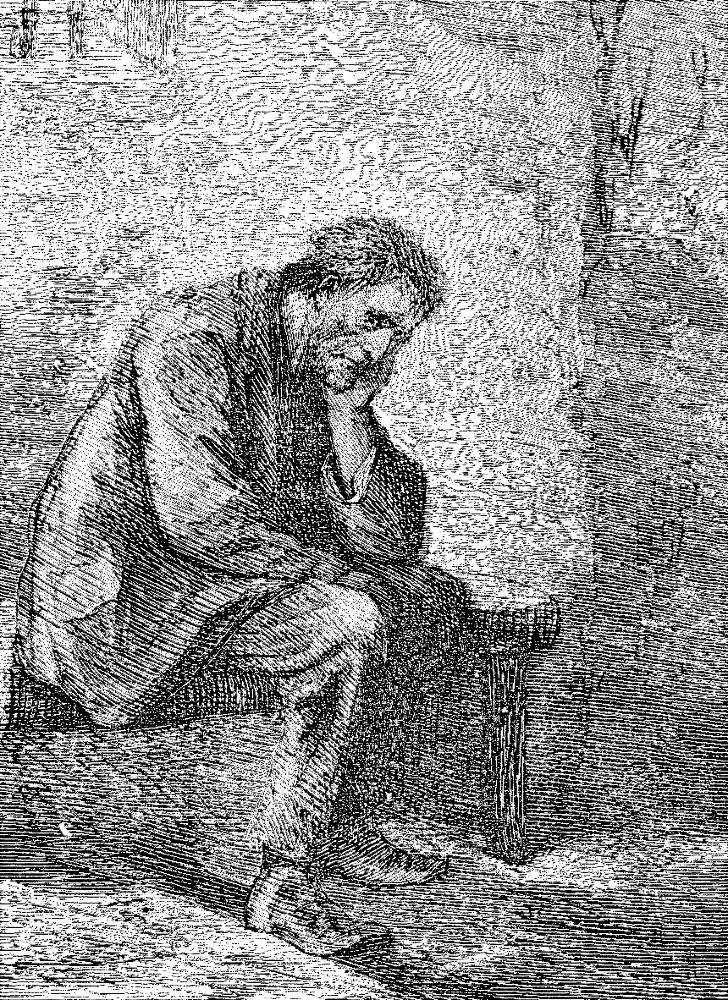

A Visit to Newgate

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Wood-engraving

10 x 7.5 cm (framed)

Dickens's Christmas Books & Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People (Diamond Edition), facing p. 336.

After the heart-warming, sentimental seasonal tales which Dickens wrote between 1843 and 1848, this volume of the Diamond Edition, commemorating Dickens's Second American Reading Tour, features seven scenes from Dickens's earliest work, "Our Parish," the twenty-five chapters from "Scenes," and twelve chapters from "Characters," the text established by Chapman and Hall in 1839.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

In the press-room below, were three men, the nature of whose offence rendered it necessary to separate them, even from their companions in guilt. It is a long, sombre room, with two windows sunk into the stone wall, and here the wretched men are pinioned on the morning of their execution, before moving towards the scaffold. The fate of one of these prisoners was uncertain; some mitigatory circumstances having come to light since his trial, which had been humanely represented in the proper quarter. The other two had nothing to expect from the mercy of the crown; their doom was sealed; no plea could be urged in extenuation of their crime, and they well knew that for them there was no hope in this world. "The two short ones," the turnkey whispered, "were dead men."

The man to whom we have alluded as entertaining some hopes of escape, was lounging, at the greatest distance he could place between himself and his companions, in the window nearest to the door. He was probably aware of our approach, and had assumed an air of courageous indifference; his face was purposely averted towards the window, and he stirred not an inch while we were present. The other two men were at the upper end of the room. One of them, who was imperfectly seen in the dim light, had his back towards us, and was stooping over the fire, with his right arm on the mantel-piece, and his head sunk upon it. The other was leaning on the sill of the farthest window. The light fell full upon him, and communicated to his pale, haggard face, and disordered hair, an appearance which, at that distance, was ghastly. His cheek rested upon his hand; and, with his face a little raised, and his eyes wildly staring before him, he seemed to be unconsciously intent on counting the chinks in the opposite wall. We passed this room again afterwards. The first man was pacing up and down the court with a firm military step — he had been a soldier in the foot-guards — and a cloth cap jauntily thrown on one side of his head.He bowed respectfully to our conductor, and the salute was returned. The other two still remained in the positions we have described, and were as motionless as statues. "Scenes," Chapter 25, "A Visit to Newgate," p. 342.

Commentary

In a Kafkaesque age, the scenes in Newgate Prison must have been terrifyingly relevant to twentieth-century readers, although the subject matter probably held little appeal for any but the most "reform-minded" Victorians. Neither Cruikshank (1839), nor Barnard (1876), nor Furniss (1910) have depicted any of the depressing scenes and unfortunate inmates in Dickens's "A Visit to Newgate," but the American illustrators Sol Eytinge, Junior, and Felix Octavius Carr Darley (despite their very limited programs of illustration) selected particularly telling moments from the sketch for visual realisation.

Charles Dickens's career as a writer of fiction began when, in 1833, aged just twenty-one, as a short-hand reporter turned political journalist he wrote a series of 'sketches' or observations on society, under the pen name of "Boz" (the nickname of his brother Augustus), for The Monthly Magazine. In 1835, the young publisher John Macrone suggested to Dickens that he publish his observations of London life and characters' stories in book form, offering him £100 for the copyright. As Dickens's annual income at the time was only £382, Dickens enthusiastically took up the challenge, rewriting a number of the previously published pieces, and adding five new ones especially for the 1836 two-volume set: "A Visit to Newgate," "The Black Veil," "The Great Winglebury Duel," "Our Next-Door Neighbour," and "The Drunkard's Death." The five "tales" possess something of the shape and structure of short stories rather than of mere sketches, reflecting Dickens's growing appreciation of plot and atmosphere. Settling with Macrone in late 1835 on the composition of the two-volume set, Dickens organized fifty-six pieces under four headings: "Our Parish" (seven), "Scenes" (twenty-five), "Characters" (twelve), and "Tales" (twelve) — and this was the format which Chapman and Hall retained in their 1839 single-volume edition, and which Ticknor and Fields borrowed intact for the thirteenth volume of the 1867 Diamond Edition.

In late October, before printing began, Dickens assured Macrone that he could easily supply 'two or three new Sketches', if necessary, to fill up the volumes, having memoranda by him for another nine or ten pieces. In the event,he had more than enough material and it was decidedto omit eight of the tales and sketches published before 1 November to make room for three new pieces, a hitherto unpublished comic tale called 'The Great Winglebury Duel', written for the Monthly, and two pieces especially for Macrone. The latter are of great interest as being the first things Dickens wrote for initial publication in permanent volume form, rather than a magazine or newspaper. Both are very 'dark'. The first, 'A Visit to Newgate', was written after Dickens and Macrone had been on a conducted tour of the prison (5 Nov.), undertaken by Dickens specifically to collect material. He took great pains with the writing and was highly gratified by the praise bestowed on it by [his father-in-law] Hogarth, Black, and others, including Macrone himself. Newgate had haunted his imagination since childhood, especially as the last home of those condemned at the Old Bailey to die upon the gallows. — Michael Slater, "'The Copperfield Days': 1828-1835," p. 56.

The shadow of the Marshalsea Debtors' Prison, where his father was incarcerated when Charles Dickens was just twelve (himself an economic prison, working long days at Warren's Blacking Factory, Hungerford Stairs), cast a long shadow through Dickens's life, provoking in him an exquisite sympathy for prisoners unjustly imprisoned — Samuel Pickwick, Charles Darnay, and Abel Magwitch are but a few of Dickens's virtuous men incarcerated by adverse circumstances and unfair statutes. In each case, as Slater remarks, "Dickens is clearly aimining at high seriousness" (56). The illustrations of "A Visit to Newgate" by Eytinge and Darley reflect this grave melancholy verging upon despair.

Dated by Bentley et al. to late November 1836 on account of the presence in the condemned cell of the robber Robert Swan and the unfortunate homosexuals John Smith and John Pratt (the latter two, unlike Swan, not reprieved, but executed on 27 November), "A Visit to Newgate" (the twenty-fifth and final "Scene") was one of three pieces in Sketches by Boz, volume one, in the first collection published by John Macrone that had not previously appeared in various London periodicals. Accordingly, as a fresh piece of writing produced immediately prior to volume publication, it was not accompanied by a Cruikshank illustration, and, in any event, though the master of caricature and the London scene, Cruikshank probably lacked the sympathy necessary for a telling visualisation of the suffering and distraught prisoners whom the dread sentence has stripped of all pretention, as in Eytinge's character study of despair personified. George Hogarth, an opera critic as well as an editor, praised the tale's "terrible power" in a review of the two-volume edition in the Chronicle for 11 February 1836, just three days after its publication: He pronounced it "even more pathetic and impressive" (cited in Slater, 62) than Victor Hugo's Dernier jour d'un condamné (1829).

As he describes the condemned cells, the most detailed portion of the essay, the narrator imagines himself a condemned felon during his last night on earth, dreaming of freedom and awakening to realize he has only two hours to live. — Paul Davis, 400.

Thus, Eytinge in his slection of subject for the essay "A Visit to Newgate" may have been influenced by Cruikshank's Fagin in the condemned Cell, The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Part 23, March 1839. Undoubtedly, Eytinge, working on his eight illustrations for Sketches by Boz two years after the publication of the elegantly illustrated pirated "Household Edition" frontispiece, had the opportunity to study the Visit to Newgate Darley engraving of 1864. However, whereas Darley's prison scene conveys elements of setting and suggests the relationship between his subjects as they converse in front of the floor-to-ceiling prison bars in the common area of Newgate, Eytinge focuses on the isolated prisoner's despondency. Darley describes the younger woman as sturdy, defiant, and suspicious as she glares in the direction of the viewer: "In one corner of this singular-looking den, was a yellow, haggard, decrepit old woman, in a tattered gown that had once been black, and the remains of an old straw bonnet, with faded ribbon of the same hue, in earnest conversation with a young girl — a prisoner, of course — of about two-and-twenty." Darley is interested in an inmate who is unbowed and stalwart, one who has yet to surrender to the hopelessness of Newgate. In contrast, Eytinge sets the keynote for the Dickens sketch, which begins on the page opposite, with this bent over, ill-kempt figure who has withdrawn into himself, apparently not even aware that he is being studied by the observant Boz. Above him is one of those grated windows that Dickens describes from the perspective of a pedestrian on the outside who scarcely bestows "a transient thought upon the condition of the unhappy beings immured in its dismal cells" (336), so that the illustration compels a binary perspective, as we see the outside and inside of Newgate simultaneously, moving from the thronging life of the street and "this gloomy depository of the guilt and misery of London" (336). Like a Rodin statue, the Eytinge's alienated and sequestered prisoner communicates through his form and posture a particular mental state which the artist wishes us, middle-class readers able to afford the luxury of a $1.50 volume, to appraise. This man, no matter what he has done, is hardly a depraved and vicious criminal — as Eytinge presents him, he is a fellow human being worthy of our interest and commiseration.

Compare to Eytinge's treatment in the Diamond Edition to that by his fellow American illustrator Felix Octavius Carr Darley, A Visit to Newgate, the frontispiece from Dickens's Sketches by Boz, Household Edition, vol. 1.

The Illustration from The 'Household Edition" (Sheldon & Co., New York), 1864

Above: Darley's beautifully engraved scene of two women in the depths of Newgate, A Visit to Newgate (1864) [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. "Scenes," Chapter 25, "A Visit to Newgate," Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 147-158.

Dickens, Charles. Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865. 2 vols.

Dickens, Charles. "Scenes," Chapter 25, "A Visit to Newgate." Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor & Fields edition]. Pp. 336-347.

Dickens, Charles. "Scenes," Chapter 25, "A Visit to Newgate," Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Pp. 94-101.

Dickens, Charles. "Scenes," Chapter 25, "A Visit to Newgate," Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 1. Pp. 189-203.

Dickens, Charles, and Fred Barnard. The Dickens Souvenir Book. London: Chapman & Hall, 1912.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Chapter 3, "Sketches by Boz." Dickens Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011. Pp. 12-15.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

Charles

Dickens

Sol

Eytinge

Next

Last modified 29 May 2017