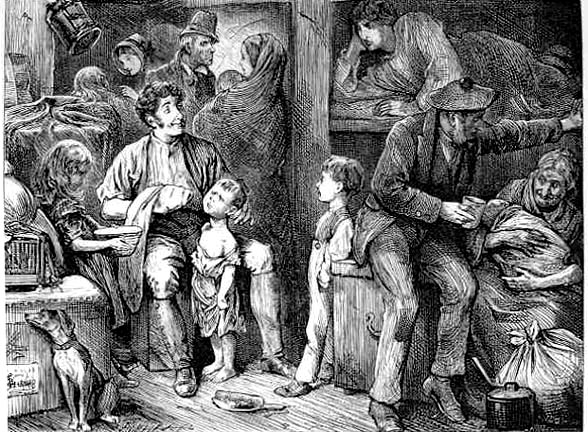

On board the "Screw." (1872). — Fred Barnard's twentieth illustration for Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit (Chapter XV), whole page, vertically mounted (head in), facing page 128. Barnard may well have had such emigrant illustrations as The Emigrants in mind when highlighting the social utility of Mark Tapley's jolliness in steerage, where the affable Cockney assists the adult passengers with their children.] 13.3 cm x 17.5 cm, or 5 ¼ high by 6 ⅞ inches, framed. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Realised in "Steerage"

Mark was so far right that unquestionably any man who retained his cheerfulness among the steerage accommodations of that noble and fast-sailing line-of-packet ship, "The Screw," was solely indebted to his own resources, and shipped his good humour, like his provisions, without any contribution or assistance from the owners. A dark, low, stifling cabin, surrounded by berths all filled to overflowing with men, women, and children, in various stages of sickness and misery, is not the liveliest place of assembly at any time; but when it is so crowded (as the steerage cabin of "The Screw" was, every passage out), that mattresses and beds are heaped upon the floor, to the extinction of everything like comfort, cleanliness, and decency, it is liable to operate not only as a pretty strong banner against amiability of temper, but as a positive encourager of selfish and rough humours. Mark felt this, as he sat looking about him; and his spirits rose proportionately.

There were English people, Irish people, Welsh people, and Scotch people there; all with their little store of coarse food and shabby clothes; and nearly all with their families of children. There were children of all ages; from the baby at the breast, to the slattern-girl who was as much a grown woman as her mother. Every kind of domestic suffering that is bred in poverty, illness, banishment, sorrow, and long travel in bad weather, was crammed into the little space; and yet was there infinitely less of complaint and querulousness, and infinitely more of mutual assistance and general kindness to be found in that unwholesome ark, than in many brilliant ballrooms.

Mark looked about him wistfully, and his face brightened as he looked. Here an old grandmother was crooning over a sick child, and rocking it to and fro, in arms hardly more wasted than its own young limbs; here a poor woman with an infant in her lap, mended another little creature’s clothes, and quieted another who was creeping up about her from their scanty bed upon the floor. Here were old men awkwardly engaged in little household offices, wherein they would have been ridiculous but for their good-will and kind purpose; and here were swarthy fellows — giants in their way — doing such little acts of tenderness for those about them, as might have belonged to gentlest-hearted dwarfs. The very idiot in the corner who sat mowing there, all day, had his faculty of imitation roused by what he saw about him; and snapped his fingers to amuse a crying child. [Chapter XV, "The Burden Whereof is, Hail, Columbia!"]

Commentary: Mark's Jolly Voyage

Perhaps because the Scots hat, the Tam o' Shanter, is so easily drawn and is so instantly recognizable, Barnard uses it here as a visual metaphor for British immigrants to America. Immediately behind Mark stands an immigrant wearing a distinctly Irish hat. In the midst of the close-packed quarters of the lowest class aboard The Screw, the Steerage, Mark remains remarkably cheerful, perhaps because he can be of such service to the multiple young families emigrating to the United States aboard the ship that has sailed from the port of Liverpool. He is of particular service and looks especially jolly when assisting an immigrant woman (in the bunk, upper left) who is travelling to New York to join her husband; the three children keep Mark busy. Young Martin is miffed that his valet is not paying him more attention. The proud youth spends the entire voyage in the common cabin because he is too embarrassed to be seen on deck as a mere "steerage" passenger. His experience, therefore, is nothing like that of first-class travellers Charles and Catherine Dickens in 1842 aboard The R. M. S. Britannia, the Cunard Line's first paddle-steamer (a stormy passage, January 2nd through 22nd) bound for Boston via Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Dickens, Charles. The Dickens Souvenir Book. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871-1880. The copy of The Dickens Souvenir Book from which these pictures were scanned is in the collection of the Main Library of The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B. C.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman and Hall, 1844.

_____. Martin Chuzzlewit. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1863. Vol. 2 of 4.

_____. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872. Vol. 2.

_____. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated Sterling Edition. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne and Frederick Barnard. Boston: Dana Estes, n. d. [1890s]

_____. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 7.

Steig, Michael. "From Caricature to Progress: Master Humphrey's Clock and Martin Chuzzlewit." Ch. 3, Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978. Pp. 51-85. [See e-text in Victorian Web.]

Steig, Michael. "Martin Chuzzlewit's Progress by Dickens and Phiz." Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972): 119-149.

Last modified 22 July 2016

Last updated 19 November 2024