The Prince, picking up Cinderella's Glass Slipper (6.9 cm high by 10.1 cm wide, facing page 19) — the sixth illustration for both the single-volume edition of 1854 and for the third tale in the 1865 anthology, George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. The enchanted pumpkin has done its work, depositing Cinderella at the ball; and her beauty and charm have captivated the Prince. But, as midnight approaches, Cinderella, bearing in mind the Dwarf's injunction, hastily departs, inadvertently leaving behind one of her glass dancing pumps, which the Prince now notices.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

The illustrations appearing here are from the collection of the commentator.

Passage Illustrated

At the banquet, she was placed on the left of the Queen, who treated her with the greatest kindness, as well as the King also. The Prince, of course, was unremitting in his attentions, and everything was done that was possible to make Cinderella happy and comfortable. She felt it ; when, suddenly, the thought of her poor father crossed her mind, and she inwardly prayed that her godmother's promise of her being able to assist him out of his troubles might be realised. She then thought of her godmother's warning to leave before the hour of Twelve; and, watching the opportunity when the ladies retired, she hastened to the court-yard and was on the road home long before the clock had struck the midnight hour.

When the company re-assembled, the Prince immediately sought for Cinderella, and as she was not to be found in any of the rooms, he flew to the gate to inquire if her carriage was there ; but finding that she had departed he became quite distracted, for he had hoped to have found out who she was and where she lived. He instantly despatched messengers on horseback after the carriage, with a polite and earnest request that the lady would return for a short time; but they could nowhere find the carriage, although they had gone several miles in the direction which the coach had taken.

The Prince, in his distress, consulted the King as to what course he should pursue. The King, seeing the painful state of the Prince's mind, immediately had it announced by his chamberlains that a similar entertainment would be given the following evening; and being a kind and feeling King, and wishing to save his subjects from any increased expense for dress, they were given to understand that it was his Majesty's desire that the company should all appear in the same dresses that they wore that evening, in order, as he said, that he might recognise them again. — "Cinderella and The Glass Slipper," pp. 15-16.

The Prince had given orders to his pages to let him know instantly if they saw the beautiful Princess's carriage approaching ; and when he heard that it was really driving into the court-yard, he flew down to receive Cinderella again, and again he conducted her, with a light heart and a smiling face, to the presence of his Royal parents, who were again delighted to see their beautiful visitor. She again became the principal object of attraction and conversation, and the Prince took the first opportunity to declare himself her admirer, and to ask her to become his bride. Her reply was, that she must consult her father and friends; and he was about to beg that he might be allowed to pay his respects to them immediately, when the clock began to strike the hour of Twelve! she started up, and hastily quitted the apartment. The Prince, determined not to lose sight of her this time, followed Cinderella, for the purpose of escorting her home ; but as he hurried after her, his attention was attracted by one of her beautiful glass slippers, which had slipped off her foot in her haste to gain the outer gate. As he stooped to pick up the glass slipper, Cinderella turned into one of the passages, and he lost sight of her. When she got as far as the court-yard, the palace clock struck the last stroke of Twelve! Instantly her dress was changed into her kitchen garb, and, as she passed the outer gate, the grand coach and all were again changed to pumpkin, mushrooms, rat, mice, and lizards. — "Cinderella and The Glass Slipper," pp. 18-19.

The Perrault Context

"If you had been at the ball," said one of her sisters, "you would not have been tired with it. The finest princess was there, the most beautiful that mortal eyes have ever seen. She showed us a thousand civilities, and gave us oranges and citrons."

Cinderella seemed very indifferent in the matter. Indeed, she asked them the name of that princess; but they told her they did not know it, and that the king's son was very uneasy on her account and would give all the world to know who she was. At this Cinderella, smiling, replied, "She must, then, be very beautiful indeed; how happy you have been! Could not I see her? Ah, dear Charlotte, do lend me your yellow dress which you wear every day."

"Yes, to be sure!" cried Charlotte; "lend my clothes to such a dirty Cinderwench as you are! I should be such a fool."

Cinderella, indeed, well expected such an answer, and was very glad of the refusal; for she would have been sadly put to it, if her sister had lent her what she asked for jestingly.

The next day the two sisters were at the ball, and so was Cinderella, but dressed even more magnificently than before. The king's son was always by her, and never ceased his compliments and kind speeches to her. All this was so far from being tiresome to her, and, indeed, she quite forgot what her godmother had told her. She thought that it was no later than eleven when she counted the clock striking twelve. She jumped up and fled, as nimble as a deer. The prince followed, but could not overtake her. She left behind one of her glass slippers, which the prince picked up most carefully. She reached home, but quite out of breath, and in her nasty old clothes, having nothing left of all her finery but one of the little slippers, the mate to the one that she had dropped.

The guards at the palace gate were asked if they had not seen a princess go out. They replied that they had seen nobody leave but a young girl, very shabbily dressed, and who had more the air of a poor country wench than a gentlewoman.

When the two sisters returned from the ball Cinderella asked them if they had been well entertained, and if the fine lady had been there.

They told her, yes, but that she hurried away immediately when it struck twelve, and with so much haste that she dropped one of her little glass slippers, the prettiest in the world, which the king's son had picked up; that he had done nothing but look at her all the time at the ball, and that most certainly he was very much in love with the beautiful person who owned the glass slipper. — Charles Perrault, "Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper."

Commentary

In 1853-4 and 1864 he flattered his ambition by the issue of "George Cruikshank's Fairy Library." Unfortunately Ruskin was displeased with the earlier issues of this "library," for in 1857 he forbade his disciples to copy Cruikshank's designs for "Cinderella," "Jack and the Beanstalk" and "Tom Thumb" [sic] as being "much over-laboured and confused in line." But on July 30, 1853, Mrs. Cowden Clarke begged Cruikshank to allow her to thank him in the name of herself "and," writes she, "the other grown-up children of our family, together with the numerous little nephews and nieces who form the ungrown-up children among us, for the delightful treat you have bestowed in the shape of the 1st No. of the 'Fairy Library.'" — W. H. Chesson, pp. 155-156.

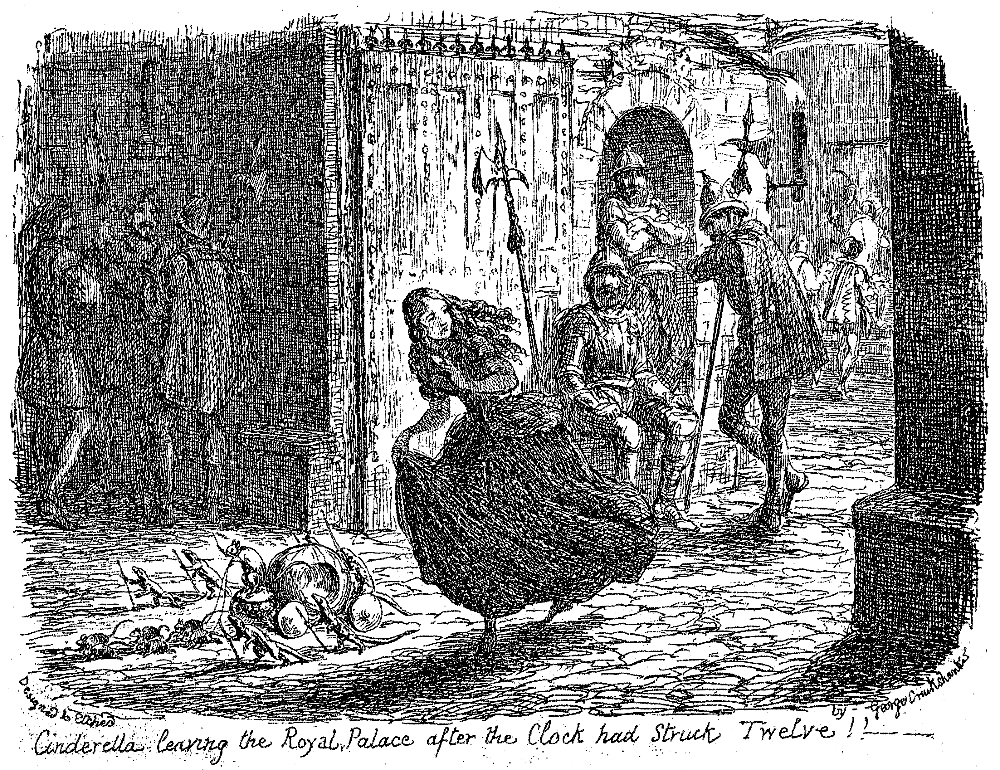

Now Cruikshank takes readers to just before midnight in the palace on the evening of the ball, the rich hangings and lighted, Italianate courtyard beyond the Prince (upper left, including a banquet in progress) being a sharp contrast to the ramshackle kitchen and the road outside that served as the backdrop for the two previous frames, when the Fairy-godmother transformed the lizards into footmen, a rat into the driver, the pumpkin into a coach, six mice into horses, and Cinderella's apron and kitchen-dress into a full-length ball-gown. Cruikshank deviates from the Perrault version in dramatising the reversion of Cinderella into a kitchen-wench and the coach and attendants into a vegetable and vermin, as will become apparent in the next frame. This is, once more, the second night of the ball, but social- and fashion-critic George Cruikshank has the court economize by the king's ordering that everybody wear the same costume as on the previous night. In the Perrault original, "Cinderella . . . [was] dressed even more magnificently than before," conspicuous consumption that Cruikshank felt needed correction.

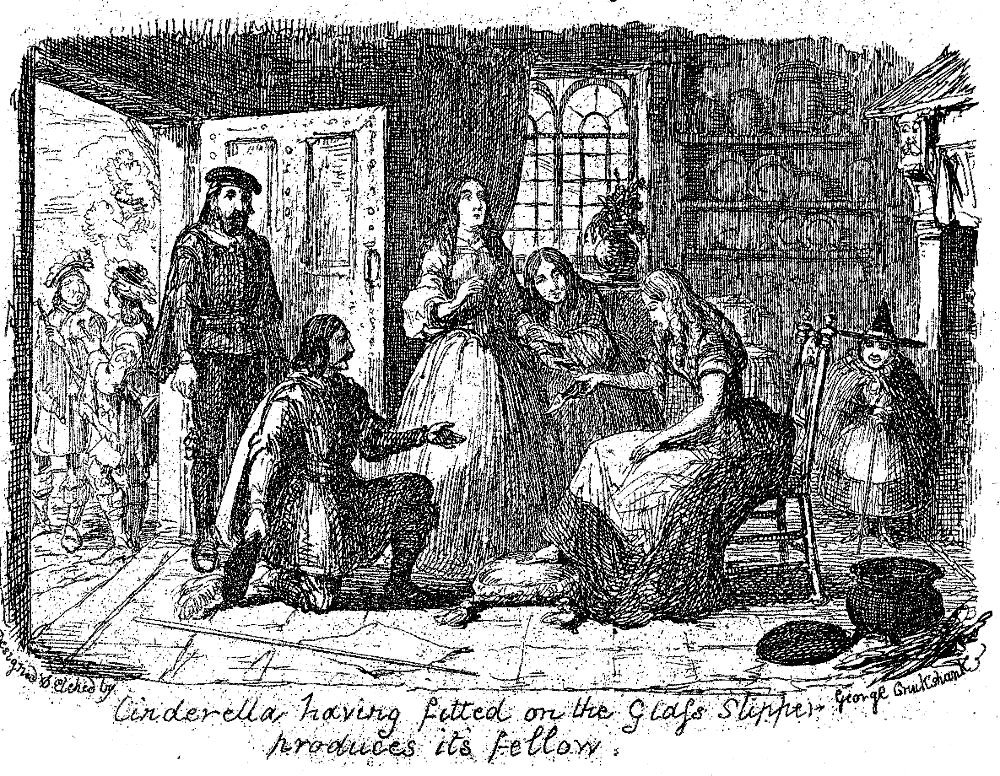

In the first panel [on the insert facing p. 19] the hopeful Prince picks up Cinderella's glass slipper. This fateful clue will allow him to search far and wide for the woman he fell in love with at the palace balls. Although he is searching for a highborn maiden who charmed the room with her finery, grace, and beauty, Cinderella loses her godmother-given trappings when the clock strikes twelve. The second image [on the same page] depicts Cinderella's transition from her ball gown to her original apparel. Slipping past the guards, Cinderella has placed the remaining glass slipper in her pocket and continues on foot.— Tulane University. "George Cruikshank — 'Cinderella'," http://library.tulane.edu/exhibits/exhibits/show/fairy_tales/george_cruikshank

Without the benefit of her fairy-guide or mentor, the protagonist commits errors in both of the frames facing page 19; in the present illustration, she has dropped a slipper in her haste; in the next, Cinderella, leaving the Royal Palace after the Clock had Struck Twelve!, having lingered too long, Cinderella is without an equipage to take her home, barely escaping from the palace before the reverse transformation is complete on the night of the second ball. An interesting touch is that the Prince has just removed his feathered cap as he stoops in order avoid having it fall off his head. A noteworthy embedded symbol is the tall candle on the enormous candelabrum which is guttering, as if suggesting that Cinderella's night of romance and dancing is on the wane, and about to sputter out as her disguise is about to collapse.

The other scenes containing the Prince

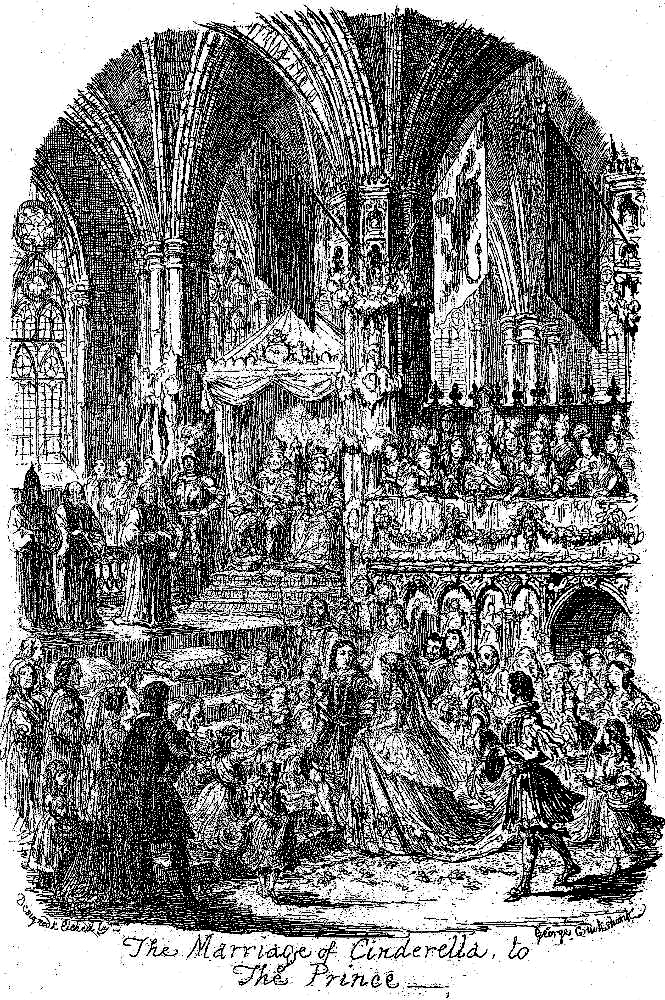

Left: George Cruikshank's second realisation of the handsome Prince, barely visible in the background, Cinderella, leaving the Royal Palace after the Clock had Struck Twelve! (1854). Centre: The finalé of the romance of the Prince and the pauper, The Marriage of Cinderella to The Prince (facing page 26). Right: Cruikshank's exciting scene in which the Prince fits the magic slipper on the heroine, with the Fairy Godmother watching the proceedings from the side, Cinderella having fitted on the Glass Slipper produces its Fellow (facing p. 20). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Related Materials

- "Frauds on the Fairies" (1 October 1853)

- Editor's Note on "Frauds on the Fairies"

- Defending the Imagination: Charles Dickens, Children's Literature, and the Fairy Tale Wars

- George Cruikshank and Charles Dickens

- Fairy Tales: Surviving the Evangelical Attack

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas; Michael Slater and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

British Library. "George Cruikshank's Fairy Library." Romantics and Victorians. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/george-cruikshanks-fairy-library

Chesson, W. H. "From George Cruikshank's Fairy Library, 'Cinderella,' 1854." George Cruikshank. London: Duckworth, 1920.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Cruikshank, George. Cinderella and The Glass Slipper. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. The third volume in George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. London: David Bogue, 1854. (Price one shilling) 10 etchings on 6 tipped-in pages, including frontispiece.

Cruikshank, George. George Cruikshank's Fairy Library: "Hop-O'-My-Thumb," "Jack and the Bean-Stalk," "Cinderella," "Puss in Boots". London: George Bell, 1865.

Dickens, Charles. "Frauds on the Fairies." Household Words. A Weekly Journal. Conducted by Charles Dickens.. 1 October 1853. No. 184, Vol. VIII. Pp. 97-100.

Guildhall Library blog. "A Gem from Guildhall Library's Shelves: George Cruikshank's Fairy Library by George Cruikshank published by Routledge in London (c. 1870)." 8 August 2014. https://guildhalllibrarynewsletter.wordpress.com/2016/08/08/a-gem-from-guildhall-librarys-shelves-george-cruikshanks-fairy-library-by-george-cruikshank-published-by-routledge-in-london-c1870/

Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University. "George Cruikshank." http://library.tulane.edu/exhibits/exhibits/show/fairy_tales/george_cruikshank

Hubert, Judd D. "George Cruikshank's Graphic and Textual Reactions to Mother Goose." Marvels & Tales, Volume 25, Number 2, 2011 (pp. 286-297). Project Muse. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/462736/pdf

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Kotzin, Michael C. Dickens and the Fairy Tale. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1972.

Perrault, Charles. "Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper." Fairy Tales and Other Traditional Stories. Lit2Go. http://etc.usf.edu/lit2go/68/fairy-tales-and-other-traditional-stories/5089/jack-and-the-bean-stalk/

Schlicke, Paul. "

Vogler, Richard, The Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. New York: Dover, 1979.

Last modified 2 July 2017