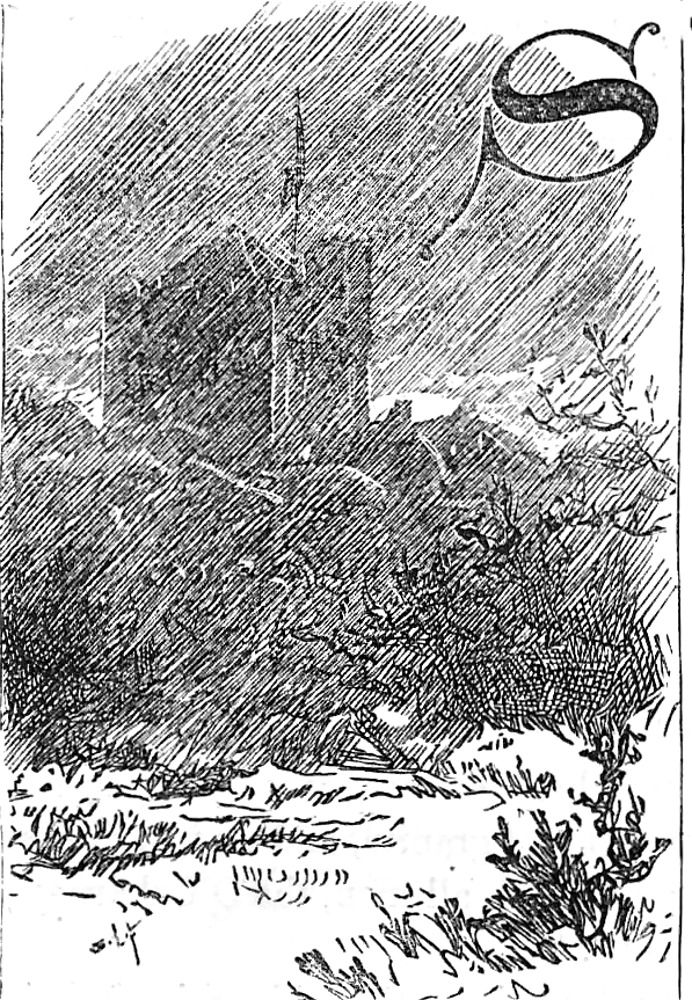

Initial letter S: a short, square tower, battlemented at top by Sir Luke Fildes; engraver, Swain. First initial-letter vignette for Charles Lever's Lord Kilgobbin, from the October 1870 number of the Cornhill Magazine, p. 493 in Vol. XXII. 7.4 cm by 5.0 cm (3 by 2 inches), framed. Part 1, Chapter I, "Kilgobbin Castle." The wood-engraver responsible for this thumbnail illustration was Joseph Swain (1820-1909), noted for his engravings of Sir John Tenniel's cartoons Punch. [Click on the image to enlarge it; mouse over links.]

Passage realised in Ch. 1, "Kilgobbin Castle Described"

On this border-land between fertility and destitution, and on a tract which had probably once been part of the Bog itself, there stood — there stands still — a short, square tower, battlemented at top, and surmounted with a pointed roof, which seems to grow out of a cluster of farm-buildings, so surrounded is its base by roofs of thatch and slates. Incongruous, vulgar, and ugly in every way, the old keep appears to look down on them — time-worn and battered as it is — as might a reduced gentleman regard the unworthy associates with which an altered fortune had linked him. This is all that remains of Kilgobbin Castle. [Cornhill, Vol. XXII, 494]

Right: The title-page for Volume XXII of the Cornhill Magazine (July-December, 1870).

Luke Fildes sets the keynote of the treachery and compromise that characterise Ireland's history from the Norman Conquest onwards with the image of the Norman keep of Kilgobbin Castle. His narrative of its history focuses not on its assassinated Anglo-Norman builder, Sir Hugh de Lacy, but on the Irish family who became its owners: the headstrong Kearneys, whose nineteenth-century representatives appear in many of the vignettes and full-page illustrations. The dark shading and gloomy sky above the mediaeval fortress set a sombre tone for the opening chapter. Indeed, Fildes' impressionism renders the squat, melancholy tower a character in its own right, and the artist piques the reader's curiosity: if the dilapidated castle is indeed a mere ruin, why is there a flag flying above it?

Fildes would have us regard the Norman keep not merely as a remnant of the past glories of the Kearneys, but symbolic of the current owner's fallen state. Through dissipation and gambling, fifty-something year-old Matthew Kearney has lost much of his estate, but he is still addressed by the villagers in the adjoining town of Moate as "My Lord," even though his peers merely address him as "Mr. Kearney." "By his son, Richard Kearney, he was always called ‘My lord’; while Kate [his daughter] as persistently addressed and spoke of him as papa" (494).

Commentary: The Fourteen Characters in the Initial-Letter Vignettes, Oct. 1870-March 1872

Although the format of the Cornhill Magazine may have compelled Fildes to base his vignette compositions on incidents that occurred on the opening pages of the eighteen instalments, he nonetheless often chose to make the reader search for the text realised on succeeding pages. His preference seems to be scenes with simple backdrops and just two characters: ten of the eighteen vignettes have only two characters each, with the first containing no character at all, just the turret of Kilgobbin Castle; instalments 5, 9, 11, 16, and 18 each show one character, and instalments 13 and 14 have three each. In terms of the number of times he realizes any given character, Fildes depicts Joe Atlee four times (numbers 2, 4, 7, and 15); Matthew Kearney, Lord Kilgobbin, four times (numbers 6, 10, 13, and 17); Dick Kearney three times (numbers 2, 4, and 8); Nina three times, including by herself (numbers 5 and 18), and with others in no. 12; Cecil Walpole three times (numbers 3, 7, and 12); Gorman O'Shea three times (numbers 10, 11, and 14); and Betty O'Shea twice (numbers 6 and 17). Two characters are anomalies, if we consider their relative importance in the story, for Lady Maude Bickerstaffe appears just once, in the vignette for the sixteenth instalment (January 1872), and Kate Kearney appears just once (in the vignette for the fourteenth instalment (November 1871). Miscellaneous appearances are made by such minor characters as an elderly carriage driver (no. 3); Mr. Justice Flood and Reverend Adams (no. 13); Dr. Rogan (no. 14); and the Turkish Grand Vizier (no. 15). Thus, although the eponymous character, Matthew Kearney, Lord Kilgobbin, appears in four of the eighteen vignettes, so does Trinity College student turned diplomat Joe Atlee. Moreover, the young women who constitute the novel's romantic interest appear far fewer than one might expect; even the exotic Nina appears in only three vignettes, and Kate Kearney and Lady Maud just once each.

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Lever, Charles. Lord Kilgobbin. The Cornhill Magazine. With 18 full-page illustrations and 18 initial-letter vignettes by S. Luke Fildes. Volumes XXII-XXV. October 1870-March 1872.

Lever, Charles. Lord Kilgobbin: A Tale of Ireland in Our Own Time. With 18 Illustrations by Sir Luke Fildes, R. A. London: Smith, Elder, 1872, 3 vols; rpt., Chapman and Hall, 1873.

Lever, Charles. Lord Kilgobbin. Illustrated by Sir Luke Fildes. Novels and Romances of Charles Lever. Vols. I-III. In three volumes. London: Smith, Elder, 1872, Rpt. London: Chapman & Hall, 1873. Project Gutenberg. Last Updated: 19 August 2010.

Stevenson, Lionel. Chapter XVI, "Exile on the Adriatic, 1867-1872." Dr. Quicksilver: The Life of Charles Lever. New York: Russell and Russell, 1939; rpt. 1969. Pp. 277-296.

Sutherland, John A. "Lord Kilgobbin." The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford U. P., 1989, rpt. 1990, 382.

University of Lincoln. "Review of Stephen Haddelsey's Charles Lever: The Lost Victorian (2000)." Abstract accessed 23 June 2023.

Created 7 June 2023 Updated 29 June 2023