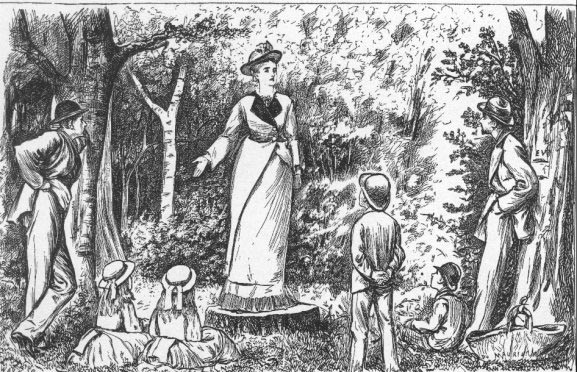

Round Her, Leaning Against Branches, or Prostrate on the Ground, Were Two or Three Individuals by George Du Maurier. The Cornhill Magazine, Vol. XXXII (September 1875), facing page 257 — third full-page illustration for Thomas Hardy's The Hand of Ethelberta, 10 cm high by 4.5 cm wide (3 ½ by 2 ½ inches), framed. Engraver Joseph Swain. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Passage Realised: Christopher Stumbles upon Ethelberta's Rehearsal

Thus slowly advancing, his ear caught, between the rustles, the tones of a voice in earnest declamation; and, pushing round in that direction, he beheld through some beech boughs an open space about ten yards in diameter, floored at the bottom with deep beds of curled old leaves, and cushions of furry moss. In the middle of this natural theatre was the stump of a tree that had been felled by a saw, and upon the flat stool thus formed stood Ethelberta, whom Christopher had not beheld since the ball at Wyndway House.

Round her, leaning against branches or prostrate on the ground, were five or six individuals. Two were young mechanics—one of them evidently a carpenter. Then there was a boy about thirteen, and two or three younger children. Ethelberta’s appearance answered as fully as ever to that of an English lady skilfully perfected in manner, carriage, look, and accent; and the incongruity of her present position among lives which had had many of Nature’s beauties stamped out of them, and few of the beauties of Art stamped in, brought him, as a second feeling, a pride in her that almost equalled his first sentiment of surprise. Christopher’s attention was meanwhile attracted from the constitution of the group to the words of the speaker in the centre of it—words to which her auditors were listening with still attention.

It appeared to Christopher that Ethelberta had lately been undergoing some very extraordinary experiences. What the beginning of them had been he could not in the least understand, but the portion she was describing came distinctly to his ears, and he wondered more and more. [Chapter XIII, "The Lodge (continued) — The Copse Behind"]

Commentary: Becoming a Professional Story-teller

The subject of the third plate, Ethelberta's rehearsing a sensational tale, is significant in that it foreshadows the success that she will have as a professional story-teller after Lady Petherwin's untimely demise. Ethelberta's attempting to assist her mother-in-law in rescuing the will from the flames at the very close of Chapter XI (X in the revised text) would have been as significant and much more dramatic — and certainly an illustration of Christopher's encountering Picotee at the portal of Arrowthorne Lodge would not merely have been more romantic, but would have served to establish the girl's infatuation with Christopher as an important strand in the novel's plot. When she indicates Mrs. Petherwin "is in the plantation with the children" (Ch. XII), we are alerted to the imminent arrival of the moment realized in the third plate. "The boughs were so tangled that he [Christopher] was obliged to screen his face with his hands," the scene in the initial-letter vignette, precedes his discovery of the natural amphitheater. Ethelberta's practice audience is "five or six individuals" — Sol and Dan (the "young mechanics"), Joey ("a boy about thirteen"), "and two or three younger children." The illustration contains two inaccuracies. First, du Maurier has made neither of Ethelberta's grown-up brothers look much like "a carpenter" (in fact, both are so respectably dressed that the reader would hardly think them "mechanics"). Du Maurier when working on this plate was probably not in possession of a proof of the following instalment, in which Hardy specifically identifies Ethelberta's nine siblings: Joey and Emmeline "of that transitional age" (12-14), "the two youngest children, Georgina and Myrtle," the absent grown-up sisters in domestic service (Gwendoline and Cornelia), the young workmen (Dan and Sol), and, of course, the pupil-teacher, Picotee. Du Maurier's third plate, then, is fundamentally incorrect, not merely in the fashionable costuming of the Chickerel family, but in their ages and numbers. If Dan and Sol are to the picture's extreme right and left, and if Georgina and Myrtle are on Ethelberta's left, the boy standing downstage must be Joey. Since Picotee is back at the cottage, attending her invalid mother, the last child, seated to the right, must be Emmeline, and not a boy. Hardy specifies in the next part that the family consists of "seven girls only" (p. 145).

Related Material

Scanned image and texts by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "The Only Artist to Illustrate Two of Thomas Hardy's Full-length Novels, The Hand of Ethelberta and A Laodicean: George du Maurier, Illustrator and Novelist." The Thomas Hardy Year Book, No. 40" Hardy's Artists. 2012. 54-128.

Hardy, Thomas. The Hand of Ethelberta: A Comedy in Chapters. The Cornhill Magazine. Vol. XXXII (1875).

Hardy, Thomas. The Hand of Ethelberta: A Comedy in Chapters. Intro. Robert Gittings. London: Macmillan, 1975.

Jackson, Arlene M. Illustration and the Novels of Thomas Hardy. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1981.

Page, Norman. "Thomas Hardy's Forgotten Illustrators." Bulletin of the New York Public Library 77, 4 (Summer, 1974): 454-463.

Sutherland, John. "The Cornhill Magazine." The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford U. P., 1989. 150.

Vann, J. Don. "Thomas Hardy (1840-1928. The Hand of Ethelberta in the Cornhill Magazine, July 1875-May 1876." in Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 83.

Created 16 January 2008

Last updated 17 January 2025