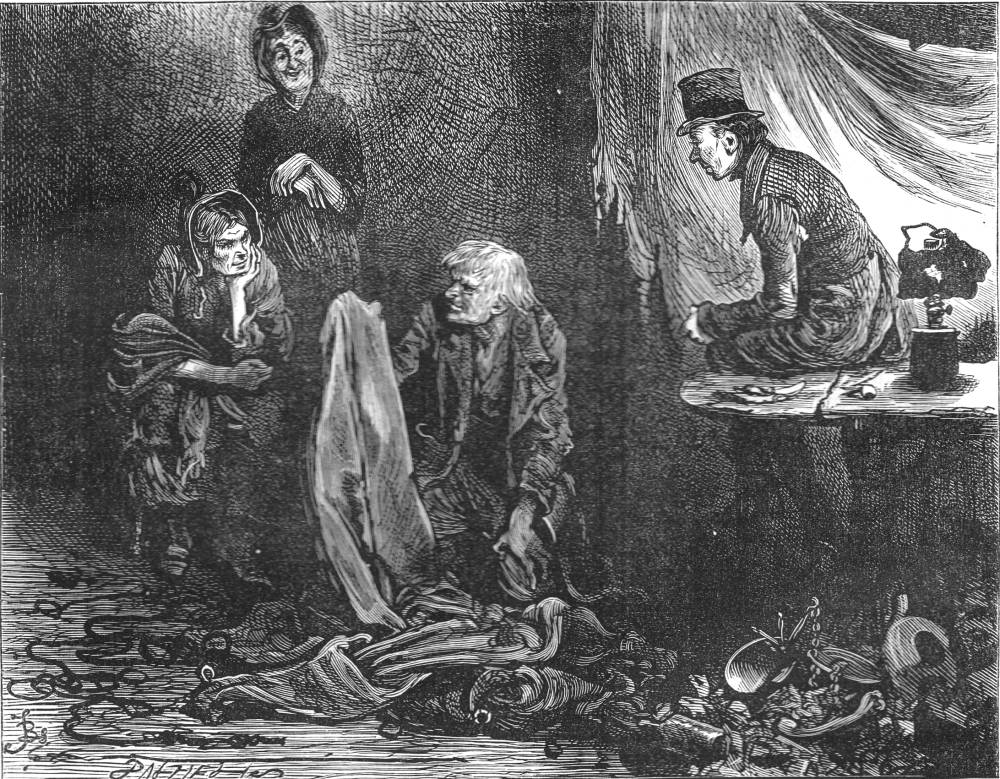

"What do you call this?" said Joe. "Bed-curtains?" by Fred Barnard. The British Household Edition (1878) of Dickens's Christmas Books, p. 32. Engraved by one of the Dalziels, and signed "FB" lower right. 10.7 by 13.8 cm (4 ¼ by 5 ⅜ inches), framed. A Christmas Carol, "Stave Four: The Last of the Spirits." Barnard's sixth and final Carol illustration depicts Scrooge's charlady, Mrs. Dilber, and his laundrywoman joining with the respectably dressed undertaker's man to pawn Scrooge's portable belongings. In the process, the women reveal how they really felt about him. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Barnard's final illustration compared to that by Sol Eytinge, Jr., and the final Abbey plate.

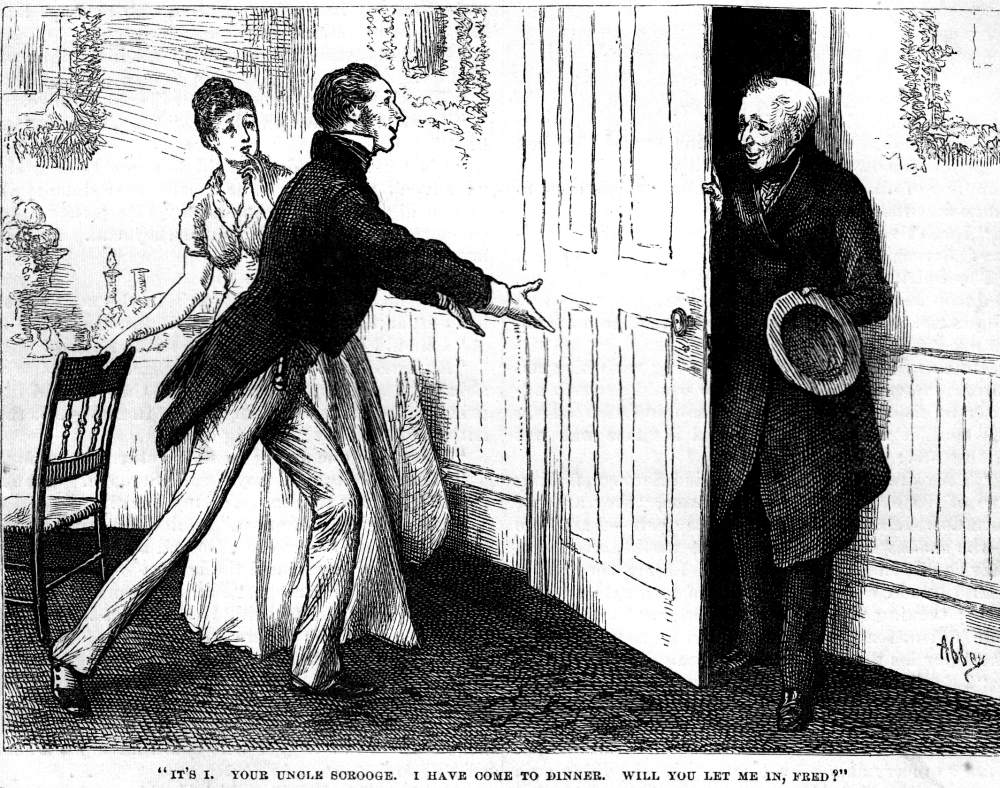

In his original 1843 sequence of eight illustrations, John Leech did not provide a picture of Scrooge's visit to the the rag-and-bone shop to watch the people whom he had known and taken for granted to give him domestic service to dispose of his clothing, personal belongings, and even his sheets. In his sequence of six illustrations for the 1876 Harper and Brothers Household Edition of Christmas Stories, American artist E. A. Abbey eschews the socially provocative aspects of A Christmas Carol as he focuses on the more genial aspects of Scrooge's redemption, concluding with his arrival on nephew Fred's doorstep as he pleads to be admitted to the family he had formerly spurned, and to participate in the family holiday that he has has ridiculed as "humbug."

Fred Barnard and Sol Eytinge, Jr., however, almost seem to relish the grotesquerie and sordidness of Old Joe's pawnshop. The rag-and-bone business in the depths of the hellish London slums would seem to be the complete antithesis of the Royal Stock Exchange, depicted in the previous scene: in fact, despite the binary opposites of light and dark, rich and poor, and respectability and corruption, both plates depict places of business that are necessary corollaries of the capitalist system of which Scrooge has heretofore been a leading exponent. Joe, like Marley and Scrooge, is a good man of business who knows that the value of a thing is only what somebody is prepared to pay for it. In Eytinge's Old Joe, the pawnbroker, a hideous, hook-nosed old rascal, is examining the bedsheets. He is presiding over a shop filled with rags, rather than, as in Barnard's woodcut, old metal, as Dickens mentions piles of various metal objects. The dialogue between the unsavoury proprietor of the foul shop, the undertaker's man in black (right), and the women (left) which both Sol Eytinge, Jr., in 1868 and Fred Barnard in 1878 had in mind is this:

Two concluding illustrations of scenes indicative of Scrooge's redemption: Left: Eytinge's Old Joe (Stave Four). Right: Abbey's "It's I. Your Uncle Scrooge. . . . ." (Stave Five). [Click on each image to enlarge it.]

They left the busy scene, and went into an obscure part of the town, where Scrooge had never penetrated before, although he recognised its situation, and its bad repute. The ways were foul and narrow; the shops and houses wretched; the people half-naked, drunken, slipshod, ugly. Alleys and archways, like so many cesspools, disgorged their offenses of smell, and dirt, and life, upon the straggling streets; and the whole quarter reeked with crime, with filth, and misery.

Far in this den of infamous resort, there was a low-browed, beetling shop, below a pent-house roof, where iron, old rags, bottles, bones, and greasy offal, were bought. Upon the floor within, were piled up heaps of rusty keys, nails, chains, hinges, files, scales, weights, and refuse iron of all kinds. Secrets that few would like to scrutinise were bred and hidden in mountains of unseemly rags, masses of corrupted fat, and sepulchres of bones. Sitting in among the wares he dealt in, by a charcoal stove, made of old bricks, was a grey-haired rascal, nearly seventy years of age; who had screened himself from the cold air without, by a frowsy curtaining of miscellaneous tatters, hung upon a line; and smoked his pipe in all the luxury of calm retirement.

Scrooge and the Phantom came into the presence of this man, just as a woman with a heavy bundle slunk into the shop. But she had scarcely entered, when another woman, similarly laden, came in too; and she was closely followed by a man in faded black, who was no less startled by the sight of them, than they had been upon the recognition of each other. After a short period of blank astonishment, in which the old man with the pipe had joined them, they all three burst into a laugh.

"Let the charwoman alone to be the first!" cried she who had entered first. "Let the laundress alone to be the second; and let the undertaker's man alone to be the third. Look here, old Joe, here's a chance. If we haven't all three met here without meaning it!"

"You couldn't have met in a better place," said old Joe, removing his pipe from his mouth. "Come into the parlour. You were made free of it long ago, you know; and the other two an't strangers. Stop till I shut the door of the shop. Ah. How it skreeks. There an't such a rusty bit of metal in the place as its own hinges, I believe; and I'm sure there's no such old bones here, as mine. Ha, ha! We're all suitable to our calling, we're well matched. Come into the parlour. Come into the parlour."

The parlour was the space behind the screen of rags. The old man raked the fire together with an old stair-rod, and having trimmed his smoky lamp (for it was night), with the stem of his pipe, put it in his mouth again.

While he did this, the woman who had already spoken threw her bundle on the floor, and sat down in a flaunting manner on a stool; crossing her elbows on her knees, and looking with a bold defiance at the other two.

"What odds then. What odds, Mrs. Dilber." said the woman. "Every person has a right to take care of themselves. He always did."

"That's true, indeed," said the laundress. "No man more so."

"Why then, don't stand staring as if you was afraid, woman; who's the wiser? We're not going to pick holes in each other's coats, I suppose?"

"No, indeed," said Mrs. Dilber and the man together. "We should hope not."

"Very well, then!" cried the woman. "That's enough. Who's the worse for the loss of a few things like these? Not a dead man, I suppose."

"No, indeed," said Mrs. Dilber, laughing.

"If he wanted to keep them after he was dead, a wicked old screw," pursued the woman, "why wasn't he natural in his lifetime? If he had been, he'd have had somebody to look after him when he was struck with Death, instead of lying gasping out his last there, alone by himself."

"It's the truest word that ever was spoke," said Mrs. Dilber. "It's a judgment on him."

"I wish it was a little heavier judgment," replied the woman; "and it should have been, you may depend upon it, if I could have laid my hands on anything else. Open that bundle, old Joe, and let me know the value of it. Speak out plain. I'm not afraid to be the first, nor afraid for them to see it. We know pretty well that we were helping ourselves, before we met here, I believe. It's no sin. Open the bundle, Joe."

But the gallantry of her friends would not allow of this; and the man in faded black, mounting the breach first, produced his plunder. It was not extensive. A seal or two, a pencil-case, a pair of sleeve-buttons, and a brooch of no great value, were all. They were severally examined and appraised by old Joe, who chalked the sums he was disposed to give for each upon the wall, and added them up into a total when he found there was nothing more to come.

"That's your account," said Joe, "and I wouldn't give another sixpence, if I was to be boiled for not doing it. Who's next?"

Mrs. Dilber was next. Sheets and towels, a little wearing apparel, two old-fashioned silver teaspoons, a pair of sugar-tongs, and a few boots. Her account was stated on the wall in the same manner.

"I always give too much to ladies. It's a weakness of mine, and that's the way I ruin myself," said old Joe. "That's your account. If you asked me for another penny, and made it an open question, I'd repent of being so liberal and knock off half-a-crown."

"And now undo my bundle, Joe," said the first woman.

Joe went down on his knees for the greater convenience of opening it, and having unfastened a great many knots, dragged out a large and heavy roll of some dark stuff.

"What do you call this?" said Joe. "Bed-curtains?"

"Ah!" returned the woman, laughing and leaning forward on her crossed arms. "Bed-curtains!"

"You don't mean to say you took 'em down, rings and all, with him lying there?" said Joe.

"Yes, I do," replied the woman. "Why not?" ["Stave Four"; Household Edition, pp. 29-30]

Technically, the bartering transpires in the context of old Joe's parlour, which is separated from the outer shop by a screen of rags, so that both illustrators have conflated the two rooms, probably to emphasize the carrion nature of the establishment. Neither felt inclined to realise the extreme unpleasantness involved in "masses of corrupted fat, and sepulchres of bones" (29). As for the description of the characters involved, Dickens has given his illustrators little enough to work with, other than Joe's advanced age, pipe, and grey hair. On the other hand, Barnard employs the "frouzy curtaining of miscellaneous tatters" (29) and intense cross-hatching to create a nightmarish atmosphere. Eytinge uses the faces alone to convey the scene's dominant feeling, which is not the earnest conducting of business we see in Barnard's version but in Eytinge's a joyous glee at finally having bested the miser, as the women and old Joe on bended knee carefully examine the fabric while the undertaker's man looks on from above.

The significant difference between the two treatments is Eytinge's caricaturing of old Joe versus Barnard's highly realistic social commentary, reminiscent of his early work for such British periodicals as The Illustrated London News. In the next decade, Barnard collaborated with G. R. Sims on a series entitled How the Poor Live for the Pictorial World (1883). Also relevant to this vulture-like gathering at Old Joe's are Barnard's large-scale canvasses of social comment upon the urban scene as Saturday Night in the East End (1876), which shares with this small-scale picture a certain infernal or Dantesque quality.

However, none of Barnard's participants in the post-mortem bartering could justly be designated an "obscene demon" (30); they are merely conductors of business and agents of commerce, not so different (but for their less than elegant attire) from the businessmen of the previous scene. Scrooge, a dealer in commodities, has himself in death become a commodity, Barnard implies. The triumph of the scene, a parody of Twelfth Night celebrations and "a mock Adoration on a future Twelfth Night Epiphany" (Robert L. Patten, Charles Dickens and His Publishers, 187) is the artist's ability to throw over the frowsy and unpleasant moment of choric commentary a certain vividness that transmutes the unsavoury side of the capitalistic enterprise into the engagingly beautiful as we and Scrooge observe the commercialization of Scrooge's belongings. Here, then, Barnard as social commentator crystallises the dreamer's "vague uncertain horror" (27) at the beginning of Stave Four into a powerfully conceived night scene in what Robert L. Patten (1978) appropriately terms "the city's colon" (186).

Text, scanned images, and formatting by Philip V. Allingham. Earlier formatting, colour correction, and linking by George P. Landow.[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Cook, James. Bibliography of the Writings of Dickens. London: Frank Kerslake, 1879. As given in the Publishers' Circular The English Catalogue of Books.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People [Seven Sketches from "Our Parish"]. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of the 1867 Ticknor & Fields volume].

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol — A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1868.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by A. E. Abbey. The Household Edition. 17 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876. III: 11-39.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878. XVII: 1-37.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by John Leech. Charles Dickens: The Christmas Books. Ed. Michael Slater. 2 vols. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. Vol. 1: 38-134.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Parker, David. "Christmas Books and Stories, 1844 to 1854." Christmas and Charles Dickens. New York: AMS Press, 2005. Pp. 221-282.

Patten, Robert L. Charles Dickens and His Publishers. University of California at Santa Cruz. The Dickens Project, 1991. rpt. from Oxford U. p., 1978.

Patten, Robert L. Chapter 6, "Marley Was Dead." Dickens, Death, and Christmas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023. 74-126. ISBN 978-0-19-286266-2. [Review]

Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings by Fred Barnard, Hablot K. Browne (Phiz), J. Mahoney, Charles Green, A. B. Frost, Gordon Thomson, J. McL. Ralston, H. French, E. G. Dalziel, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes; Printed from the Original Woodblocks Engraved for "The Household Edition". London: Chapman and Hall, 1908.

Slater, Michael. "Introduction to A Christmas Carol." Dickens's Christmas Books. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. Vol. 1: 33-44.

Slater, Michael. "A Note on the Text and Annotation." "Notes to A Christmas Carol." Dickens's Christmas Books. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. Vol. 1: xxvii-xxviii; 257-261

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Created 15 October 2015

Last modified 10 June 2024