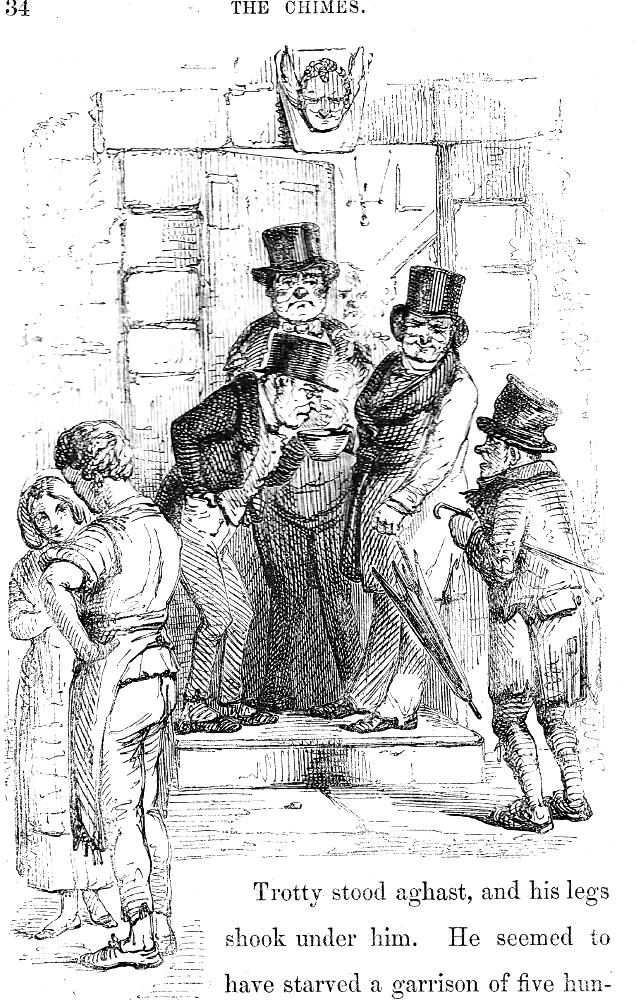

"What's the matter? What's the matter?" said the gentleman for whom the door was opened." by E. A. Abbey. American Household Edition (1876), first illustration for The Chimes: A Goblin Story, "First Quarter," in Dickens's Christmas Stories, 10 x 13.4 framed, p. 48. [Click on the image to enlarge it.] See commentary below.

In illustrating this cautionary tale for the Hungry Forties, John Leech and his team of artists (including Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, and Clarkson Stanfield) had begun with the supernatural agents of Toby Veck's social reintegration, depicting cavorting goblins in "The Spirits of the Bells" and "The Tower of the Chimes" in advance of beginning the text with an ornate capital "T" containing a square church tower and, in the filigree work below, Trotty and Meg sitting on the church steps ("The Dinner on the Steps"). Abbey begins instead with a realistic realisation of the story's class divisions. The diminutive Trotty has his finger to his lip, as if uncertain about what to say as his superiors, at least a head taller and much broader than the little ticket-porter, filling the centre and right register in top-hats and topcoats, analyse his lunch as a model of political economy.

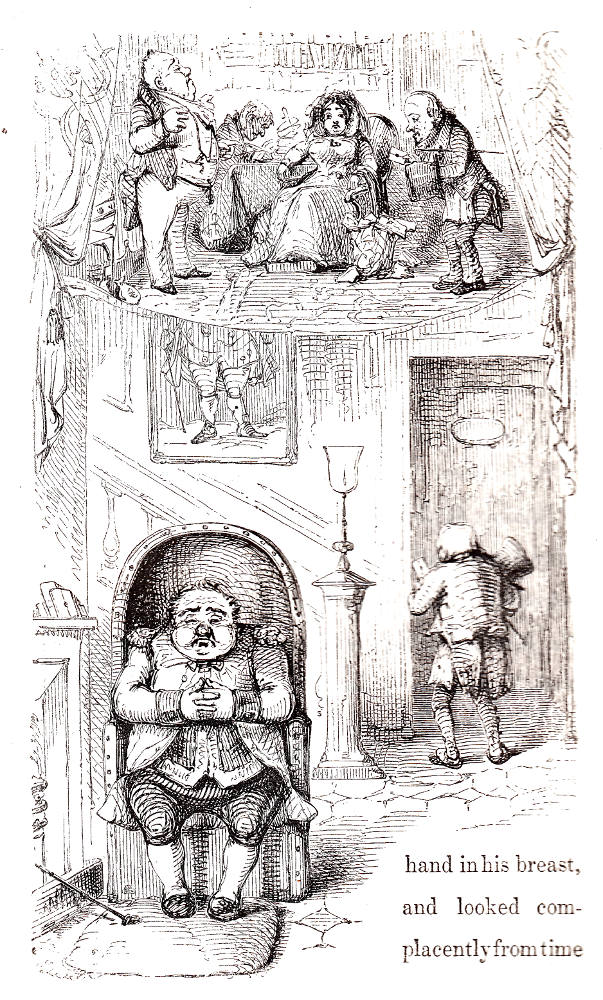

Various interpretations of Trotty's dinner al fresco. Left: Richard Doyle's illustration of "The Dinner on the Steps". Centre: John Leech's illustration of the Trotty's being upbraided for eating tripe: "Alderman Cute and His Friends" (1844). Right: Fred Barnard's illustration of Trotty Veck's earlier savouring the ordor of hot tripe in Meggy's basket on the steps of St. Dunstan's: "'No,' said Toby after another sniff. 'It's — It's mellower than Polonies'" (1878).

Passage illustrated by E. A. Abbey:

"What's the matter, what's the matter!' said the gentleman for whom the door was opened; coming out of the house at that kind of light-heavy pace — that peculiar compromise between a walk and a jog-trot — with which a gentleman upon the smooth down-hill of life, wearing creaking boots, a watch-chain, and clean linen, may come out of his house: not only without any abatement of his dignity, but with an expression of having important and wealthy engagements elsewhere. "What's the matter! What's the matter!"

"You're always a-being begged, and prayed, upon your bended knees you are," said the footman with great emphasis to Trotty Veck, "to let our door-steps be. Why don't you let 'em be? CAN'T you let 'em be?"

"There! That'll do, that'll do!" said the gentleman. "Halloa there! Porter!" beckoning with his head to Trotty Veck. 'Come here. What's that? Your dinner?"

"Yes, sir," said Trotty, leaving it behind him in a corner.

"Don't leave it there," exclaimed the gentleman. "Bring it here, bring it here. So! This is your dinner, is it?"

"Yes, sir," repeated Trotty, looking with a fixed eye and a watery mouth, at the piece of tripe he had reserved for a last delicious tit-bit; which the gentleman was now turning over and over on the end of the fork.

Two other gentlemen had come out with him. One was a low-spirited gentleman of middle age, of a meagre habit, and a disconsolate face; who kept his hands continually in the pockets of his scanty pepper-and-salt trousers, very large and dog's-eared from that custom; and was not particularly well brushed or washed. The other, a full-sized, sleek, well-conditioned gentleman, in a blue coat with bright buttons, and a white cravat. This gentleman had a very red face, as if an undue proportion of the blood in his body were squeezed up into his head; which perhaps accounted for his having also the appearance of being rather cold about the heart.

He who had Toby's meat upon the fork, called to the first one by the name of Filer; and they both drew near together. Mr. Filer being exceedingly short-sighted, was obliged to go so close to the remnant of Toby's dinner before he could make out what it was, that Toby's heart leaped up into his mouth. But Mr. Filer didn't eat it.

"This is a description of animal food, Alderman," said Filer, making little punches in it with a pencil-case, 'commonly known to the labouring population of this country, by the name of tripe." ["First Quarter," 48-49]

Abbey's illustration of this scene compared to those by Leech, Doyle, and Barnard

In the original 1844 sequence of thirteen illustrations by four artists working in loose collaboration and directed by Dickens himself, John Leech provided five pictures, as in A Christmas Carol (1843). His first and second woodcuts respectively depict Trotty Veck running through the streets of London, and Alderman Cute and his hangers-on confronting Trotty about the economic downside of the of poor man's eating tripe ("Alderman Cute and his Friends"), an illustration which E. A. Abbey reinterpreted in a more realistic vein in the American Household Edition. Fred Barnard, having less than half-a-dozen plates to commit to this piece of social realism, elected to show Trotty's interaction with Sir Joseph Bowley and his wife rather in the library at his townhouse than with Alderman Cute and his hangers-on in front of the Church of St. Dunstan's-in-the-East (originally built about 1100, but replaced in 1818, and therefore something of an anachronism in this story) on New Year's Eve, 1843.

Barnard's illustration depicting only Trotty and his daughter in closeup occupies almost three-quarters of a page, and at 13.7 cm long by 10.8 cm wide certainly establishes the father-and-daughter relationship as the principal relationship of the novella. Abbey, in contrast, relegates Meggy and her fiance Richard to the background, and gives them mere observer status. Moreover, whereas Leech depicts them as young lovers, thoroughly engrossed in each other and blissfully unaware of the scene unfolding behind them, Abbey moves the couple into the background and does not particularise Richard as a blacksmith, giving him a working man's cloth cap and having him protectively holding Meg's hand (but in no other way signalling the nature of their relationship).

As in Barnard's initial plate, Abbey provides a sketchy backdrop, old Saint Dunstan's Church, by providing area railings (left) and the columns of the church porch (centre, rear). Richard Doyle's representation of the church's Gothic lantern-tower in "The Dinner on the Steps" and Stanfield's "The Old Church", emphasizing the Gothic lantern tower of old Saint Dunstan's, is far more atmospheric, but reduces considerably the importance of the figures below by subordinating them to the architectural elements in both 1844 engravings. E. A. Abbey merely suggests the exterior setting, concentrating instead on the figures in the foreground: the off-centre, diminutive figure of the ticket-porter, and the tail- and top-coated gentlemen who are critically examining his lunch as if it were some sort of exotic plant specimen or ancient artifact. Neither Household Edition illustration suggests the seasonal setting of cold winds, ice, and snow since there is no slush on the pavement and no icicles, although Richard (left rear) and the gentlemen are wearing gloves, and (unlike Leech's young blacksmith) is not in his shirtsleeves.

There is much in Abbey's reinterpretation of Leech's 1844 "Alderman Cute and Friends" which suggests the new Sixties style of Luke Fildes' illustrations for Dickens's last serialised novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood — in particular, compare Abbey's disposition and modelling of the figures on a narrow forestage to the same features in "Durdles Cautions Mr. Sapsea Against Boasting", an illustration of comparable size and orientation in which a man of the labouring classes (as identified by his clothing) mingles with his fashionably clad social superiors with an urban backdrop sketched in behind the figures.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting, color correction, and linking by George P. Landow. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

References

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

---. Christmas Stories. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

---. The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Il. Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1880.

Parker, David. Christmas and Charles Dickens. New York: AMS Press, 2005.

Last modified 3 December 2012