The Night of the Return

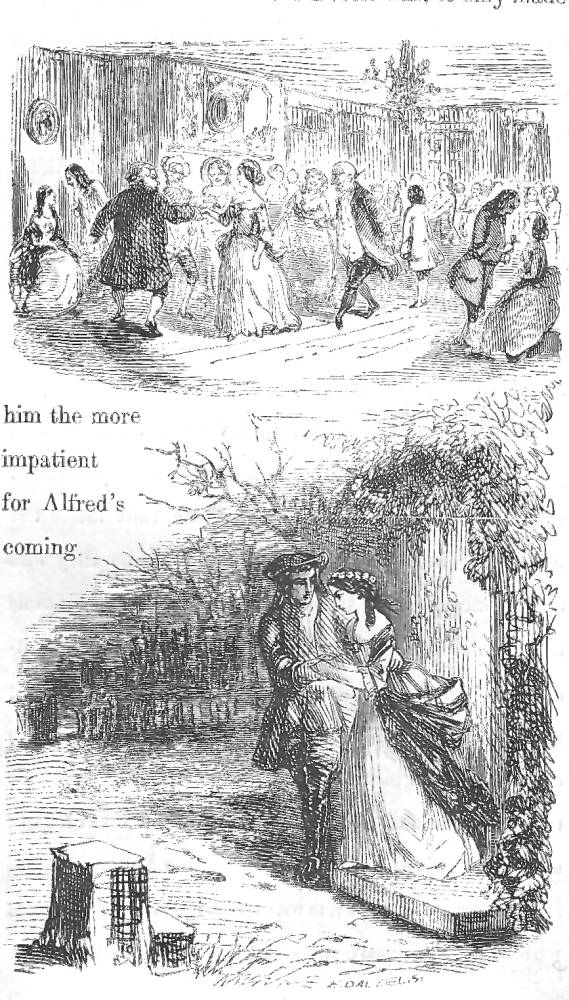

John Leech; engraver, Frederick Dalziel

1846

Wood engraving

12.2 high by 7 cm wide (4 ¾ by 2 ¾ inches), vignetted.

Full-page illustration for Dickens's The Battle of Life: "Part the Second," 114.

Click on image to enlarge it

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.].

Surrounding and Embedded Text

Hot and breathless as the Doctor was, it only made him the more impatient for Alfred's coming. [114]

Passage Illustrated; Two Scenes, but only one reified in the Text

Now the music struck up, and the dance commenced. The bright fire crackled and sparkled, rose and fell, as though it joined the dance itself, in right good fellowship. Sometimes, it roared as if it would make music, too. Sometimes, it flashed and beamed as if it were the eye of the old room: it winked, too, sometimes, like a knowing patriarch, upon the youthful whisperers in corners. Sometimes, it sported with the holly-boughs; and, shining on the leaves by fits and starts, made them look as if they were in the cold winter night again, and fluttering in the wind. Sometimes its genial humour grew obstreperous, and passed all bounds; and then it cast into the room, among the twinkling feet, with a loud burst, a shower of harmless little sparks, and in its exultation leaped and bounded, like a mad thing, up the broad old chimney. [pp. 105-106]

It was an old custom among them, indeed, to do so, and to pair off, in like manner, at dinners and suppers; for they were excellent friends, and on a footing of easy familiarity. Perhaps the false Craggs and the wicked Snitchey were a recognised fiction with the two wives, as Doe and Roe, incessantly running up and down bailiwicks, were with the two husbands: or, perhaps the ladies had instituted, and taken upon themselves, these two shares in the business, rather than be left out of it altogether. But, certain it is, that each wife went as gravely and steadily to work in her vocation as her husband did in his, and would have considered it almost impossible for the Firm to maintain a successful and respectable existence, without her laudable exertions.

But, now, the Bird of Paradise was seen to flutter down the middle; and the little bells began to bounce and jingle in poussette; and the Doctor’s rosy face spun round and round, like an expressive pegtop highly varnished; and breathless Mr. Craggs began to doubt already, whether country dancing had been made ‘too easy,’ like the rest of life; and Mr. Snitchey, with his nimble cuts and capers, footed it for Self and Craggs, and half-a-dozen more.

Now, too, the fire took fresh courage, favoured by the lively wind the dance awakened, and burnt clear and high. It was the Genius of the room, and present everywhere. It shone in people’s eyes, it sparkled in the jewels on the snowy necks of girls, it twinkled at their ears as if it whispered to them slyly, it flashed about their waists, it flickered on the ground and made it rosy for their feet, it bloomed upon the ceiling that its glow might set off their bright faces, and it kindled up a general illumination in Mrs. Craggs’s little belfry.

Now, too, the lively air that fanned it, grew less gentle as the music quickened and the dance proceeded with new spirit; and a breeze arose that made the leaves and berries dance upon the wall, as they had often done upon the trees; and the breeze rustled in the room as if an invisible company of fairies, treading in the foot-steps of the good substantial revellers, were whirling after them. Now, too, no feature of the Doctor’s face could be distinguished as he spun and spun; and now there seemed a dozen Birds of Paradise in fitful flight; and now there were a thousand little bells at work; and now a fleet of flying skirts was ruffled by a little tempest, when the music gave in, and the dance was over.

Hot and breathless as the Doctor was, it only made him the more impatient for Alfred’s coming.the distance, as she slowly made her way into the crowd, and passed out of their view. ["Part the Second," pp. 111-114]

Relevant Illustrations from the later editions (1876, 1878, 1893, 1910)

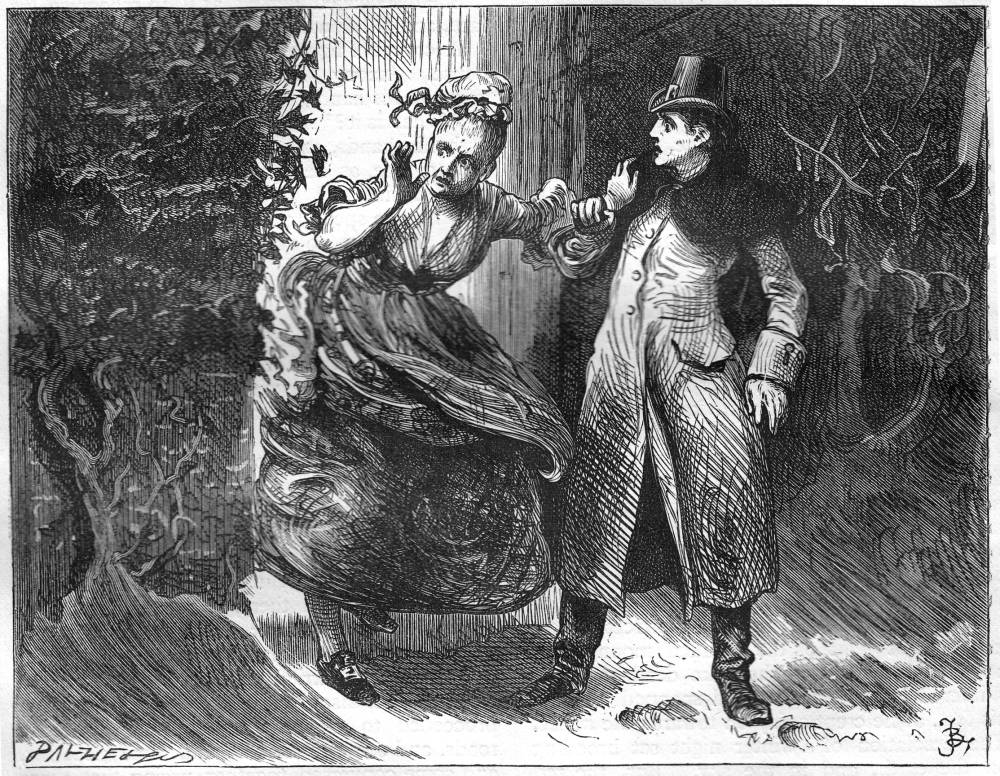

Left: Doyle's dramatic illustration of the confusion attendant upon the discovery of Marion's disappearance, Part the Second. Centre: Leech's dual illustration of the Christmas party and the supposed elopement, The Night of the Return. Right: Harry Furniss's intimation that Michael Warden and Marion are eloping, For Alfred's Sake (1910).

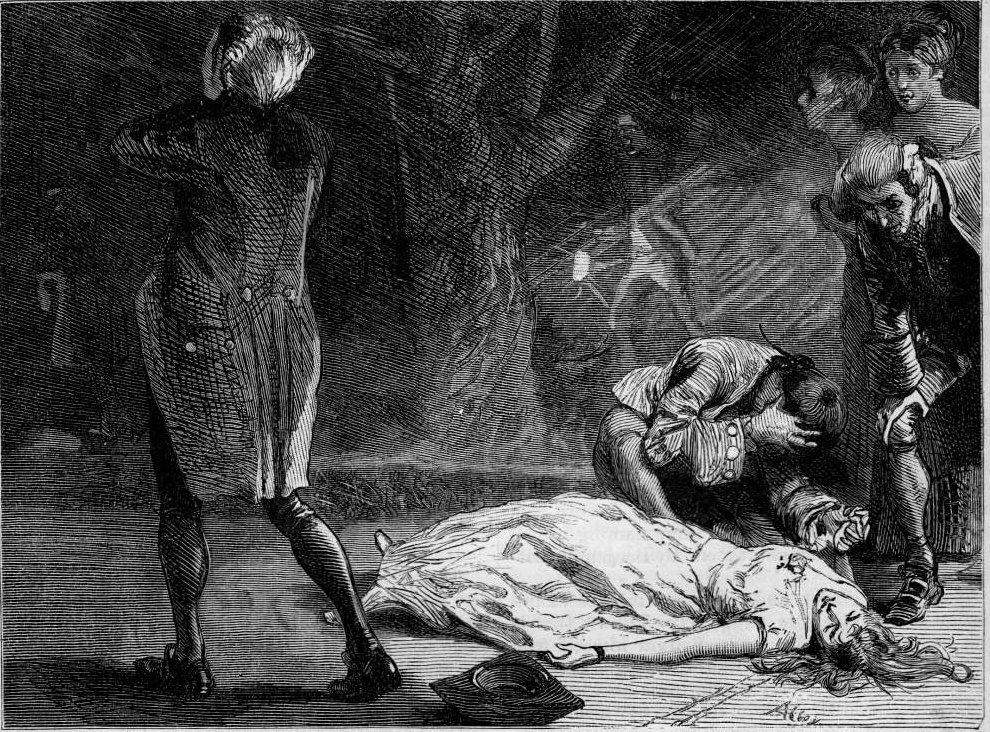

Above: Abbey's 1876 wood-engraving of the scene outside Dr. Jeddler's home as Alfred discovers that Marion is missing, And sunk down in his former attitude, clasping one of Grace's cold hands in his own.

Above: Barnard's wood-engraving of the scene in which Alfred, just arrived, learns that Marion has vanished into the night: "What is the matter?" he exclaimed. "I don't know. I — I am afraid to think. Go back. Hark!" (1878).

Commentary: An Invented Scene and a Realisation for the Illustration

Although Dickens has furnished his illustrator with ample text to describe Dr. Jeddler's dance, he only intimates through the dialogue between the lawyers that their client is "safe away" (107), and gives no intimation whatsoever that Michael Warden will elope to the Continent with Marion Jeddler. The larger, lower register, showing the aristocratic youth leading away a fashionably attired young woman (wearing a wreath in her hair) — from the very porch depicted in The Secret Interview on page 96 — is entirely Leech's invention. Only much later does Dickens provide the answer to her mysterious disappearance.

Robert L. Patten writes,

Leech's full-page illustration confines the Christmas party, almost as an afterthought, to a third of the design, at the top, while two-thirds are occupied with Marion, still wearing the pre-marital wreath in her hair, who is exiting from the lighted house in the arms of her lover. But of course Leech is wrong; she didn't depart with Warden. And Dickens left the image uncorrected. Perhaps because in the context of the Christmas dance and Alred's return, others, including the reader, might suppose that to be the case. If Dickens tolerated this fundamental error, might it be because he accepted the possibility, as nearly was the case in The Chimes, that what was expected by characters and readers deserved illustrating as much as what actually happened? That supposition would play havoc with assumptions that all illustrations have to conform exactly to what the text says, and never hint at alternative possibilities. [224-225]

Related Materials

- The Dedication, Illustrations, and Illustrators for The Battle of Life (1846)

- Robert L. Patten's Dickens, Death and Christmas, Chapter 8: "Chirping" and Pantomime, and Chapter 9: Battling for His Life

- Pears' Centenary Edition of The Battle of Life (1912)

- The Christmas Books of Charles Dickens

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s single illustration for The Battle of Life (1867)

- A. E. Abbey's Household Edition illustrations for The Christmas Books (1876)

- Fred Barnard's Household Edition illustrations for The Christmas Books (1878)

- Harry Furniss's illustrations for Dickens's The Battle of Life (1910)

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. Engraved by J. Thompson, Dalziel, T. Williams, and Green. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846.

Morley, Malcolm. "The Battle of Life in the Theatre." Dickensian 48 (1 January 1952): 76.

Patten, Robert L. Chapter 9, "Battling for his Life." Dickens, Death, and Christmas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023. 200-233. [Review]

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustration

John

Leech

Next

Created 20 February 2001

Last updated 3 June 2024