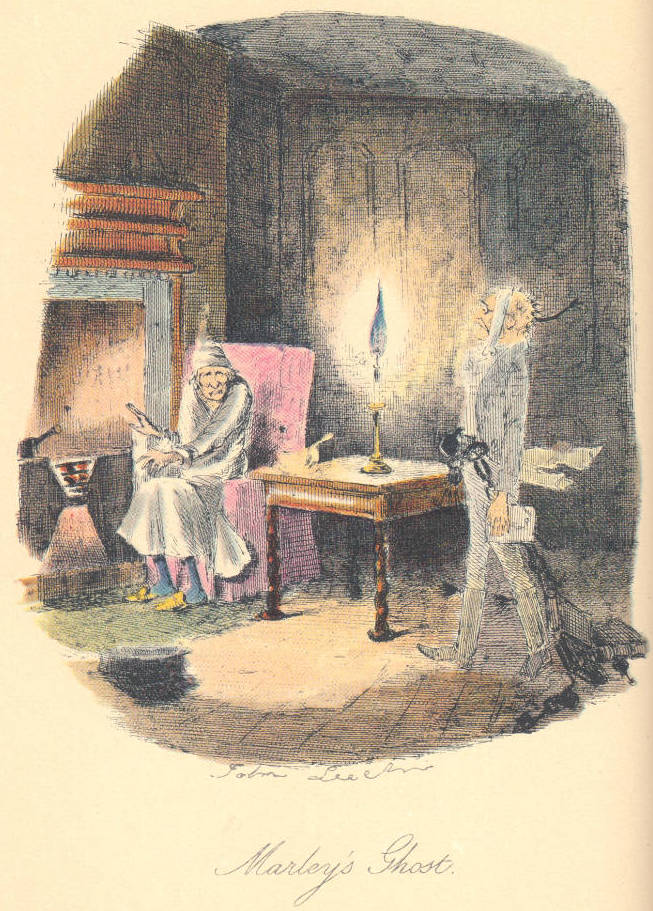

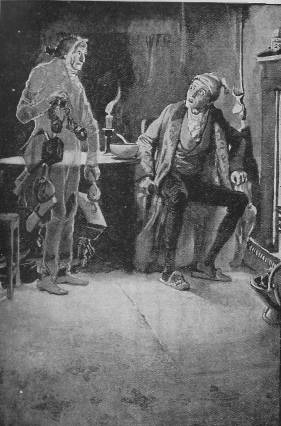

Marley's Ghost

Fred Barnard

13.9 x 10.7 cm (5 ¼ by 4 inches), framed.

Fourth illustration for Dickens's A Christmas Carol, "Stave the First," Household Edition (1878), Vol. XVII, p. 8.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.