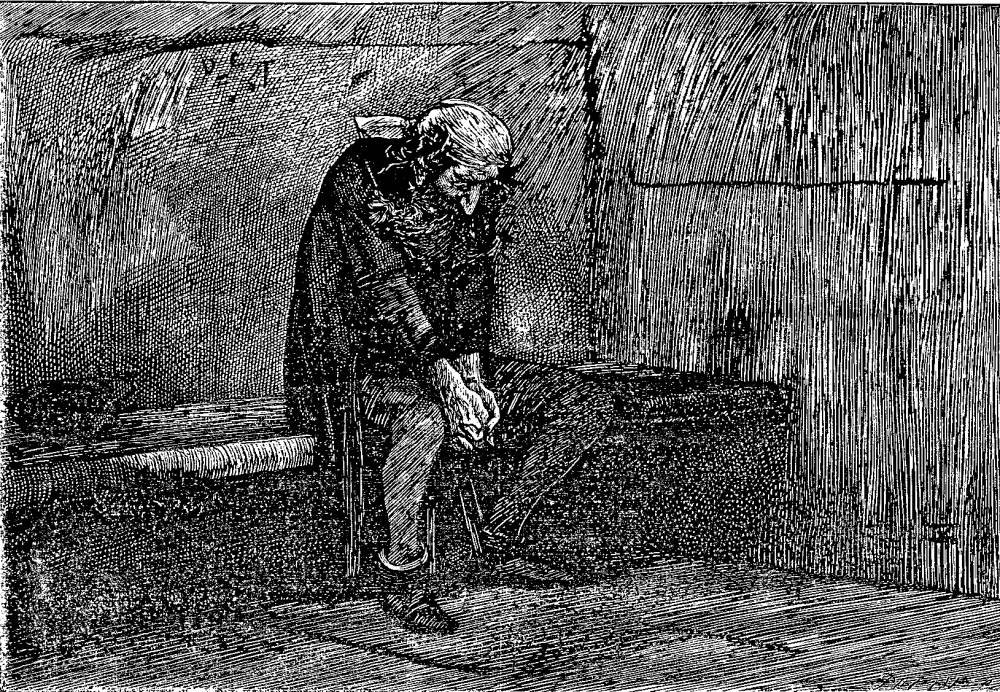

The Shade of Agnes

Harry Furniss

1910

14.0 x 9.5 cm vignetted

Final illustration for The Adventures of Oliver Twist in Oliver Twist and A Child's History of England, Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910), vol. 3, facing 416.

See commentary below

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

Within the altar of the old village church there stands a white marble tablet, which bears as yet but one word:, — "AGNES." There is no coffin in that tomb; and may it be many, many years, before another name is placed above it! But, if the spirits of the Dead ever come back to earth, to visit spots hallowed by the love — the love beyond the grave — of those whom they knew in life, I believe that the shade of Agnes sometimes hovers round that solemn nook. I believe it none the less because that nook is a Church, and she was weak and erring. [Thus closes the novel.]

[Chapter 53, "And Last," 418]

Commentary

Although Dickens's official illustrator for Oliver Twist in the 1837-8 serial, George Cruikshank, felt that the so-called Fireside illustration adequately summed up Providence's rewarding Oliver for his courage and upright character in the face of adversity and moral degradation, Dickens found it trite and conventional — and having access to the official biography by Dickens's lifelong friend and business agent, Harry Furniss would have known about this issue. John Forster, Dickens's official biographer (and therefore admittedly hardly an unbiased commentator) recounts the story of the so-called "cancelled plate" in such a manner that Dickens's high-handedness with veteran illustrator George Cruikshank is mitigated:

when Bentley decided to publish Oliver in book form before its completion in his periodical, Cruikshank had to complete the last few plates in haste. Dickens did not review them until the eve of publication and objected to the Fireside plate ("Rose Maylie and Oliver" [the final plate in vol. III]). Dickens had Cruikshank design a new plate [the Church plate] which retained the same title. This Church plate was not completed in time for incorporation into the early copies of the book, but it replaced the Fireside plate in later copies. Dickens not only objected to the Fireside plate, but also disliked having "Boz" on the title page. He voiced these objections prior to publication and the plate and title page were changed between November 9 [publication date] and 16." The publication had been announced for October, but the third-volume-illustrations intercepted it a little. . . . The matter supplied in advance of the monthly portions in the magazine, formed the bulk of the last volume as published in the book; and for this the plates had to be prepared by Cruikshank also in advance of the magazine, to furnish them in time for the separate publication: Sikes and his dog, Fagin in the cell, and Rose Maylie and Oliver, being the three last. None of these Dickens had seen until he saw them in the book on the eve of its publication; when he so strongly objected to one of them that it had to be cancelled. "I returned suddenly to town yesterday afternoon," he wrote to the artist at the end of October, "to look at the latter pages of Oliver Twist before it was delivered to the booksellers, when I saw the majority of the plates in the last volume for the first time. With reference to the last one — Rose Maylie and Oliver — without entering into the question of great haste, or any other cause, which may have led to its being what it is, I am quite sure there can be little difference of opinion between us with respect to the result. May I ask you whether you will object to designing this plate afresh, and doing so at once, in order that as few impressions as possible of the present one may go forth? [Forster, 92-94]

Wisely, when Chapman and Hall approached Dickens with the notion of issuing the novel in ten monthly parts for 1846, Dickens — perhaps feeling a little guilty about having compelled the veteran illustrator to replace at short notice the "cancelled" plate — nominated Cruikshank rather than his usual illustrator Hablot Knight Browne to design the green wrapper to contain the serial instalments. Significantly, perhaps, in his eleven vignettes on the wrapper Cruikshank alludes to neither the "Fireside" nor the "Church" scene that replaced it. The virtue of the "Church" plate must be that, although it does not enshrine Victorian family values as the "Fireside" plate does, it brings the story full circle, and ends with a serene contemplation of Oliver's mother, victim of the workhouse and New Poor Law system, a pauper not given even a proper burial — hence, the memorial rather than a grave or headstone in the "Church" plate that replaced the "Fireside" scene. A thorough Dickensian, Harry Furniss was likely familiar with this background through having read Forster's biography.

Since the Victorian reader tended to require the closure of the traditional happy ending, complete with a marriage and an even-handed disposition of poetic justice to all major characters in a story, the so-called "Fireside" plate would seem to be preferable. After all, in summing up the fate of Agnes Dickens (perhaps moved to contemplate the death of Mary Hogarth, his beloved sister-in-law) would seem to be touching on theological doctrine and metaphysical issues that were held to be beyond the scope of a mere mass entertainer, although he does not, like Harry Furniss seventy years later, actually show or narrate The Shade of Agnes hovering about the tombless memorial in the country church. Probably according to Dickens's explicit instructions, although never a good hand at female beauty, Cruikshank nevertheless depicts an almost tearful but dignified Rose patting Oliver on the shoulder as both solemnly contemplate the death of the beloved family member who fell through the gaps of the social welfare safety-net. Later artists have delivered closure by emphasizing the fate of Fagin, but for Dickens that matter had to be relegated to the penultimate illustration, Fagin in the Condemned Cell, which served as a model for both James Mahoney (1871) and Harry Furniss (1910).

According to Ruth Richardson in "The Subterranean Topography of Oliver Twist," the composition of the final illustration was informed by Dickens's knowledge of the workhouse located several doors down from where he and his family lived at Norfolk Street in London, although he disguised the location of Oliver's workhouse by placing it well north of London. When John Dickens was transferred from the Navy Pay Office in Portsmouth back to London in January 1815, the family lodged just off Fitzroy Square, on what was then Norfolk Street. He would have made the passing acquaintance of workhouse boys such as Oliver. In 1829-30, when Dickens would have been old enough to investigate his surroundings with a critical eye and a social conscience, the family returned to the area, staying above a grocer's shop at Number 10 Norfolk Street (now No. 22 Cleveland Street), the address which Dickens gave for his reader's ticket to the British Museum in February of 1830).

As the author of Dickens and The Workhouse (Oxford U. , 2012) and Dickens and Angela Burdett Coutts (forthcoming) historian, writer, and broadcaster Richardson, a thorough Londoner, knows much about the burial practices of the Cleveland Street Workhouse; here, just nine doors away, lived young Charles Dickens from 1828-31 in a building now distinguished by a blue historical plaque. The names of the occupants of nearby Marleybone houses and businesses of that period influenced Dickens's naming of characters in the novel: Sowerberry, Sikes, and Maylie. Mr. Baxter's pawnshop, which lay between the Dickenses' home and the workhouse may have contributed to the plot surrounding Agnes's locket since Mrs. Bumble retrieves it from a nearby pawnbroker's. But, most significantly, Dickens likely knew that the remains of paupers who died in the workhouse were disposed of via a system of subterranean passages, rather than accorded proper Christian burial. Hence, in the final illustration for the November 1838 triple-decker published by Richard Bentley, young radical writer Charles Dickens underscores the plight of the poor and their disrespectful treatment in death as in life. This "revised" illustration is therefore a mute protest against society's regarding the poor as mere "surplus population" to be disposed of as so much inert matter.

In the Cruikshank illustration, then, Oliver, once again in a tailored suit, stands beside the other respectable orphan, his mother's sister, Rose, who was fortunate enough to be adopted by a kindly, upper-middle-class family, and even more fortunate to become the wife of that family's educated son. George Cruikshank to please Dickens shows aunt and nephew in solemn profile to accentuate the familial likeness — and to emphasize that in a sense they are Agnes's final resting place, both in terms of sentiment, memory, and genetics. In accordance with Dickens's Protestant notions about appropriate church ornamentation, the setting is devoid of paintings, crucifixes, and even other memorials to the dead; nothing is to break the reader's identification between the two living figures, so much alike in their facial features that they might be mother and son, and the name "Agnes" in the simple plaque with a peak, suggestive perhaps of a house's roof in the neoclassical manner of monuments and tombs. This, then, was the point of departure for Harry Furniss's ultimate illustration, in which the etherial spirit of Oliver's mother, wearing a nun-like head-dress and assuming a pensive posture, hovers before the plaque in the church. However, Furniss's version of the memorial is a far grander and spiritual affair, which an elegant newel-post (right) suggesting an ornate railing, and a ledge underneath the inscribed name, the whole contained within a niche surmounted by a rounded cornice, implying that one is pondering the portal to the afterlife. In the Cruikshank original, there is a stone bench beneath the memorial, but in Furniss's there is merely step so that the visitor cannot sit before it, but turned away from the chapel monument. The overall effect, too, of these illustrations is quite different as Cruikshank's is sentimental yet realistic, and understated, whereas Furniss's is romantic, sensuous, and fanciful, energetically sketched in rather than realistically drawn three-dimensionally.

Relevant Illustrations from the original Volume Edition (1838), Diamond Edition (1867), and Household Edition (1871)

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's "Noah and Charlotte". Centre: George Cruikshank's "Oliver and His Family [The Fireside Plate]". Right: Mahoney's Household Edition illustration (1871) "He sat down on a stone bench opposite the door". [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. , 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. , 1980. 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 3.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. The Waverley Edition. Illustrated by Charles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912.

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. 1, book 2, chapter 3.

Lynch, Tony. "Cleveland Street, London." Dickens's England: An A-Z Tour of the Real and Imagined Locations. London: Batsford, 2012. 65.

Richardson, Ruth. "The Subterranean Topography of Oliver Twist," Dickensian Landscapes: 19th Annual Dickens Society Symposium. Domain de Sagnes, Beziers, France: 10 July 2014.

Created 26 January 2015