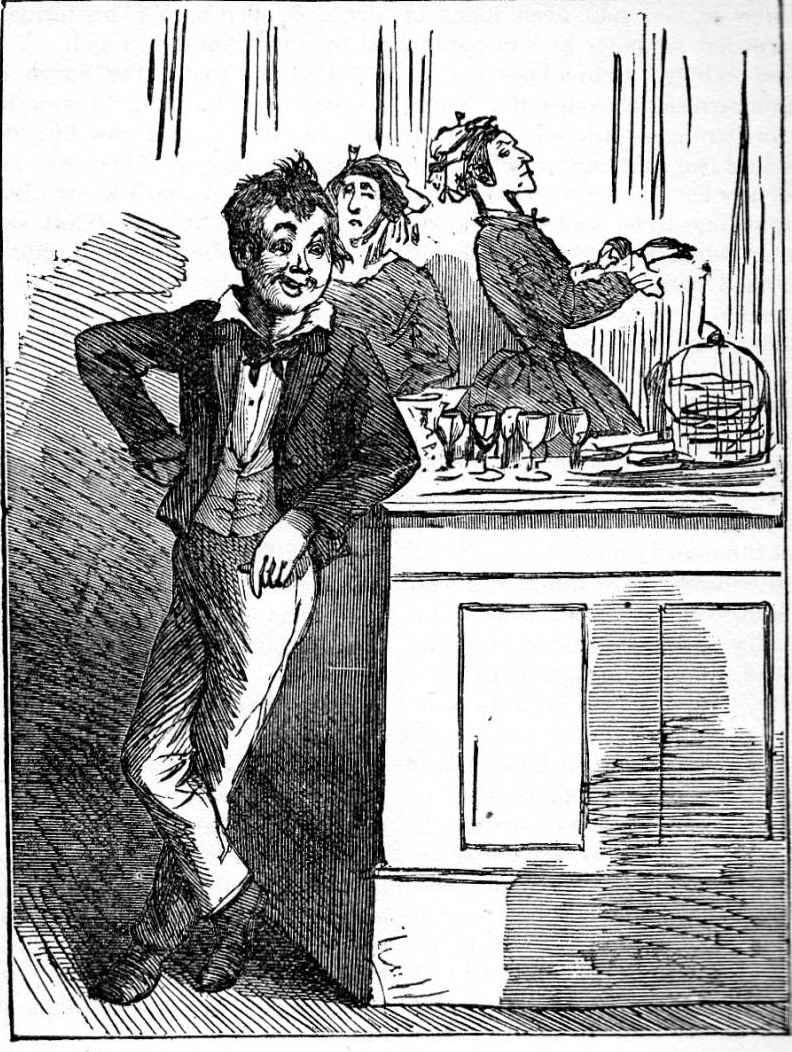

"The Boy at Mugby"

Sol Eytinge, Junior

1867

Wood-engraving

9.9 cm high x 7.4 cm wide

The sixth illustration for Dickens's Additional Christmas Stories in the Ticknor & Fields (Boston, 1867) Diamond Edition, facing page 302.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

Like "The Signal-Man" just preceding it, the satirical sketch re-titled "The Boy at Mugby" in the 1867 Diamond Edition volume, is not presented its original context as part of the framed-tale sequence entitled Mugby Junction, but as a detached, first-person narrative, with an impish refreshment-room boy serving as the street-wise commentator.

[Commentary continues below.]Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

I am the boy at Mugby. That's about what I am.

You don't know what I mean? What a pity! But I think you do. I think you must. Look here. I am the boy at what is called The Refreshment Room at Mugby Junction, and what's proudest boast is, that it never yet refreshed a mortal being.

Up in a corner of the Down Refreshment Room at Mugby Junction, in the height of twenty-seven cross draughts (I've often counted 'em while they brush the First-Class hair twenty-seven ways), behind the bottles, among the glasses, bounded on the nor'west by the beer, stood pretty far to the right of a metallic object that's at times the tea-urn and at times the soup-tureen, according to the nature of the last twang imparted to its contents which are the same groundwork, fended off from the traveller by a barrier of stale sponge-cakes erected atop of the counter, and lastly exposed sideways to the glare of Our Missis's eye — you ask a Boy so sitiwated, next time you stop in a hurry at Mugby, for anything to drink; you take particular notice that he'll try to seem not to hear you, that he'll appear in a absent manner to survey the Line through a transparent medium composed of your head and body, and that he won't serve you as long as you can possibly bear it. That's me.

What a lark it is! We are the Model Establishment, we are, at Mugby. Other Refreshment Rooms send their imperfect young ladies up to be finished off by our Missis. For some of the young ladies, when they're new to the business, come into it mild! Ah! Our Missis, she soon takes that out of 'em. Why, I originally come into the business meek myself. But Our Missis, she soon took that out of me.

What a delightful lark it is! I look upon us Refreshmenters as ockipying the only proudly independent footing on the Line. There's Papers, for instance, — my honourable friend, if he will allow me to call him so, — him as belongs to Smith's bookstall. Why, he no more dares to be up to our Refreshmenting games than he dares to jump a top of a locomotive with her steam at full pressure, and cut away upon her alone, driving himself, at limited-mail speed. Papers, he'd get his head punched at every compartment, first, second, and third, the whole length of a train, if he was to ventur to imitate my demeanour. It's the same with the porters, the same with the guards, the same with the ticket clerks, the same the whole way up to the secretary, traffic-manager, or very chairman. There ain't a one among 'em on the nobly independent footing we are. Did you ever catch one of them, when you wanted anything of him, making a system of surveying the Line through a transparent medium composed of your head and body? I should hope not. [p. 303]

Commentary

The Boy at Mugby thoroughly enjoys preying upon society, and he revels in his chosen occupation as 'a most highly delicious lark'. He depicts his exploits with such gusto, nevertheless, that it is impossible to deny him the kind of sympathy which Dickens himself must have felt when he signed a letter to his friend Thomas Beard 'The Boy (at Mugby)'. [Thomas, "Introduction to Charles Dickens: Selected Short Fiction, 25]

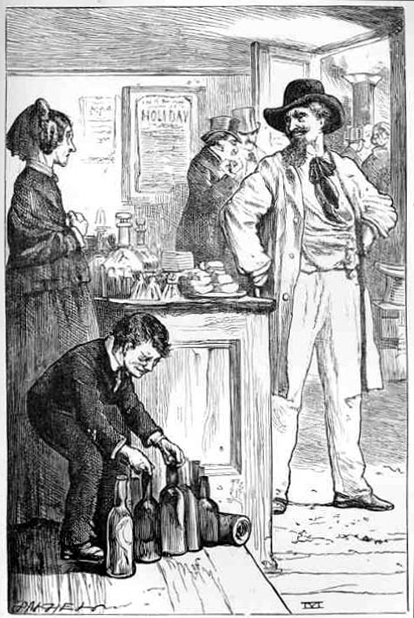

Sol Eytinge's relatively simple illustration nevertheless underscores the Boy's gleefully bragging about poor service and the unpalatable food and beverages inflicted upon the travelling public in Great Britain. In her introduction to the Penguin Classics collection of Dickens's short fiction, Deborah A. Thomas indicts the behaviour and attitude of the "irrepressible" food services functionary as tantamount to "juvenile delinquency" (25), but in his glee at cheating and insulting the travelling public he is merely reflecting the thinking and behaviour of his adult co-workers and superiors, so that readers still relish the cheeky Boy's derisive comments in spite of themselves. The figure of the Boy, a wizened adult picking up empty bottles, is not nearly so engaging in Mahoney's 1868 Illustrated Library edition illustration featuring the Gorgon of The Refreshment Room confronting an obstreperous American traveller about "self-service" in Mugby Junction.

In All the Year Round, 16 (7 December 1866), Mugby Junction included the following pieces: "Barbox Brothers" and "Barbox Brothers and Co." by Charles Dickens; "Main line. The Boy at Mugby" and "No. 1 branch line. The Signal-man" by Charles Dickens; "No. 2 Branch Line. The Engine-driver" by Andrew Halliday; "No. 3 Branch Line. The Compensation House" by Charles Allston Collins; "No. 4 Branch Line. The Travelling Post Office" by Hesba Stretton, and "No. 5 Branch Line. The Engineer" by Amelia B. Edwards. Here, then, late in the series of Christmas stories Dickens deviates from his established pattern in that he has not merely provided a framework that he and others fill, for he has written fully half of the Extra Christmas Number, and yet as the "Conductor" has offered no an anti-masque.

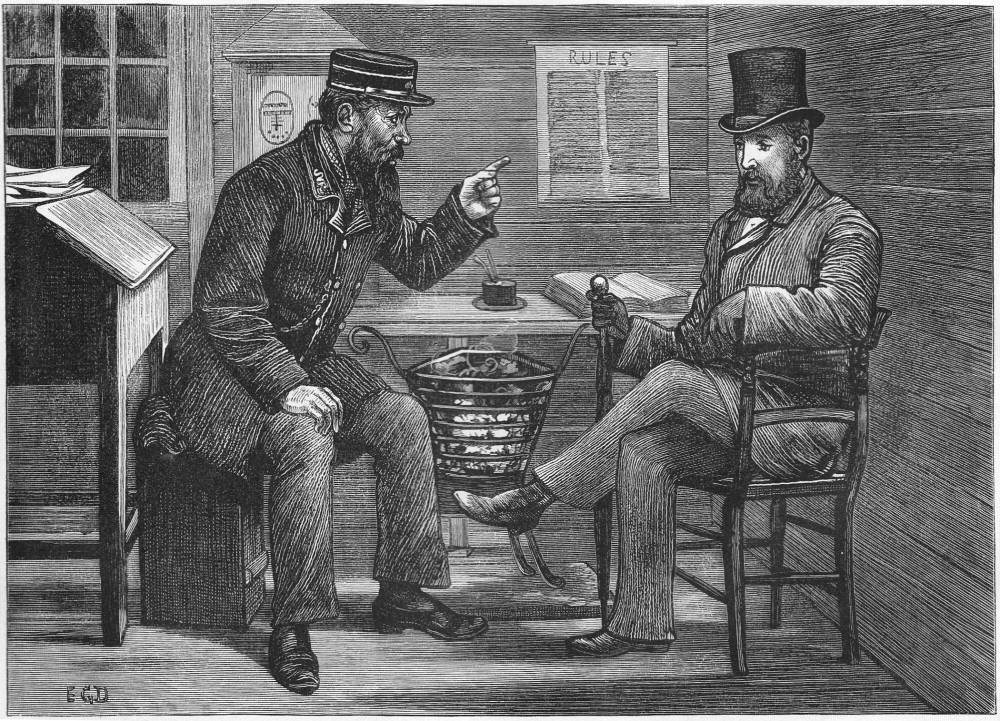

The Harry French illustrations for Mugby Junction in The Charles Dickens Library Edition, do not deal with either "The Boy at Mugby" or "The Signal-Man." Rather, The Face at the Window and Polly, Barbox Brothers' Guest at Dinner focus on the wanderings through Mugby of the Man from Nowhere in the first two stories. However, in the former illustration Furniss does capture something of the uncanny feeling that permeates the psychological ghost story, while in the latter he conveys the child's perspective on adult affairs that one finds in "The Boy at Mugby." Closest in spirit, then, to the playful humour of Eytinge is E. A. Abbey's I noticed that Sniff was agin a-rubbing his stomach with a soothing hand, and that he had drored up one leg, in which composition, however, Smiff and the Missis (the director of the food services operation) dominate, and the smirking Boy is relegated to the left-hand register at the back of the refreshment room. The theme of both American illustrations sounds a cautionary note to American tourists in Britain, where refreshment rooms (unlike those in France) will "Keep the public down." In contrast, Edward Dalziel's Household Edition illustration focuses on the relationship between Dickens's faneur, The Man from Nowhere, and the psychologically damaged Signal-man who is an extension of the vast railway machine.

Library, Household, and Charles Dickens Library Edition (1868, 1876-77, and 1910) Illustrations Relevant to "Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings" (1863)

Later Editions. Left: E. A. Abbey's "She prayed a good good prayer and I joined in it poor me." (1876). Right: E. G. Dalziel's "I took you for some one else yesterday evening. That troubles me" (1877). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Left: J. Mahoney's "Mugby Junction" (1868). Centre: Harry Furniss's "The Face at the Window and, right, "Polly, Barbox Brothers' Guest at Dinner (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books and The Uncommercial Traveller. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 10.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller and Additional Christmas Stories. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All The Year Round". Illustrated by Townley Green, Charles Green, Fred Walker, F. A. Fraser, Harry French, E. G. Dalziel, and J. Mahony. The Illustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1868, rpt. in the Centenary Edition of Chapman & Hall and Charles Scribner's Sons (1911). 2 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All the Year Round". Illustrated by E. G. Dalziel. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877.

Scenes and characters from the works of Charles Dickens; being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings, by Fred Barnard, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz); J. Mahoney; Charles Green; A. B. Frost; Gorgon Thomson; J. McL. Ralston; H. French; E. G. Dalziel; F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes; printed from the original woodblocks engraved for "The Household Edition.". New York: Chapman and Hall, 1908. Copy in the Robarts Library, University of Toronto.

Thomas, Deborah A. "Introduction." Charles Dickens: Selected Short Fiction. London: Penguin, 1976. Pp. 11-30.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

Christmas

Books

Sol

Eytinge

Next

Last modified 16 April 2014