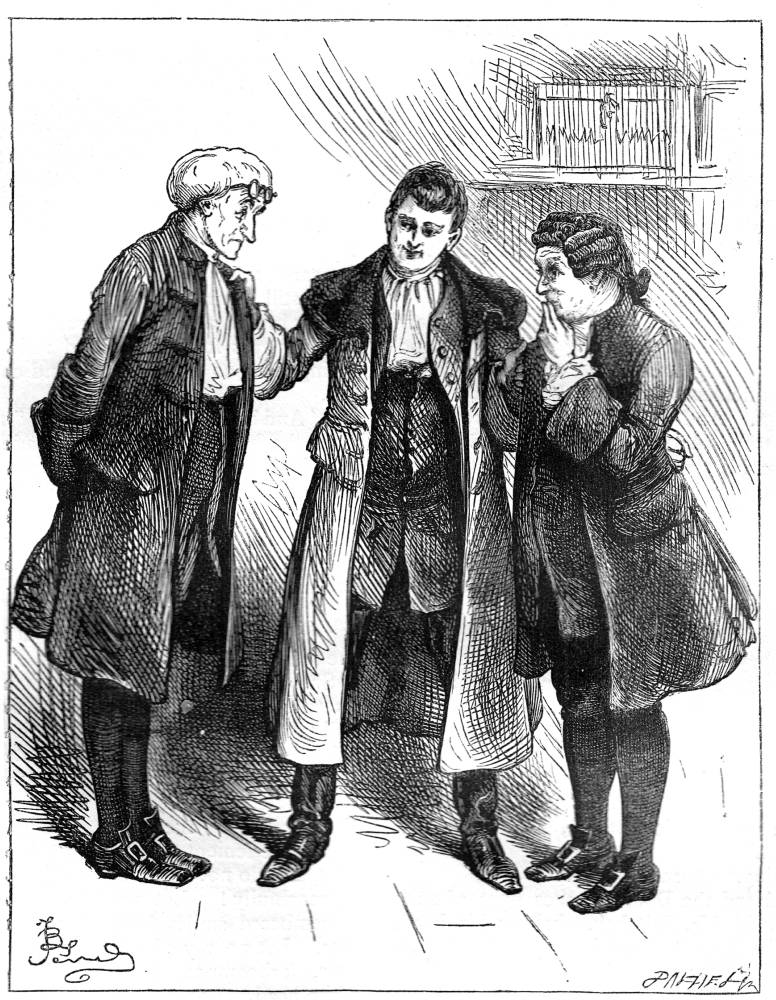

"I think it will be better not to hear this, Mr. Craggs?"

Fred Barnard

1878

13.8 by 10.7 cm (5 ⅜ by 4 ¼ inches), framed.

See commentary below

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Fred Barnard —> Illustrations of The Christmas Books —> Next]

"I think it will be better not to hear this, Mr. Craggs?"

Fred Barnard

1878

13.8 by 10.7 cm (5 ⅜ by 4 ¼ inches), framed.

See commentary below

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham.

You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.

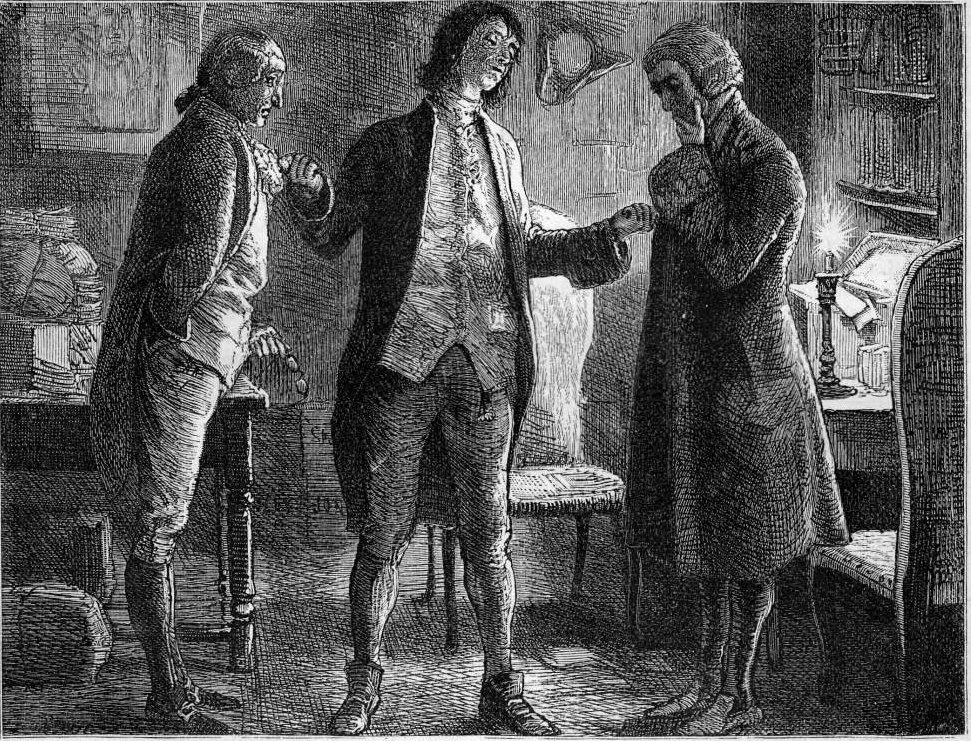

Here, nearly three years’ flight had thinned the one and swelled the other, since the breakfast in the orchard; when [the country lawyers Snitchey and Craggs] sat together in consultation at night.

Not alone; but, with a man of about thirty, or that time of life, negligently dressed, and somewhat haggard in the face, but well-made, well-attired, and well-looking, who sat in the armchair of state, with one hand in his breast, and the other in his dishevelled hair, pondering moodily. Messrs. Snitchey and Craggs sat opposite each other at a neighbouring desk. One of the fireproof boxes, unpadlocked and opened, was upon it; a part of its contents lay strewn upon the table, and the rest was then in course of passing through the hands of Mr. Snitchey; who brought it to the candle, document by document; looked at every paper singly, as he produced it; shook his head, and handed it to Mr. Craggs; who looked it over also, shook his head, and laid it down. Sometimes, they would stop, and shaking their heads in concert, look towards the abstracted client. And the name on the box being Michael Warden, Esquire, we may conclude from these premises that the name and the box were both his, and that the affairs of Michael Warden, Esquire, were in a bad way.

"That's all," said Mr. Snitchey, turning up the last paper. "Really there’s no other resource. No other resource."

"All lost, spent, wasted, pawned, borrowed, and sold, eh?" said the client, looking up.

"All," returned Mr. Snitchey.

"Nothing else to be done, you say?"

"Nothing at all."

The client bit his nails, and pondered again.

"And I am not even personally safe in England? You hold to that, do you?"

"In no part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland," replied Mr. Snitchey.

"A mere prodigal son with no father to go back to, no swine to keep, and no husks to share with them? Eh?" pursued the client, rocking one leg over the other, and searching the ground with his eyes.

Mr. Snitchey coughed, as if to deprecate the being supposed to participate in any figurative illustration of a legal position. Mr. Craggs, as if to express that it was a partnership view of the subject, also coughed.

"Ruined at thirty!" said the client. "Humph!"

"Not ruined, Mr. Warden," returned Snitchey. "Not so bad as that. You have done a good deal towards it, I must say, but you are not ruined. A little nursing — "

"A little Devil," said the client.

"Mr. Craggs," said Snitchey, "will you oblige me with a pinch of snuff? Thank you, sir."

As the imperturbable lawyer applied it to his nose with great apparent relish and a perfect absorption of his attention in the proceeding, the client gradually broke into a smile, and, looking up, said:

"You talk of nursing. How long nursing?"

"How long nursing?" repeated Snitchey, dusting the snuff from his fingers, and making a slow calculation in his mind. "For your involved estate, sir? In good hands? S. and C.'s, say? Six or seven years." ["Part the Second," 1846 Edition, pp. 59-62]

When The Battle of Life first appeared, it was accompanied by John Leech's illustration of spendthrift aristocrat Michael Warden's consulting the attorneys Snitchey and Craggs. The image is neither proleptic (shown in advance of the text) or analeptic (shown after the passage realised), but embedded in the letterpress so that the reader confronts the image and the passage simultaneously, and therefore studies the expressions and poses of the three characters in two media at once.

Such, however, is not the case in either of the illustrations in the later American or the British Household Editions, both of which capture essentially the same moment, that is, when Michael Warden confesses his plan to elope with Marion Jeddler, with whom a horseback riding accident has brought him into close contact. In the passage below, the lengthy titles of the Abbey (1876) and Barnard (1878) illustrations have been italicized. In Barnard's illustration one finds the likenesses of client and attorneys analeptically positioned, forcing the reader to re-evaluate the passage in light of a second "reading" of it in the illustration, which realizes a later moment in Warden's interview than in the Leech plate in the 1846 single-volume edition:

There was something naturally graceful and pleasant in the very carelessness of his air. It seemed to suggest, of his comely face and well-knit figure, that they might be greatly better if he chose: and that, once roused and made earnest (but he never had been earnest yet), he could be full of fire and purpose. "A dangerous sort of libertine," thought the shrewd lawyer, "to seem to catch the spark he wants, from a young lady's eyes."

"Now, observe, Snitchey," he continued, rising and taking him by the button, "and Craggs," taking him by the button also, and placing one partner on either side of him, so that neither might evade him. "I don't ask you for any advice. You are right to keep quite aloof from all parties in such a matter, which is not one in which grave men like you could interfere, on any side. I am briefly going to review in half-a-dozen words, my position and intention, and then I shall leave it to you to do the best for me, in money matters, that you can: seeing, that, if I run away with the Doctor's beautiful daughter (as I hope to do, and to become another man under her bright influence), it will be, for the moment, more chargeable than running away alone. But I shall soon make all that up in an altered life."

"I think it will be better not to hear this, Mr. Craggs?" said Snitchey, looking at him across the client.

"I think not," said Craggs. — Both listening attentively.

"Well! You needn't hear it," replied their client. "I'll mention it, however. I don't mean to ask the Doctor's consent, because he wouldn't give it me. But I mean to do the Doctor no wrong or harm, because (besides there being nothing serious in such trifles, as he says) I hope to rescue his child, my Marion, from what I see — I know — she dreads, and contemplates with misery: that is, the return of this old lover. If anything in the world is true, it is true that she dreads his return. [emphasis added: "Part the Second," British Household Edition, p. 132; American Household Edition, p. 122]

Neither Barnard's nor E. A. Abbey's illustration of this protestation quite captures thirty-year-old Warden's earnestness, but Barnard has particularized the attorneys, whereas Abbey has made them similar, giving them both wigs and identical heights. However, other than the box with Michael Warden's name on it (upper right), Barnard gives the reader no sense of the office, whereas Abbey defines the office by its books, papers, and furnishings, and establishes the time of day by the candle.

Realists Barnard and Abbey realise Warden's interview with the lawyers, but Leech's original rendition is more engaging: Snitchey and Craggs, "Now, observe, Snitchey.". Compare these to the almost photographic realism of Charles Green's lithograph Not alone; but with a man of thirty . . . who sat in the arm-chair (1912).

As Cohen has remarked, "the 1846 Christmas book, The Battle of Life, contains a minimum of merriment" (146) and its plot is highly improbable. Nevertheless, the original illustrations do enforce a degree of "suspension of disbelief" in terms of the story's events, even as they add depth to the characters. Only at the end of October had Dickens suggested from Switzerland that the illustrations be cast in the fashions of Goldsmith's period, that is the second half of the eighteenth century, undoubtedly causing the team of artists to rethink their conceptions of the characters. With only a month before publication remaining, Dickens's agent, John Forster, sent the thirteen illustrations by the four artists to Lausanne for Dickens's approval. When he reviewed Leech's three illustrations, he disapproved of Leech's portrayal of Clemency Newcome in The Parting Breakfast, for Leech, with a cartoonist's bent for whimsy, had emphasized the servant's awkwardness rather than her attractiveness. However, Dickens was much more concerned with the inappropriateness of The Night of the Return because it implies that Marion has indeed eloped with Michael Warden, for the young man had stated this very intention in his earlier interview with his lawyers. Consequently, of Leech's three wood engravings the only one of which Dickens really approved was Snitchey and Craggs, which brilliantly integrates text and image, and combines a realistic interior with a visual symbol: a cornucopia surmounted by a stack of bills, its mouth stopped by a large padlock.

In contrast to the despondent Michael Warden (left, his tricorn hat thrown on the floor) and below a padlocked box bearing the letter "W" in John Leech's illustration, the Wardens of Abbey's and Barnard's illustrations seem much more animated. All three illustrations show a fashionably dressed young man of perhaps thirty, his youth and vigour emphasized by the older men who frame him. Whereas Snitchey and Craggs seem to be in doubt, their expressions glum and their gazes downward, Warden's stance and expression suggestive that he is more optimistic and certain of his course of action — which at this point involves eloping with Marion Jedder to save her from an unhappy marriage to Alfred Heathfield. Barnard depicts his Michael Warden as dressed to travel, with a heavy topcoat and riding boots, whereas Abbey's youth wears an embroidered silk vest and walking shoes. The Household Edition illustrators have chosen a moment with considerably more narrative interest than Leech's scene, but they have not made as much of it, perhaps because their realism prevents them from using the kinds of visual symbols that were Leech's stock and trade.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Cook, James. Bibliography of the Writings of Dickens. London: Frank Kerslake, 1879. As given in Publishers' Circular The English Catalogue of Books.

Dickens, Charles. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. Engraved by J. Thompson, Dalziel, T. Williams, and Green. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846 [December 1845].

Dickens, Charles. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Christmas Stories. Illustrated E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. 17 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876. Vol. III. Pp. 111-140.

Dickens, Charles. The Battle of ife: A Love Story. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878. Vol. XVII. Pp. 118-156.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book, 1912.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Parker, David. "Christmas Books and Stories, 1844 to 1854." Christmas and Charles Dickens. New York: AMS Press, 2005. Pp. 221-282.

Patten, Robert L. Chapter 9, "Battling for his Life." Dickens, Death, and Christmas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023. 200-233. [Review]

Slater, Michael. "Introduction to The Battle of Life." Dickens's Christmas Books. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. Vol. 2: 123-126.

Slater, Michael. "Notes to The Battle of Life." Dickens's Christmas Books. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. Vol. 2: 364-365.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

created 14 August 2012

Last modified 9 June 2024