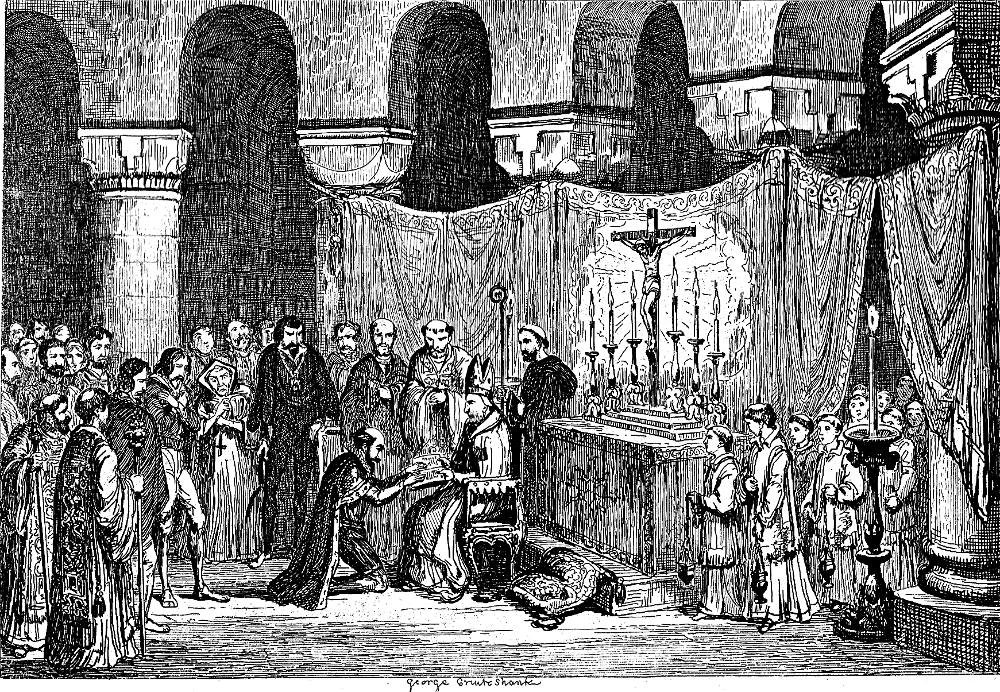

The Duke of Northumberland renouncing the Protestant Religion in St. John's Chapel — George Cruikshank. May 1840 number, fifth instalment. Thirty-third illustration in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. Steel-engraving 10.1 cm high x 14.7 wide, framed, facing p. 153. Having renounced his Protestant faith so publicly and with such fanfare in St. John's Chapelin the White Tower, Northumberland believes that he will be reprieved at the lastmoment on the scaffold. However, Simon Renard and Gunnora Braose have falselypromised him that Mary will spare his life simply so that the Duke will not have theopportunity to recant.Renard's plan seems to be succeeding brilliantly, sweeping away all significant actors who would oppose Catholic Mary's administration. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Complemented

Meanwhile, the whole nave of the church, the aisles, and the circular openings of the galleries above, were filled with spectators. A wide semicircle was formed around the converts. On the right stood several priests. On the left Simon Renard had planted himself, and near to him stood Gunnora; while, on the same side against one of the pillars, was reared the gigantic frame of Magog. A significant look passed between them as Northumberland knelt before the altar. Extending his arms over the convert, Gardiner now pronounced the following exhortation: — "Omnipotens sempiterne Deus hanc ovem tuam de faucibus lupi tua virtute subtractam paterna recipe, pietate et gregi tuo reforma piâ benignitate ne de familiâ tua damno inimicus exultet; sed de conversione et liberatione jus ecclesiam ut pia mater de filio reperto gratuletur per Christum Dominum nostrum."

"Amen!" ejaculated Northumberland.

After uttering another prayer, the bishop resumed his mitre, and seating himself upon the faldstool, which, in the interim, had been placed by the attendants in front of the altar, again interrogated the proselyte: — "Homo, abrcnuncias Sathanas et angelos ejus?"

"Abrenuncio," replied the Duke.

"Abrenuncias etiam omnes sectas hereticæ pravitatis?" continued the bishop.

"Abrenuncio,” responded the convert.

"Vis esse et vivere in imitate sancto fidei Catholico?" demanded Gardiner.

"Volo," answered the Duke.

Then again taking off his mitre, the bishop arose, and laying his right hand upon the head of the Duke, recited another prayer, concluding by signing him with the cross. This done, he resumed his mitre, and seated himself on the faldstool, while Northumberland, in a loud voice, again made a profession of his faith, and abjuration of his errors — admitting and embracing the apostolical ecclesiastical traditions, and all others — acknowledging all the observances of the Roman church — purgatory — the veneration of saints and relics — the power of indulgences — promising obedience to the Bishop of Rome, — and engaging to retain and confess the same faith entire and inviolated to the end of his life. "Ago talis," he said, in conclusion, "cognoscens veram Catholicam et Apostolicum fidem. Anathematizo hic publiée omnem heresem, procipuè illam de qua hactenus extiti." This he affirmed by placing both hands upon the book of the holy gospels, proffered him by the bishop, exclaiming, “Sic me Deus adjunct, et hoc sancta Dei evangelia!"

The ceremony was ended, and the proselyte arose. [Chapter VI. — By what means the Duke of Northumberland was reconciled to the Church of Rome," p. 152-53]

Commentary

Having renounced his Protestant faith so publicly in St. John's Chapel in the White Tower, Northumberland believes that he will be reprieved at the last moment on the scaffold. However, Simon Renard and Gunnora Braose have falsely promised that Mary will spare his life simply so that the Duke will not have the opportunity to recant. The viewer of the illustration before reading the accompanying text is likely to assess this as another of the ambitious Duke's stratagems, but in fact the illustration shows the success of Renard's plan to emasculate the leadership of the Protestant faction and asssure that none of her foremost enemies will survive to threaten the stability of Mary's reign — or his plan to unite the thrones of Spain and England through his master's marriage to Mary Tudor.

Cruikshank has just provided a far less dramatic view of Interior of Saint John's Chapel in the White Tower in the sixth chapter of Book Two, "By what means the Duke of Northumberland was reconciled to the Church of Rome." The prosaic wood-engraving records the same physical space that was the scene of Jane's gothic encounter with the mysterious, black-clad figure and the axe. A static architectural study of what the reader strolling through the White Tower in 1840 would have seen, the wood-engraving prepares the reader for the full-page engraving over the page in which the spiritual authorities effect the formal reinstatement of the devious and desperate Duke of Northumberland as a Catholic. He submits to an ecclesiastic authority before an altar loaded with candles and a large crucifix which imply the importance of the theatrical properties of Christianity to the Roman Catholic Church. The presence of so many courtiers and clergy as onlookers, the central position of recently elevated Bishop Gardiner in his mitre and vestments, and even the entrance of a choir of adolescent male singers in surplices signals the importance of the event both in the political and the religious life of the realm. Here in St. John's Chapel again history and romance intersect as the menace constituted by the anonymous, black-clad figure in Queen Jane's First Night in the Tower (Book the First, Chapter IV) in the fictional plot becomes the machiavellian Simon Renard, immediately behind Northumberland. The heretofore cunning Duke's strategy fails to convince Mary Tudor and her Council that the powerful magnate is no longer either a Protestant or a threat to national security. The strategy of having him renounce his Protestant convictions so publicly in fact has originated with Simon Renard, whose intention involves executing the devious Duke in spite of his perfidious promises to see that Mary spares Northumberland's life if he does not recant his re-conversion on the scaffold. Although Cruikshank's illustration does not reveal them, Northumberland is beginning to have misgivings.

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. 11 September 2017.

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 10 October 2017