Alfred's Farewell

Harry Furniss

1910

13.5 cm high x 9.2 cm wide, framed

Dickens's Christmas Books, Charles Dickens Library Edition, VIII, facing 256.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Harry Furniss —> Christmas Books —> Charles Dickens —> Next]

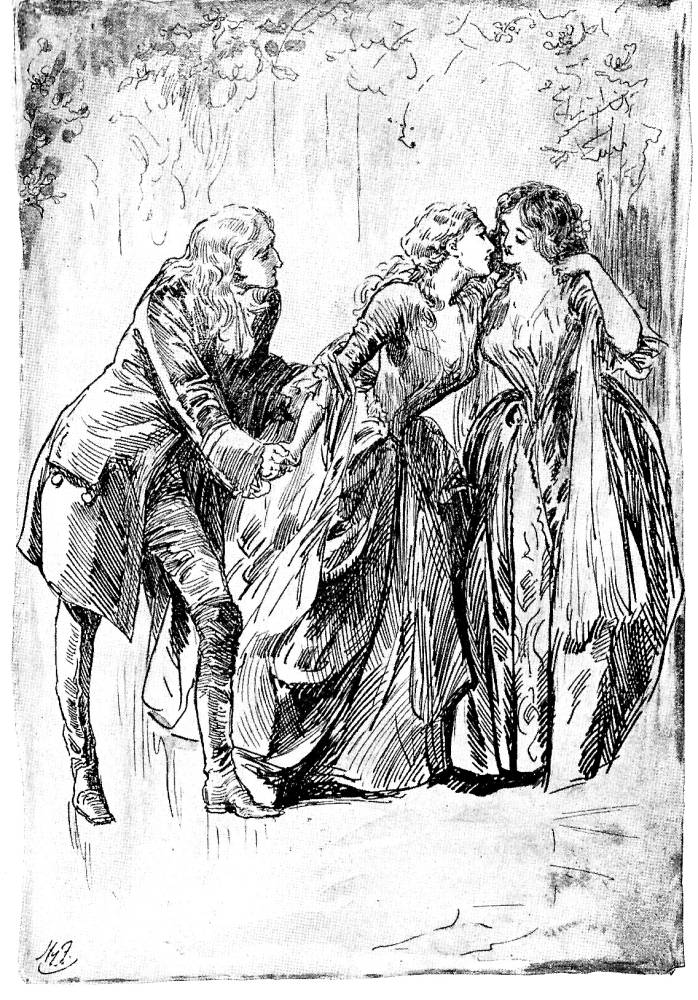

Alfred's Farewell

Harry Furniss

1910

13.5 cm high x 9.2 cm wide, framed

Dickens's Christmas Books, Charles Dickens Library Edition, VIII, facing 256.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Still the younger sister looked into her eyes, and turned not — even towards him. And still those honest eyes looked back, so calm, serene, and cheerful, on herself and on her lover.

"And when all that is past, and we are old, and living (as we must!) together — close together; talking often of old times," said Alfred — "these shall be our favourite times among them — this day most of all; and, telling each other what we thought and felt, and hoped and feared at parting; and how we couldn't bear to say good bye —"

"Coach coming through the wood!" cried Britain.

"Yes! I am ready — and how we met again, so happily, in spite of all; we'll make this day the happiest in all the year, and keep it as a treble birthday. Shall we, dear?"

"Yes!" interposed the elder sister, eagerly, and with a radiant smile. "Yes! Alfred, don't linger. There's no time. Say good bye to Marion. And Heaven be with you!" ["Part the First," 266: the original caption has received emphasis]

Whereas other illustrators have used images to set the late eighteenth-century, rural scene and introduce the cast of characters, Furniss has focussed on the key relationship of the "love story" — the romantic complication of both sisters' being in love with the same young man. Whereas the original illustrators and Fred Barnard in the Household Edition took care to establish the cast of characters and the eighteenth-century setting in the first movement of the love story — a story as much about the love of the Jeddler sisters Grace and Marion for one another as for Alfred Heathfield — later visual interpreter Harry Furniss, having at his disposal only five illustrations and certain of his readership's knowledge of the sixty-five-year-old novella, elected to focus at once on the romantic triangle: two young women both in love with the same eligible youth. In the process of delineating Alfred (left), Grace (centre, turned away from him), and Marion (right, focussing only on her sister), Furniss announces both the mainspring of the story's romantic plot and the chronological setting in that the figures are clearly wearing eighteenth-century costumes. These, however, are somewhat formal and costly in their manufacture, style, and materials for the children of a country doctor in a remote hamlet.

Although Furniss may not have been aware of E. A. Abbey's illustration "Meat?" said Britain, approaching Mr. Snitchey, with the carving knife and fork in his hands, and throwing the question at him like a missile for the Harper and Brothers American Household Edition, he would certainly have studied the original woodcuts dropped into the text of the single-volume first edition of 1846, and quite possibly Barnard's more realistic interpretations in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition of 1878, still selling well at the turn of the century and therefore familiar to a great many readers in the United Kingdom. In particular, Furniss seems to have borrowed notions of character from the original edition's initial illustration, Grace and Marion Jeddler Dancing, somewhat muting its exuberance, but nevertheless capturing the strong emotional bond between the sisters. The 1910 illustrator, however, dispenses entirely with such contextual material as the ghosts of the slain soldiers from the remote Civil War battle and the coming together of Dr. Jeddler and his family for a celebratory al fresco Parting Breakfast as his ward, Alfred Heathfield, leaves home for medical studies, a scene imitated by Sol Eytinge, Jr., in his Diamond Edition woodcut The Breakfast (1867).

For Furniss, the poses rather than the details carry the meaning. Even his orchard backdrop is realised impressionistically, with just the merest suggestion of boughs, leaves, and fruit; his focus is unswervingly on the three chief characters. These he defines in contradiction to Fred Barnard's study "Bye-the-bye," and he looked into the pretty face, still close to his, "I suppose it's your birthday" of the country philosopher and his two beautiful, teenaged daughters in period costume. In fact, in Furniss's sequence of five full-page illustrations Dr. Jeddler (characterised by Deborah A. Thomas as the story's central character) is nowhere to be found, despite the fact that his cynicism and parental status connect him with the protagonists of the previous Christmas Books, especially the benign Trotty Veck of The Chimes (1844).

As Jane Rabb Cohen notes, of all the Christmas Books, The Battle of Life "contains a minimum of merriment" (146). Although Dickens has made it something of a romantic comedy in that he emphasizes the elements of romance at the expense of character comedy (as afforded by Dr. Jeddler and his servants Benjamin Britain and Clemency Newcome), he was also thinking of his story in terms of the trials of Dr. Primrose and his family in Oliver Goldsmith's sentimental novella The Vicar of Wakefield (1766). The result is a work with less comic business than one would desire in a Christmas Book, so that, at least initially, Dickens has given the graphic humourist Harry Furniss little to work with. And, indeed, a kind of high moral seriousness informs all of Furniss's plates in this sequence, except the rather lacklustre comic scene of Clemency and Britain.

Left: Daniel Maclise's Frontispiece and John Leech's The Parting Breakfast; centre, Fred Barnard's "Bye-the-bye," and he looked into the pretty face, still close to his, "I suppose it's your birthday." (1878)

Above: Abbey's American Household Edition illustration "Meat?" said Britain, approaching Mr. Snitchey, with the carving knife and fork in his hands, and throwing the question at him like a missile. (1876).

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "John Leech." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio U. , 1980, 141-51.

Dickens, Charles. The Battle of Life. A Love Story. Illustrated by John Leech, Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846.

__________. The Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910, VIII, 79-157.

__________. The Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

__________. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Thomas, Deborah A. Chapter 4, "The Chord of the Christmas Season." Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982, 62-93.

Created 17 July 2013

Last modified 3 January 2020