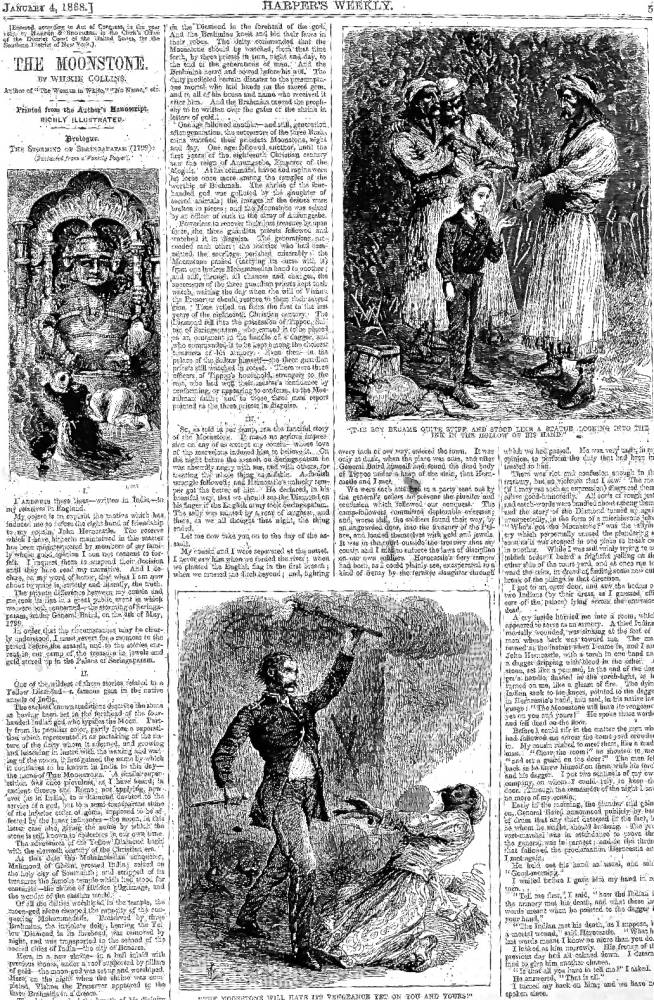

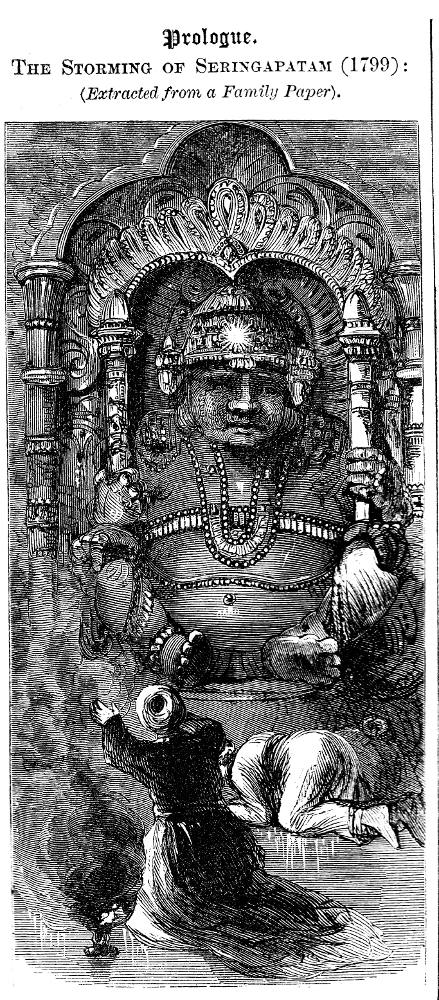

Uncaptioned headnote vignette for "The Storming of Seringapatam" (1799) — illustration for the first Harper's Weekly serial instalment of The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins (4 January 1868): 11.3 cm high by 5.5 cm wide (5 ⅝ by 2 ¾ inches). "Extracted from a Family Paper" — "Prologue III" in "First Period. The Loss of the Diamond (1848)." Page 5 (p. 9 in volume). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

The illustrations appearing here are courtesy of the E. J. Pratt Fine Arts Library, University of Toronto, and the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia.

Passage Introduced by the Dramatic Temple Scene at Benares

The volume edition's rendering of the same wood-engraving, left, p. 9.

[Having stormed the Moslem citadel, Colonel Herncastle and his cousin, the narrator here, are separated. When the narrator rejoins Herncastle, he discovers two Indians dead, and a third dying, all apparently murdered by the Colonel as they attempted to defend the idol of the Hindu Moon god from theft.]

(Extracted from a Family Paper)

[I]

I address these lines — written in India — to my relatives in England.

My object is to explain the motive which has induced me to refuse the right hand of friendship to my cousin, John Herncastle. The reserve which I have hitherto maintained in this matter has been misinterpreted by members of my family whose good opinion I cannot consent to forfeit. I request them to suspend their decision until they have read my narrative. And I declare, on my word of honour, that what I am now about to write is, strictly and literally, the truth.

The private difference between my cousin and me took its rise in a great public event in which we were both concerned — the storming of Seringapatam, under General Baird, on the 4th of May, 1799.

In order that the circumstances may be clearly understood, I must revert for a moment to the period before the assault, and to the stories current in our camp of the treasure in jewels and gold stored up in the Palace of Seringapatam.

[II]

One of the wildest of these stories related to a Yellow Diamond — a famous gem in the native annals of India.

The earliest known traditions describe the stone as having been set in the forehead of the four-handed Indian god who typifies the Moon. Partly from its peculiar colour, partly from a superstition which represented it as feeling the influence of the deity whom it adorned, and growing and lessening in lustre with the waxing and waning of the moon, it first gained the name by which it continues to be known in India to this day — the name of THE MOONSTONE. A similar superstition was once prevalent, as I have heard, in ancient Greece and Rome; not applying, however (as in India), to a diamond devoted to the service of a god, but to a semi-transparent stone of the inferior order of gems, supposed to be affected by the lunar influences — the moon, in this latter case also, giving the name by which the stone is still known to collectors in our own time.

The adventures of the Yellow Diamond begin with the eleventh century of the Christian era. — "The Prologue, The Storming of Seringapatam (1799)," Sections I-II, p. 5 (p. 9 in volume)

Commentary for Three Illustrations in the First Instalment: 4 January 1868

The initial headnote vignette for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance in Harper's Weekly (4 January 1868), page 5, bears no caption, so that the reader must construe its meaning from the opening paragraphs. The function of the headnote vignettes here, as in the Harper's Weekly printings of Charles Dickens's weekly serials A Tale of Two Cities in 1859 and Great Expectations in 1860-1861, seems to have been proleptic, focussing the reader's attention on the chief character, setting, or action of the weekly instalment. The small-scale image, just 11.3 by 5.5 cm, shows the interior of the Hindu Temple of the Moon at Benares before the initial theft of the diamond, which passes from the sacred edifice into a Moghul armoury and thence into a English bank (from the sacred to the profane, so to speak).

The first three illustrations together create a sweeping visual mini-narrative of the diamond's trajectory from the Indian shrine at Benares to the siege of Seringapatam to the Indians' quest to recover their stolen religious object in Britain. The linked images span from the eleventh century to the Victorian present and from ancient India to modern England, anticipating the enormous time scale as well as the cultural and geographical scope of Collins's narrative. [Leighton and Surridge, 211]

In the initial illustration, a mere vignette, the Moon god dominates the composition, dwarfing the incense-burner and two prostrate brahmins. The Buddha-like statue with the diamond in its forehead grips two stone torches which frame the larger-than-life figure and suggest an architectural setting; in other words, the two prostrate priests, the incense burner, and the seated deity all imply a Benares temple, a sacred space in India's most sacred city. The twin torches held by the deity are repeated in Colonel John Herncaste's torch and dagger, symbols of destruction rather than spiritual enlightenment. In the second and third illustrations, the spaces described offer contrasts, for the second is a constructed space, the armoury of a Moslem potentate who has relegated the sacred diamond to the status of mere ornament (in the handle of a dagger, which the uniformed Englishman holds as a symbol of imperial force of arms) and a natural scene on the estate of an aristocratic English family.

Moreover, the American illustrations efface any ideological distance between the reader and the imperial narrative, placing the viewer on the very edge of the murder scene at the siege, witnessing Herncastle with the dripping dagger in his hand. The dying Indian guard falls away from the diamond (now in the dagger’s pommel), a composition that reverses the reverential pose depicted in the chapter head, and strongly suggests that the murder constitutes religious or cultural violation as well as personal assault. Part 1's page layout, which links the Moon God, the crime of murder, and the Indians' start of their search in England, thus suggests a strongly sympathetic attitude to the Indians' quest for the diamond, arguably more so than in the unillustrated novel. In addition, the first page of the Harper's serial introduces more visual perspectives than the letterpress, further complicating the points of view from which we see the cultural expropriation of the diamond. Part 1's letterpress begins with John Herncastle's cousin narrating the siege of Seringapatam (1799) and then shifts to the perspective of Gabriel Betteredge on recent domestic British events (1848). However, the Harper's illustrators provide two additional points of view. First, the image of the Benares shrine lies outside the text's predominantly British perspective, giving us a view that Herncastle's cousin refers to as existing only in "stories" and "traditions" and that situates the American reader at the foot of the Indian shrine at a time before the British presence on the continent. Moving to the right of the page, we get a radically proleptic view of Franklin Blake’s glimpse (narrated to Betteredge in Part 3) of the Indians mesmerizing the English boy in their quest to recover the missing diamond. Finally, in the third illustration, we share the cousin's shocking view of John Herncastle murdering the Indian guard in order to steal the moonstone. Notably, this the only image that shares the narrative perspective of Part 1's letterpress as well as the only illustration accompanied by matching letterpress in the instalment: “The dying Indian sank to his knees, pointed to the dagger in Herncastle's hand, and said, in his native language: 'The Moonstone will have its vengeance yet on you and yours!'" (4 Jan. 1868, p. 5). This illustration, then, sutures the reader into the narrative at the very point at which Free considers that the letterpress creates ideological distance between the reader and the witnessing of imperial crime. [Leighton and Surridge, p. 213]

Taken as an interconnected trio, the three illustrations summarize the sweeping action of the first instalment, introducing the diamond's sacred nature, bringing on stage the European thief and murderer whose actions are apparently state-sanctioned, and concluding in the recent past (twenty years before the story's publication) with the descendants of the priests in the two previous frames who, as the present-day "guardians" of the gem, must locate and recover it, perhaps aided by supra-rational means (the clairvoyant). Like F. A. Fraser in the 1890 illustration 'The Indian — first touching the boy's head and making signs over it in the air — then said, 'Look!' for the Chatto and Windus edition, the American serial illustrator regards the three disguised Indians as serious of purpose and not mere charlatans and thieves as Betteredge construes them. For the relationship between the initial vignette and the other two illustrations on page 5, see https://archive.org/stream/harpersweeklyv12bonn#page/4/mode/2up.

In addition, the first page of the Harper's serial introduces more visual perspectives than the letterpress, further complicating the points of view from which we see the cultural expropriation of the diamond. Part 1's letterpress begins with John Herncastle's cousin narrating the siege of Seringapatam (1799) and then shifts to the perspective of Gabriel Betteredge on recent domestic British events (1848). However, the Harper's illustrators provide two additional points of view. First, the image of the Benares shrine lies outside the text's predominantly British perspective, giving us a view that Herncastle's cousin refers to as existing only in "stories" and "traditions” and that situates the American reader at the foot of the Indian shrine at a time before the British presence on the continent. Moving to the right of the page, we get a radically proleptic view of Franklin Blake's glimpse (narrated to Betteredge in Part 3) of the Indians mesmerizing the English boy in their quest to recover the missing diamond. [Leighton and Surridge, 213]

Relevant Plates from Volume Edition: 1868, 1874 (Harper's) and 1900 (Collier's)

- The Idol of the Moon God (Peter Fenelon Collier)

- The Diamond and the Ganges (Harper & Bros.)

Related Material

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- George Du Maurier, "Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?" — p. 94.

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- The 1944 Illustrations by William Sharp for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone (1946)

- 1910 Frontispiece: He felt himself suddenly seized round the neck. Page 279.

- Bibliography for both Primary and Secondary Sources for The Moonstone and British India (1868-2016)

- Gallery of Headnote Vignettes by William Jewett for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone in Harper's Weekly (4 January — 8 August 1868)

Bibliography

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. With sixty-six illustrations by William Jewett. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Vol. 12 (1868), 4 January through 8 August 1868, pp. 5-529.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. All the Year Round. 1 January-8 August 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. With 66 illustrations. Vol. 12 (1 January-8 August 1868), pp. 5-503.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by William Jewett. New York: Harper & Bros., 1871.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by George Du Maurier and F. A. Fraser. London: Chatto and Windus, 1890.

_________. The Moonstone, Parts One and Two. The Works of Wilkie Collins, vols. 5 and 6. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1900.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by A. S. Pearse. London & Glasgow: Collins, 1910, rpt. 1930.

_________. The Moonstone/span>. Illustrated by William Sharp. New York: Doubleday, 1946.

Stewart, J. I. M. "Introduction" to Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone." Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1966. Pp. 7-24.

Stewart, J. I. M. "A Note on Sources." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 527-8.

Vann, J. Don. "The Moonstone in All the Year Round, 4 January-8 1868." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 48-50.

Winter, William. "Wilkie Collins." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 203-219.

Created 22 November 2016

Last updated 26 October 2025