss Rachel will surely come right again, if you only give her time?"

"She will come right again," answered Mr. Franklin, "when she hears that I have gone away, and that she will see me no more." — "First Period: The Loss of the Diamond (1848), The Events related by Gabriel Betteredge, house-steward in the service of Julia, Lady Verinder," Chapter 20, p. 181.

Commentary

The headnote vignette contains yet another figure reading and/or writing, reflecting the activity of the Harper's Weekly subscriber when he or she is reading instrumentally or efferently, that is, for information rather than aesthetic enjoyment. But, whereas Cuff is constantly reading people's facial experessions and the environment for meaningful clues, the reader of Harper's Weekly may indulge in an aesthetic experience of fiction texts and artistic images in the weekly magazine. Here, Sergeant Cuff reads the railway timetable in the hall outside Julia Verinder's sitting-room.

Heightening this motif of interpretation, the Harper's illustrations also call attention to acts of reading. This visual pattern underlines the letterpress’s focus on the interpretation of narrative, the "battle over whose perspective and voice" prevail in the novel. In a series of repetitive images, the illustrations show Cuff, then both Blake and Jennings, all reading (Part 12; Part 28, fig. 8). These scenes of characters immersed in books create self-reflexivity around the reading process itself, reminding us forcefully that The Moonstone requires its characters as well as its readers to become active analysers of narratives, their biases, and visual as well as verbal points of view. — Leighton and Surridge, p. 224.

The celebrated Scotland Yard detective, having been given his dismissal by Lady Julia Verinder because his "theory of the crime" focusses on her daughter as the thief, settles down in an armchair in the hallway to consult the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway's posted schedule (apparently in a book). Collins would have checked his background details scrupulously, and would have discovered such a schedule published by the L & YR (incorporated in 1847).

Related Material

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- Illustrations by Alfred Pearse for The Moonstone: A Romance (1910)

- The 1944 illustrations by William Sharp for The Moonstone (1946).

Last updated 27 November 2016