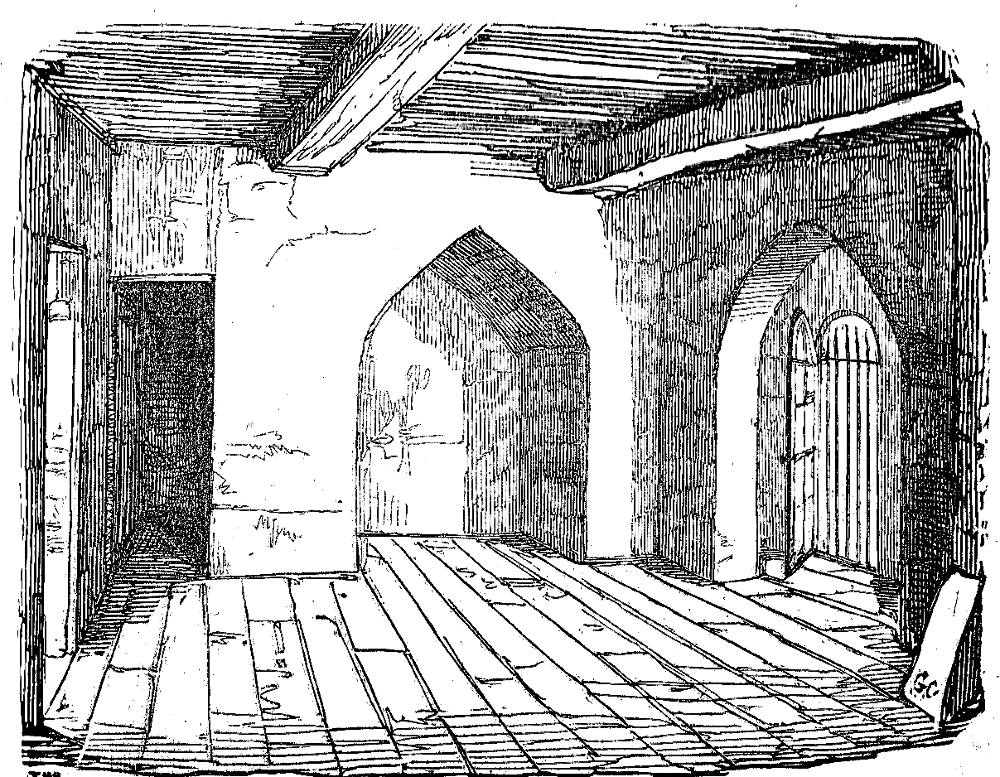

Upper Chamber in the Constable Tower. — George Cruikshank. Ninth instalment, September 1840 number. Sixty-fifth illustration and and thirty-sevenh wood-engraving in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. A Historical Romance. Illustration for Book the Second, Chapter XXIV. 7.7 cm high x 9.9 wide, vignetted, mid-p. 283: running head, "The Constable Tower." The prosaic line-drawing of the upper chamber does not contribute much to either the suspense of Xit's miraculous escape from Simon Renard and the torturers or the reader's appreciation of Xit's managing his escape, but it does depict yet another tower in the complex. Prior to the construction of the two-storey Tudor framed residence of the Lieutenant about 1530, the Constable of the Tower occupied the quarters which Cruikshank depicts in Chapters XXIII and XXIV. The Constable Tower, built during the reign of Henry III in the thirteenth century, served as the residence of the chief officer of the Tower of London until the more spacious and comfortable Tudor building replaced it. Finding his guards asleep in this upper chamber of the Constable Tower after his initial interrogation, Xit steals Nightgall's keys and effects his escape. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Associated Passage: Xit Escapes from the Constable Tower

He then began to consider whether it might not be possible to escape. With this view, he examined the embrazures, but they were grated, and defied his efforts to pass through. He next tried the door, and to his great surprise found it unfastened; having, most probably, been left open intentionally by Wolfytt. As may be supposed, Xit did not hesitate to avail himself of the chance thus unexpectedly offered him. Issuing forth, he hurried up a small spiral stone staircase, which brought him to the entrance of the upper chamber. The door was ajar, and peeping cautiously through it, he perceived Nightgall and Wolfytt, both asleep; the former reclining with his face on the table, which was covered with fragments of meat and bread, goblets, and a large pot of wine; and the latter, extended at full length, on the floor. It was evident, from their heavy breathing and disordered attire, they had been drinking deeply.

Stepping cautiously into the chamber, which in size and form exactly corresponded with that below, Xit approached the sleepers. A bunch of keys hung at Nightgall's girdle — the very bunch he had taken once before, — and the temptation to possess himself of them was irresistible. Creeping up to the jailor, and drawing the poignard suspended at his right side from out its sheath, he began to sever his girdle. While he was thus occupied, the keys slightly jingled, and Nightgall, half-awakened by the sound, put his hand to his belt. Finding all safe, as he imagined, he disposed himself to slumber again, while Xit who had darted under the table at the first alarm, as soon as he thought it prudent, recommenced his task, and the keys were once more in his possession. [Chapter XXIV. — "How Xit escaped from the Constable Tower; And How he found Cicely," pp. 282-83]

Commentary

The plucky dwarf, Xit, is not expecting the kind of interrogation tactics to which the authorities customarily subject suspects with information vital to the security of the regime. Consequently, having already spent a few minutes inside Scavenger's Daughter in the torture chamber, he takes the opportunity to escape when he discovers the drunken Nightgall and Wolfytt asleep in the upper chamber of the Constable Tower. Stealing Nightgall's complete set of keys to the Tower as well as his poignard, Xit discovers Nightgall's pass, "an order from the council to let the bearer pass at any hour whithersoever he would, through the fortress," which he immediately employs to get past sentinels on the roof and battlements. He then makes his way to the roof of the Broad Arrow Tower by way of the ballium wall.

Accordingly, he retraced the steps he had just mounted, and continued to descend till he reached an arched door. Unlocking it with one of the keys from his bunch, he entered a dark passage, along which he proceeded at a swift pace. His course was speedily checked by another door, but succeeding in unfastening it, he ran on as fast as his legs could carry him, till he tumbled headlong down a steep flight of steps. Picking himself up he proceeded more cautiously, and arrived, after some time, without further obstacle, at a lofty, and as he judged from the sound, vaulted chamber.

To his great dismay, though he searched carefully round it, he could find no exit from this chamber, and he was about to retrace his course, when he discovered a short ladder laid against the side of the wall. It immediately occurred to him that this might be used as a communication with some secret door, and rearing it against the wall, he mounted, and feeling about, to his great joy encountered a bolt.

Drawing it aside, a stone door slowly revolved on its hinges, and disclosed a small cell in which a female was seated before a table with a lamp burning upon it. She raised her head at the sound, and revealed the features of Cicely. [Close of Chapter XXIV. — pp. 285-86]

However, Ainsworth keeps readers in suspense for a number of chapters regarding the outcome of Xit's discovery of Cicely in the hidden dungeon of the Broad Arrow Tower, and their confrontation with the enraged Nightgall in the closing lines of the twenty-fourth chapter, towards the end of the ninth monthly instalment. Battle scenes and political machinations occupy Ainsworth's full attention until Chapter XXXV, in the final (December) instalment, when he finally reveals the fate of Nightgall and the secret of Cicely's birth.

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. 11 September 2017.

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 22 October 2017