Captain Cuttle's Bright Idea

Harold Copping

1924

Colour lithography

17/9 cm. by 12.4 cm.

From Character Sketches from Dickens, facing p. 84 (illustrating Dombey and Son)

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Harold Copping —> Next]

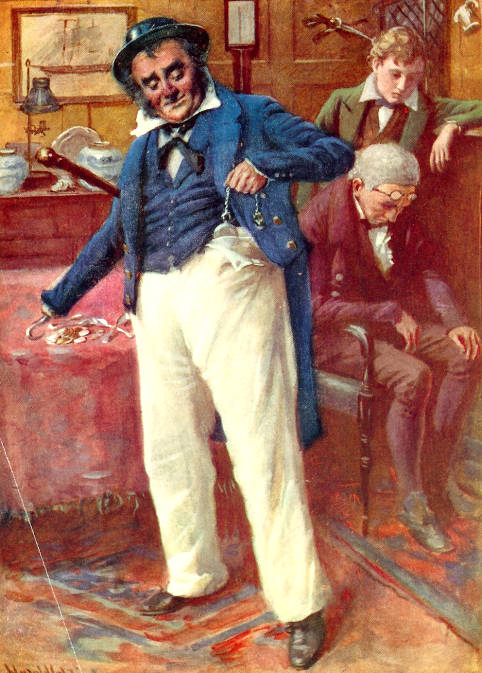

Captain Cuttle's Bright Idea

Harold Copping

1924

Colour lithography

17/9 cm. by 12.4 cm.

From Character Sketches from Dickens, facing p. 84 (illustrating Dombey and Son)

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Of Dombey and Son Dickens said after its completion that he considered that if any of his books "are read years hence, 'Dombey' will be remembered as among the best of them." That might have been said of most of them. But there is no doubt Dickens was proud of "Dombey," and we know how little Paul appealed to him, and how affected he was when writing his death scene. However, he had a still more favourite book in David Copperfield.

His aim in writing Dombey and Son was to show the humbling of pride and the awakening of parental love, and the book is a great contribution to the subject. It is as packed full of real characters as any of his books, whilst the story has more dramatic interest than most.

Captain Cuttle is a veritable triumph of creative power, and although the scene we give is pleasant and characteristic, it hardly does justice to the man who made immortal the phrase "when found, make a note of it" (p. 82).

The real Wooden Shipman, the chandlery owned by Walter Gay's uncle, Solomon Gillis, stood at No. 157 Leadenhall Street, opposite East India House, London; "The firm removed to Minories on the demolition of their Leadenhall Street premises, and the effigy [of the Little Midshapman that Dickens was accustomed to pat affectionately whenever he walked from Covent Garden past East India House] is carefully preserved from the weather inside their office at No. 123" (p. 129) wrote Dickensian editor Walter Dexter in 1929. The early-nineteenth-century wooden figure now resides in the Dickens House Museum, Doughty Street, London. However, the Dickens character most closely associated with the nautical instruments business is not the proprietor, but Captain Cuttle, the crusty retired sailor who ineffectually attempts to bail Sol Gillis of out a debt of "three hundred and seventy odd" pounds in Dombey and Son, chapter 9, "In Which The Wooden Shipman Gets into Trouble" (originally in Part 3, December 1846):

But when Walter told him what was really the matter, Captain Cuttle, after a moment's reflection, started up into full activity. He emptied out of a little tin canister, on the top shelf of the cupboard, his whole stock of ready money (amounting to thirteen pounds and half-a-crown), which he transferred to one of the pockets of his square blue coat: further enriched that repository with the contents of his plate chest, consisting of two withered atomies of tea-spoons and an obsolete pair of knock-kneed sugar-tongs; pulled up his immense double-cased silver watch from the depths in which it reposed, to assure himself that that valuable was sound and whole; reattached the hook to his right wrist; and seizing the stick covered over with nobs, bade Walter come along.

At their destination, the back parlour of the offices of The Wooden Midshipman, Captain Cuttle poured out his pockets and displayed the contents for agent, Mr. Brogley, but to no avail. As in Phiz's illustration "Captain Cuttle Consoles His Friend," the old sailor then attempts (on the reader's behalf) to get to the bottom of the mysterious bond that imperils his friends' very existence. Sol admits that the debt is based on a bond that served as security for a debt contracted by Walter's father many years before. Whereas Phiz is as interested in the exotic and nautical bric-a-brac of the parlour as he is in the typical youthful protagonist of Dickens's early novels (Walter Gay), the uncle, the sailor, and the debt-collector (trying to master the intricacies of a sextant in the background), Copping captures Captain Cuttle in motion. He is shown drawing his enormous chronometer from his trouser pocket to add to the pile of money and silver spoons on the table, left. As in Phiz's original, in Copping's illustration a dejected Sol Gillis sits downcast in his chair, his glasses sitting on his forehead and below his grey Welsh wig, while Walter attempts to comfort him. The bulk of the Captain in blue and white dominates the rosey-hued room and squeezes the uncle and nephew out of the frame, as if to suggest the process whereby all too often in Dickens's novels the minor comic characters crowd the pallid principals out of the mind's eye. Missing, probably because they would have disturbed this focus and cluttered the scene, are Sol's footstool and Mr. Brogley. Further, whereas Phiz has exaggerated the Captain's red nose and girth, Copping has made him less of a caricature and a more individualized character, his gaze directed at his constant companion, the old silver pocket-watch, rather than (as in Phiz's plate) Sol Gillis, the object of selfless philanthropy.

Dickens, Mary Angela, Percy Fitzgerald, Captain Edric Vredenburg, and Others. Illustrated by Harold Copping with eleven coloured lithographs. Children's Stories from Dickens. London: Raphael Tuck, 1893.

Dickens, Mary Angela [Charles Dickens' grand-daughter]. Dickens' Dream Children. London, Paris New, York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, Ltd., 1924.

Created 6 March 2009 Last updated 21 September 2023