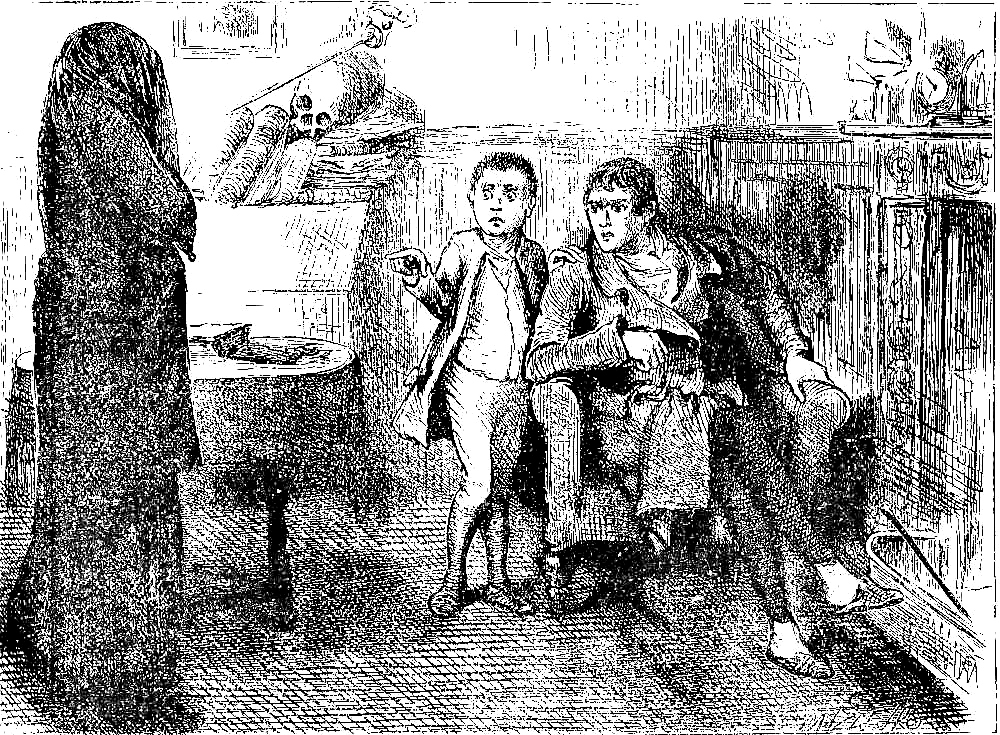

The Black Veil. (wood-engraving). 1876. 9.4 cm high x 13.8 cm wide, framed. — Fred Barnard's innovative response to the kind of short story he would have read in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, the "Tale of Terror" that Dickens composed specifically for the 1836 two-volume Macrone anthology, but which George Cruikshank elected to illustrate in neither the 1836 nor the 1839 editions. Although he utilizes the story for two engaging illustrations, Fred Barnard does not explore the psychological ramifications of the quasi-supernatural account, but is clearly intrigued by its ability to arouse suspense through a gradual darkening of the mysterious atmosphere, as he composed two wood-engravings for it, the first showing the uncanny visitor to the young doctor's surgery in Walworth, and the second (one of only two full-page plates in the 1876 volume) depicting the physician's discovery of the corpse of the son of the deranged woman who has somehow hoped him capable of raising the dead.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

There was a hand upon his shoulder, but it was neither soft nor tiny; its owner being a corpulent round-headed boy, who, in consideration of the sum of one shilling per week and his food, was let out by the parish to carry medicine and messages. As there was no demand for the medicine, however, and no necessity for the messages, he usually occupied his unemployed hours — averaging fourteen a day — in abstracting peppermint drops, taking animal nourishment, and going to sleep.

"A lady, sir — a lady!" whispered the boy, rousing his master with a shake.

"What lady?" cried our friend, starting up, not quite certain that his dream was an illusion, and half expecting that it might be Rose herself. — "What lady? Where?"

"There, sir!" replied the boy, pointing to the glass door leading into the surgery, with an expression of alarm which the very unusual apparition of a customer might have tended to excite.

The surgeon looked towards the door, and started himself, for an instant, on beholding the appearance of his unlooked-for visitor.

It was a singularly tall woman, dressed in deep mourning, and standing so close to the door that her face almost touched the glass. The upper part of her figure was carefully muffled in a black shawl, as if for the purpose of concealment; and her face was shrouded by a thick black veil. She stood perfectly erect, her figure was drawn up to its full height, and though the surgeon felt that the eyes beneath the veil were fixed on him, she stood perfectly motionless, and evinced, by no gesture whatever, the slightest consciousness of his having turned towards her.

"Do you wish to consult me?" he inquired, with some hesitation, holding open the door. It opened inwards, and therefore the action did not alter the position of the figure, which still remained motionless on the same spot.

She slightly inclined her head, in token of acquiescence.

"Pray walk in," said the surgeon.

The figure moved a step forward; and then, turning its head in the direction of the boy — to his infinite horror — appeared to hesitate. ["Tales," Chapter 3, "The Black Veil," pp. 177-78]

Commentary

To fill up the first two volumes of Sketches by Boz Dickens proposed to Macrone that they use several pieces heretofore unpublished out some nine or ten pieces he had already written. In fact, so good were three of these pieces that Dickens and Macrone omitted eight of the sketches published before 1 November 1835 in order to accommodate "The Great Winglebury Duel," which Dickens had written with the Monthly Magazine in mind, and the two darker pieces written specifically for Macrone, the sketch "A Visit to Newgate" and the short story "The Black Veil." The latter is a landmark in Dickens's short fiction, as Peter Ackroyd remarks:

— the saga of a hanged man and his mother — occurred to him [after his 5 November 1835 visit to Newgate Prison], and he set to work on what is really his first proper story; it is no longer a sketch or a scene or a farcical interlude but a finished narrative. Thus we see, in miniature, the formation of the artist, reacting to the events of the life around him, using them and being used in turn. [170]

The Barnard illustration offers no immediate comment upon the nature of the mysterious visitor, whose face is not merely shrouded, but turned away from the reader. We must judge the artist's rendering of her initially by examining the attitude of the surgeon and the boy, and then check their reactions against what the text tells us.

"The Black Veil" deals directly with the idea of insanity. As indicated by the title, reminiscent of the famous black veil in Ann Radcliffe's The Mysteries of Udolpho, this story is clearly linked with the line of Gothic terror, although, as Harvey Peter Sucksmith has observed, Dickens seems more immediately influenced in this piece by the tales of terror published in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine in the 1820s and 1830s, which evoked a sense of fear through specific, realistic details in contrast to the more vaguely suggested fears aroused by earlier, traditional Gothic works like those of Mrs. Radcliffe. More precisely, as Sucksmith has noted, sections of "The Black Veil" are strikingly similar to parts of Samuel Warren's Passages from the Diary of a Late Physician, published in instalments in Blackwood's between 1830 and 1837. [Deborah A. Thomas, "Imaginative Overindulgence," p. 15-16]

Although Cruikshank has not attempted to illustrate this story, probably because it depends so much on an appreciation of the psychological — on the emotional and mental states of the young physician and the anguished mother — rather than on the mere externals with which Cruikshank as a caricaturist felt so comfortable, Fred Barnard has realised in the first illustration two key moments at the very beginning of the story. The first, depicted on the same page as the text it describes, fuses two distinct moments: the first is the boy's pointing towards the enigmatic stranger as she appears at the door (the subject of the boy's excited curiosity); and the second, when, once the doctor has ushered her in, she stands in the surgery, evoking a sense of wonder and mystery in both the young doctor, the messenger-boy, and the reader.

Harry Furniss, benefitting from recent developments in the depiction of psychological states at the end of the century, actually suggests the young doctor's struggling with insomnia as thinks about proposing to Rose, a young woman at home, and bringing her to set up housekeeping in this remote, poverty-stricken hamlet. In the Furniss treatment of this same scene, The Black Veil, the doctor is still dreaming of Rose (centre) as the boy tries to nudge him awake, and the ominous outline of the veiled mother stands at the surgery door (right rear), waiting to be admitted. Barnard's fusion of the two moments is less psychological and more melodramatic. Although Deborah A. Thomas contends that Dickens's primary interest in the story is not the development of suspense so much as the "careful cultivation of the motif of the 'disturbed imagination'" (17) of both the doctor and his mysterious client, Barnard dwells upon the enigmatic appearance of the woman at her initial interview with the doctor and the realistic rather than psychological resolution of her peculiar request when the physician discovers the rope marks on the neck of the corpse. The Barnard illustration does not attempt even to suggest the mother's face, but focuses on the intense gaze of the doctor and the slightly frightened look on the face of the boy, immediately beside the doctor's. Generating suspense is a fourth head in the picture, the skull positioned immediately above three medical books and some notes, nearly on a level with the veiled head, which will in time become the subject of these personal records of peculiar patients. In Barnard's second illustration is a Rodinesque moment not easily forgotten either by the surgeon or the reader:

Viewed in the context of Dickens's other tales, however, the striking feature of "The Black Veil" is not its plot but the stress that it places on the subject of mental aberration. At the end of the story, overwhelmed by grief, the hanged man's mother collapses into madness. — Deborah A. Thomas, "Imaginative Overindulgence," p. 16.

Relevant Illustrations of Other Crime Sketches in the Original Edition

Left: George Cruikshank's caricatural rendering of the apprehension of a petty criminal at Covent Garden, A Pickpocket in Custody. Centre: A physical altercation about to break out in one of the meanest of London's neighbourhoods, Seven Dials. Right: Cruikshank's depiction of the house of detention for debtors, The Lock-up house. Significantly, Cruikshank did not illustrate the companion sketch about crime and criminality, "A Visit to Newgate." [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

The Relevant Illustration from The Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Above: Harry Furniss's psychologically-oriented lithograph of the opening scene of The Black Veil (1910). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicholas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens: Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z. The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. "Tales," Chapter 6, "The Black Veil," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 279-88.

Dickens, Charles. "Tales," Chapter 6, "The Black Veil," Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor & Fields edition]. Pp. 431-37.

Dickens, Charles. "Tales," Chapter 6, "The Black Veil," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Pp. 176-82.

Dickens, Charles. "Tales," Chapter 6, "The Black Veil," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 1. Pp. 358-69.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Chapter 3, "Sketches by Boz." Dickens Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011. Pp. 12-15.

Schlicke, Paul. "Sketches by Boz." Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999. Pp. 530-535.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and the Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Last modified 23 May 2017