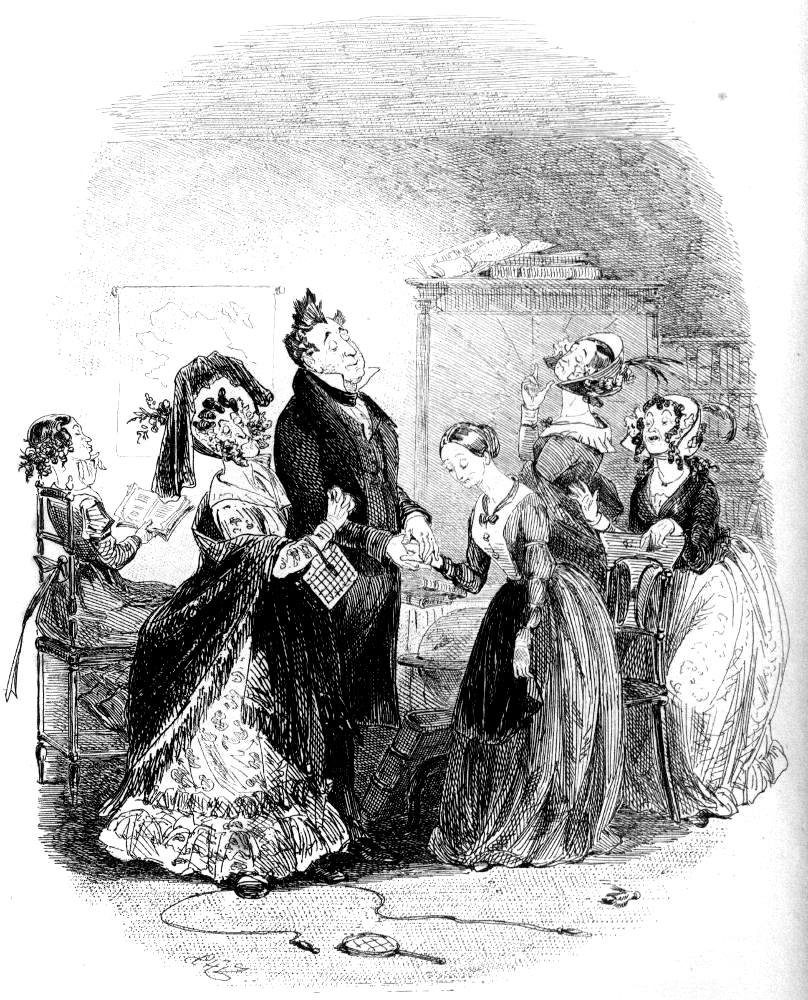

Mrs. Todgers and Mr. Moddle

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit (Diamond Edition)

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham; formatting by George P. Landow.

You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.

For his twelfth illustration of Martin Chuzzlewit, Eytinge depicted Mrs. Todgers, the owner of the London boarding-house where the Pecksniffs tend to stay when in town (e. g., in Part Four) and the youngest of her male lodgers, the disconsolate lover Augustus Moddle, who had fallen in love with Mercy ("Merry") Pecksniff and cannot completely permit her sister, Charity ("Cherry"), to displace the now Mrs. Chuzzlewit (Jonas's wife) in his affections. Introduced as early as chapter 9, Mr. Moddle, referred to only as "The youngest gentleman in company" (90) at that point, saves Pecksniff after the architect falls into the fireplace: Moddle "had him out in a second. Yes, before a hair upon his head was singed, he had him on the hearth-rug" (89-90). Ultimately, feeling trapped into a marriage wholly unsuited to his disposition, Moddle decamps to Van Dieman's Land (modern Tasmania). Mrs. Todgers, too, is involved in a romantic subplot, since she has cast her net upon the widower Seth Pecksniff. Dickens's description of her in chapter 8 presumably influenced Eytinge's conception of her, especially with respect to her curls, although not her taste for finery implied in Phiz's April 1843 illustration, for Part Four (chapter 9):

M. Todgers was a lady — rather a bony and hard-featured lady — with a row of curls in front of her head, shaped like little barrels of beer; and on the top of it something made of net, — you couldn't call it a cap exactly, — which looked like a black cobweb. She had a little basket on her arm, and in it a bunch of keys that jingled as she came. [Chapter 8; Diamond Edition, p. 74]

The kindly aspect of her disposition is not suggested in Eytinge's illustration, but her role as counsellor to the inmates of the boarding-house is well suggested by the illustration. The dialogue that Eytinge has in mind between Mrs. Todgers and Mr. Moddle occurs in the middle of the narrative, in chapter 32, when Charity has established herself at Mrs. Todgers's once again:

This was the only great change over and above the change which had fallen on the youngest gentleman. As for him, he more than corroborated the account of Mrs. Todgers; possessing greater sensibility than even she had given him credit for. He entertained some terrible notions of Destiny, among other matters, and talked much about people's 'Missions'; upon which he seemed to have some private information not generally attainable, as he knew it had been poor Merry's mission to crush him in the bud. He was very frail and tearful; for being aware that a shepherd's mission was to pipe to his flocks, and that a boatswain's mission was to pipe all hands, and that one man's mission was to be a paid piper, and another man's mission was to pay the piper, so he had got it into his head that his own peculiar mission was to pipe his eye. Which he did perpetually.

He often informed Mrs. Todgers that the sun had set upon him; that the billows had rolled over him; that the car of Juggernaut had crushed him, and also that the deadly Upas tree of Java had blighted him. His name was Moddle.

Towards this most unhappy Moddle, Miss Pecksniff conducted herself at first with distant haughtiness, being in no humour to be entertained with dirges in honour of her married sister. The poor young gentleman was additionally crushed by this, and remonstrated with Mrs. Todgers on the subject.

"Even she turns from me, Mrs. Todgers," said Moddle.

"Then why don't you try and be a little bit more cheerful, sir?" retorted Mrs Todgers.

"Cheerful, Mrs Todgers! cheerful!' cried the youngest gentleman; "when she reminds me of days for ever fled, Mrs. Todgers!"

"Then you had better avoid her for a short time, if she does,' said Mrs. Todgers, 'and come to know her again, by degrees. That's my advice."

"But I can't avoid her," replied Moddle, "I haven't strength of mind to do it. Oh, Mrs. Todgers, if you knew what a comfort her nose is to me!"

"Her nose, sir!" Mrs. Todgers cried.

"Her profile, in general," said the youngest gentleman, "but particularly her nose. It's so like," — here he yielded to a burst of grief, — "it's so like hers who is Another's, Mrs. Todgers!"

The observant matron did not fail to report this conversation to Charity, who laughed at the time, but treated Mr Moddle that very evening with increased consideration, and presented her side-face to him as much as possible. Mr. Moddle was not less sentimental than usual; was rather more so, if anything; but he sat and stared at her with glistening eyes, and seemed grateful.

"Well, sir!" said the lady of the boarding-house next day. 'You held up your head last night. You're coming round, I think."

"Only because she's so like her who is Another's, Mrs Todgers," rejoined the youth. "When she talks, and when she smiles, I think I'm looking on HER brow again, Mrs. Todgers." [Ch. 32, Diamond Edition, p. 294, facing the illustration]

Three illustrations of Todgers and Moddle. Left: Phiz's "Mrs. Todgers and the Pecksniffs Call Upon Miss Pinch" (April 1843). Centre: Phiz's "Mr. Moddle is Led to the Contemplation of his Destiny" (May 1844). Right: "Yes, sir" returned Miss Pecksniff, modestly. "I am — my dress is rather — really, Mrs. Todgers!" (Fred Barnard, Chapter 54, the Household Edition).

Whereas Eytinge thought the proprietress of the commercial boarding-house worthy of visual comment, Barnard relegates her to a corner of a single illustration late in the narrative in the 1872 Household Edition. Phiz, on the other hand, seems to have been content to let the reader imagine his appearance and manner resulting from his suffering from "a blighted heart" until well into the story, when in the May 1844 number he shows a pallid youth in respectable, middle-class garb accompanying Charity on a shopping expedition to set them up in housekeeping. Certainly in his twelfth illustration Eytinge captures Moddle's depressive state.

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (1842-43). Il. Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. Engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Il. Fred Barnard. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978.

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

Martin

Chuzzlewit

Sol

Eytinge

Next

Last modified 13 May 2012