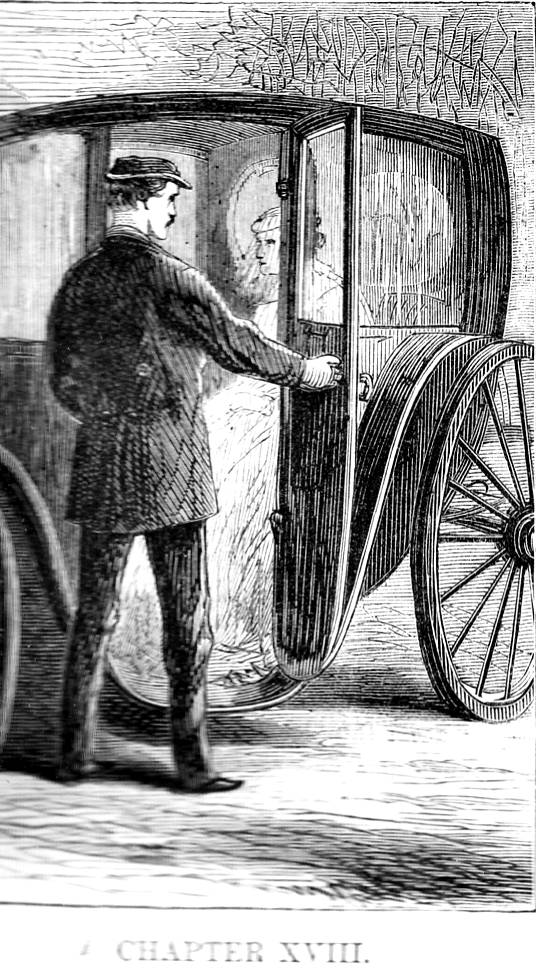

Uncaptioned headnote vignette for "First Period: The Loss of the Diamond (1848), The Events related by Gabriel Betteredge, house-steward in the service of Julia, Lady Verinder." — initial illustration for the eleventh instalment in Harper's Weekly (14 March 1868), p. 165; p. 80 in volume. Wood-engraving, 8.5 x 5.4 cm. (3 ½ by 2 ¼ inches). [In the eleventh headnote vignette, specifically for Chapter XVIII, the Harper & Bros. house illustrators "C. B." and "W. J." (William Jewett) have presented as the main plate the scene in which Lady Julia reluctantly bids her daughter farewell, knowing that her departure by carriage will frustrate Sergeant Cuff's investigation and make her daughter look complicit in the theft.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL.]

The illustrations appear here by courtesy of the E. J. Pratt Fine Arts Library, University of Toronto, and the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia.

Passage Suggested by the Headnote Vignette for the Eleventh Instalment (Chapter XVIII)

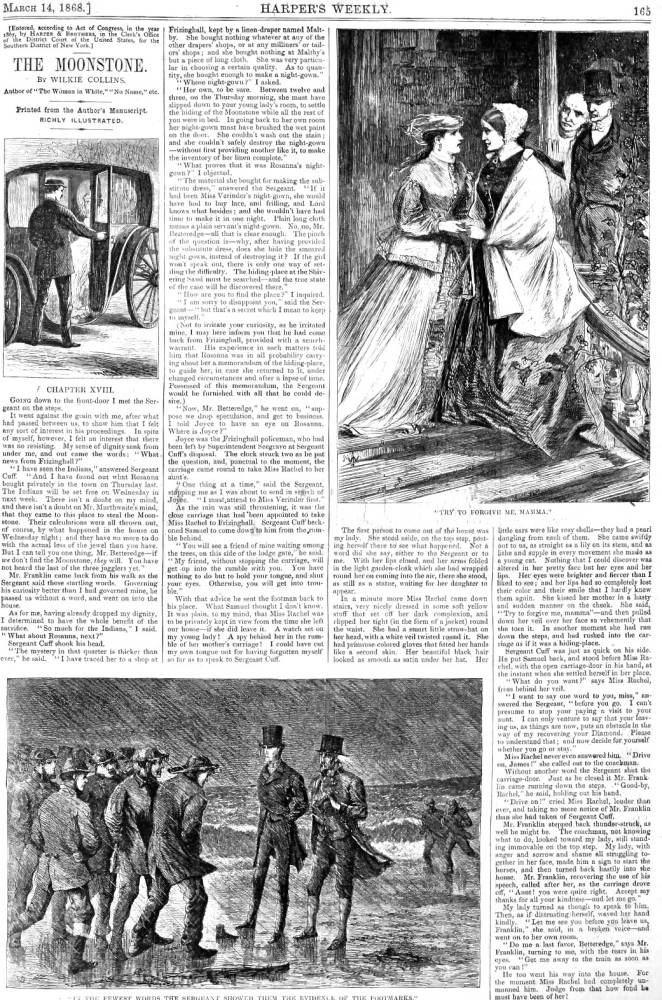

The first person to come out of the house was my lady. She stood aside, on the top step, posting herself there to see what happened. Not a word did she say, either to the Sergeant or to me. With her lips closed, and her arms folded in the light garden cloak which she had wrapped round her on coming into the air, there she stood, as still as a statue, waiting for her daughter to appear.

In a minute more, Miss Rachel came downstairs— very nicely dressed in some soft yellow stuff, that set off her dark complexion, and clipped her tight (in the form of a jacket) round the waist. She had a smart little straw hat on her head, with a white veil twisted round it. She had primrose-coloured gloves that fitted her hands like a second skin. Her beautiful black hair looked as smooth as satin under her hat. Her little ears were like rosy shells — they had a pearl dangling from each of them. She came swiftly out to us, as straight as a lily on its stem, and as lithe and supple in every movement she made as a young cat. Nothing that I could discover was altered in her pretty face, but her eyes and her lips. Her eyes were brighter and fiercer than I liked to see; and her lips had so completely lost their colour and their smile that I hardly knew them again. She kissed her mother in a hasty and sudden manner on the cheek. She said, "Try to forgive me, mamma"— and then pulled down her veil over her face so vehemently that she tore it. In another moment she had run down the steps, and had rushed into the carriage as if it was a hiding-place.

Sergeant Cuff was just as quick on his side. He put Samuel back, and stood before Miss Rachel, with the open carriage-door in his hand, at the instant when she settled herself in her place.

"What do you want?" says Miss Rachel, from behind her veil.

"I want to say one word to you, miss," answered the Sergeant, "before you go. I can't presume to stop your paying a visit to your aunt. I can only venture to say that your leaving us, as things are now, puts an obstacle in the way of my recovering your Diamond. Please to understand that; and now decide for yourself whether you go or stay."

Miss Rachel never even answered him. "Drive on, James!" she called out to the coachman.

Without another word, the Sergeant shut the carriage-door. Just as he closed it, Mr. Franklin came running down the steps. "Good-bye, Rachel," he said, holding out his hand.

"Drive on!" cried Miss Rachel, louder than ever, and taking no more notice of Mr. Franklin than she had taken of Sergeant Cuff.

Mr. Franklin stepped back thunderstruck, as well he might be. The coachman, not knowing what to do, looked towards my lady, still standing immovable on the top step. My lady, with anger and sorrow and shame all struggling together in her face, made him a sign to start the horses, and then turned back hastily into the house. Mr. Franklin, recovering the use of his speech, called after her, as the carriage drove off, "Aunt! you were quite right. Accept my thanks for all your kindness— and let me go."— "First Period: The Loss of the Diamond (1848), The Events related by Gabriel Betteredge, house-steward in the service of Julia, Lady Verinder," Chapter 18, p. 165; p. 81 in volume.

Commentary

Here text and illustration would seem to part company. By the authority of the text, it is Sergeant Cuff and not Franklin Blake who holds the carriage door and closes it for Rachel Verinder, whereas the illustration would lead us to believe (proleptically) that Franklin Blake bids her farewell at the carriage door rather than on the steps. Perhaps he has arrived at the foot of the steps, but he certainly does not open the door that Cuff has just closed. Haughtily (but in fact wounded by what she perceives as Franklin's hypocrisy) Rachel commands her coachman to "drive on." The faint lines in the areas occupied by carriage windows are intended to indicate glass; the spacious vehicle occupied by just that young lady in a glassed-in space suggests both her isolation and her visibility — she is, as a young heiress, under a social microscope.

What strikes the reader as odd about this page containing Chapter XVIII and three illustrations is that these wood-engravings are arrayed in such a way that they are out of chronological order. According to the text, Rachel exits the manor-house and greets her mother at the top of the steps (plate 3, upper right, columns 3-4); she then descends the outside steps, and is handed into her carriage by Sergeant Cuff (not Franklin Blake, as the headnote vignette stipulates (plate 1, upper left, column 1); Betteredge and Cuff, learning from the policeman they have on watch that Rosanna Spearman has slipped out of the house, they then follow her bootprints into the Shivering Sand, and explain their findings to Mr. Yolland and the estate-workers (plate 2, bottom left, columns 1-3, illustrating an incident in the next chapter). The only way to make sense of the trio is to begin in the upper right of the page and proceed counter-clockwise. In other words, the reader has to violate the conventional decoding of the images (a clockwise reading) and rearrange the plates according to what the text actually says. One should not make too much of this violation of chronological sequence as the size of each plate probably dictated where it would have to placed inside the set type. But the images are proleptically confusing, and must be analysed analeptically (after reading the instalment thoroughly) in order to make sense of them. The logic of presentation thus overrides the logic of textual authority.

Related Material

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- George Du Maurier, "Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?" — p. 94.

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- 1910 Frontispiece: "He felt himself suddenly seized round the neck." Page 279.

- The 1944 Illustrations by William Sharp for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone

- Gallery of Headnote Vignettes by William Jewett for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone in Harper's Weekly (4 January — 8 August 1868)

- Bibliography for both Primary and Secondary Sources for The Moonstone and British India (1868-2016)

Bibliography

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. With sixty-six illustrations by William Jewett. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Vol. 12 (1868), 4 January through 8 August 1868, pp. 5-529.

________. The Moonstone: A Romance. All the Year Round. 1 January-8 August 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Novel. With many illustrations. First edition. New York & London: Harper and Brothers, [July] 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Novel. With 19 illustrations. Second edition. New York & London: Harper and Brothers, 1874.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by George Du Maurier and F. A. Fraser. London: Chatto and Windus, 1890.

_________. The Moonstone, Parts One and Two. The Works of Wilkie Collins, vols. 5 and 6. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1900.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. With four illustrations by John Sloan. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1908.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by A. S. Pearse. London & Glasgow: Collins, 1910, rpt. 1930.

_________. The Moonstone. Illustrated by William Sharp. New York: Doubleday, 1946.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. With nine illustrations by Edwin La Dell. London: Folio Society, 1951.

Gregory, E. R. "Murder in Fact." The New Republic. 22 July 1878, pp. 33-34.

Karl, Frederick R. "Introduction." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Scarborough, Ontario: Signet, 1984. Pp. 1-21.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review Volume 42, Number 3 (Fall 2009): pp. 207-243. Accessed 1 July 2016. http://englishnovel2.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/files/2014/01/42.3.leighton-moonstone-serializatation.pdf

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, & Victorian Authorship. London and Ithaca, NY: Cornll U. P., 2001.

Peters, Catherine. The King of the Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. London: Minerva, 1991.

Reed, John R. "English Imperialism and the Unacknowledged crime of The Moonstone. Clio 2, 3 (June, 1973): 281-290.

Stewart, J. I. M. "A Note on Sources." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 527-8.

Vann, J. Don. "The Moonstone in All the Year Round, 4 January-8 1868." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 48-50.

Winter, William. "Wilkie Collins." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 203-219.

Created 26 November 2016

Last modified 1 November 2025