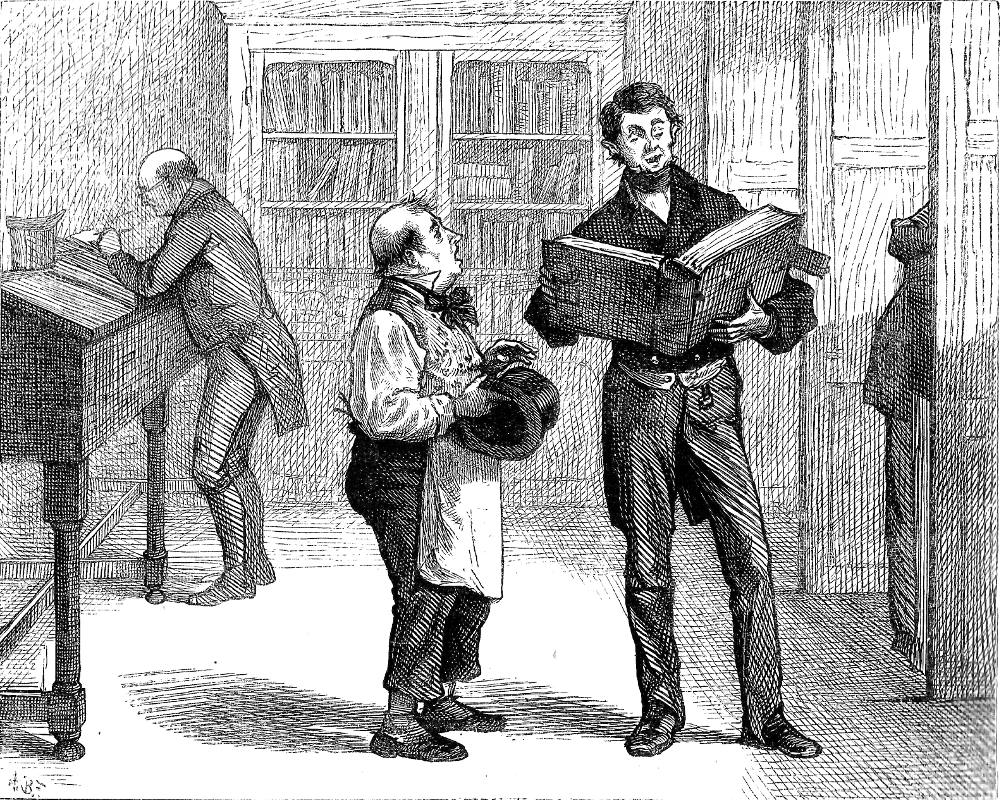

"It was quite apparent that it was a hopeless case." in Chapter VIII of "Scenes" — "Doctors' Commons," in Dickens's Sketches by Boz Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People (1877). Middle of page 122. Wood-engraving; 4 ¼ by 5 ¼ inches (10.2 cm high by 13.4 cm wide), framed. Since Frost was not familiar with the setting, has not delineated the backdrop with any degree of specificity, other than to show the long desk which Dickens describes. Instead, he focuses upon the little tradesman or porter making enquiries and the tall, lean clerk who, armed with expert knowledge, reads the document so rapidly and in such technical language that he utterly befuddles the amateur researcher.

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliographical Information

The 1876 and 1877 Household Editions of Dickens's Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People contain just a single wood-engraving for "Doctors' Commons," namely the present illustration, which appears on p. 122 in the 1877 Harper and Brothers edition with the following descriptive headline on the same page: "The Arches Court," the same headline for this article in the Chapman and Hall edition, page 41.

Passage Realised: In the Prerogative Office

The room into which we walked, was a long, busy-looking place, partitioned off, on either side, into a variety of little boxes, in which a few clerks were engaged in copying or examining deeds. Down the centre of the room were several desks nearly breast high, at each of which, three or four people were standing, poring over large volumes. As we knew that they were searching for wills, they attracted our attention at once.

It was curious to contrast the lazy indifference of the attorneys’ clerks who were making a search for some legal purpose, with the air of earnestness and interest which distinguished the strangers to the place, who were looking up the will of some deceased relative; the former pausing every now and then with an impatient yawn, or raising their heads to look at the people who passed up and down the room; the latter stooping over the book, and running down column after column of names in the deepest abstraction.

There was one little dirty-faced man in a blue apron, who after a whole morning’s search, extending some fifty years back, had just found the will to which he wished to refer, which one of the officials was reading to him in a low hurried voice from a thick vellum book with large clasps. It was perfectly evident that the more the clerk read, the less the man with the blue apron understood about the matter. When the volume was first brought down, he took off his hat, smoothed down his hair, smiled with great self-satisfaction, and looked up in the reader’s face with the air of a man who had made up his mind to recollect every word he heard. The first two or three lines were intelligible enough; but then the technicalities began, and the little man began to look rather dubious. Then came a whole string of complicated trusts, and he was regularly at sea. As the reader proceeded, a, and the little man, with his mouth open and his eyes fixed upon his face, looked on with an expression of bewilderment and perplexity irresistibly ludicrous. ["Scenes," Chapter VIII, "Doctors' Commons," pp. 122-123]

The Incident Realised: A Terribly Confused Client

The scene that Frost has realised does not take place in the Doctors' Commons at all, but nearby in the vicinity of St. Paul's Churchyard, in the "Prerogative Office," a repository for wills. Since Frost at this point in his life was not personally familiar with London scenes and locales, he has had to base the illustration solely on Dickens's description of the room where the clerks make wills available for those conducting personal and legal research. Although Dickens describes only the client, Frost has also provided the clerk with very specific features, making him by virtue of his visage, beard, and height look more than a little like Abraham Lincoln. No other illustrator of Sketches by Boz has realised the Prerogative Office, choosing instead in this section of the book such topics as the second-hand shops in "Monmouth Street" (Cruikshank), "The Gravesend Boat" (Barnard), and "The Last Cab-driver" (Eytinge). Charles Dickens made Doctors' Commons familiar to nineteenth-century readers through his protagonist's serving as a proctor there in David Copperfield (1849-50).

Other Realisations of Doctors' Commons (1850-67)

Above: The room as it looked some years after Dickens published his article: The Prerogative Court in The Illustrated London News, 1 June 1850: 399. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Above: The illustration which marks the end of the Doctors' Commons: Demolition of Doctors’ Commons in The Illustrated London News, 4 May 1867: 440. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Related Material

Bibliography

Barnard, J. "Fred" (il.). Charles Dickens's Sketches by Boz, with thirty-four illustrations. The Works of Charles Dickens: The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Volume 13.

Bentley, Nicholas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens: Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Dickens, Charles. "Scenes," Chapter 8, "Doctors' Commons." Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor & Fields edition]. Pp. 267-69.

Dickens, Charles. "Doctors' Commons." Pictures from Italy, Sketches by Boz and American Notes. Illustrated by Thomas Nast and Arthur B. Frost. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1877 (copyrighted in 1876).

Dickens, Charles. "Doctors' Commons." American Notes for General Circulation and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by J. Gordon Thomson and A. B. Frost. London: Chapman and Hall, 1880. Pp. 120-22.

Last modified 17 June 2019