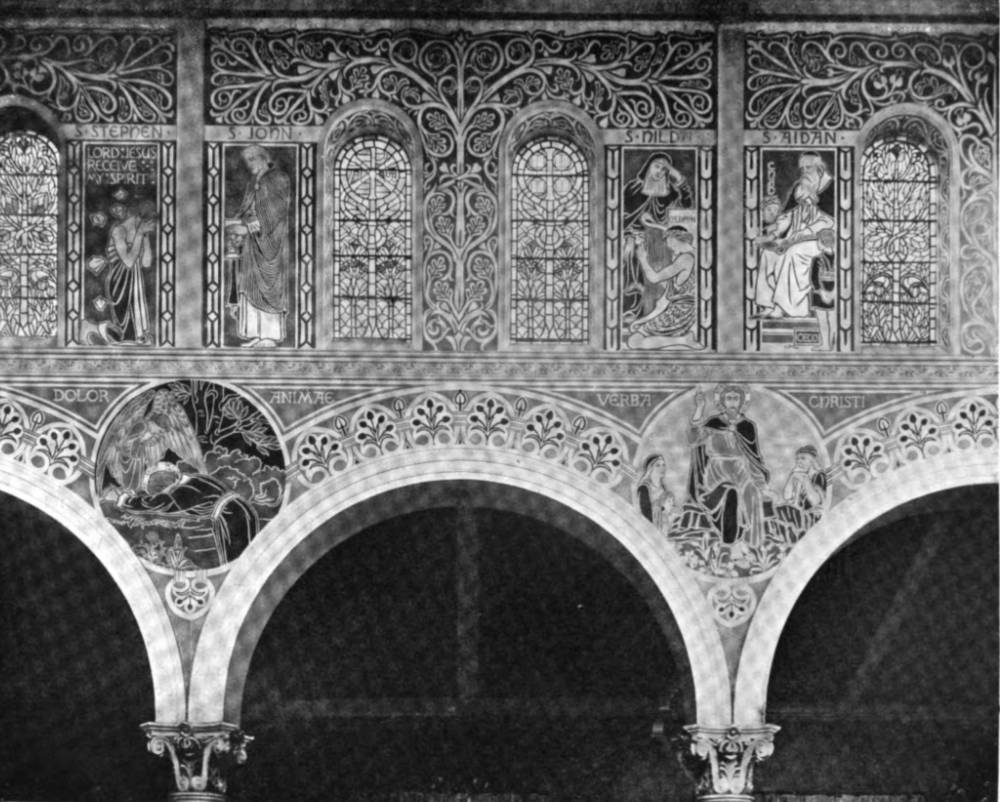

Sgraffito decoration in progress at Lady Chapel, St. Agatha’s, Landport. J. Henry Ball, Architect.

IT is depressing to begin an article with the assurance that it is going to be dull, but such is my case.

The nature of technical matters is to be dull when they are reduced to writing. If you do this, that will happen — If you don't do this, the other will happen — You must be sure to do so and so, or this and that will be the result — Beware — Be bold — Be not too bold — and so on and so on; such is the nature of writing on technical matters, and of the studious attempt to recapitulate in print proceedings which are only capable of complete explanation in practice, in the handling of material, and in the exhilarating struggle to produce a result within the limits of your technique.

Moreover, such methodical treatise cannot be lightened nowadays by those airy excursions into antiquity, or into mythic science, which beguiled our forefathers. They embroidered their subject with a bird's-eye view of Creation, with a story on hearsay from Plutarch, or with travellers' tales of the marvellous barnacle tree, but we are supposed to be historical, critical, comparative, analytical — in short, to be omniscient; and so it comes to pass that otherwise pleasant people produce ex haustive papers and become Eminent Authorities. From this latter fate, at least, I am secure. My article is practical and technical — the experiences of a craftsman in sgraffito; and though at best I can only anticipate being "dull in a new way " to the general reader, yet I hope that this article may be of service to the few workers who have any concern with monumental de coration, and may lead to permanent results on now silent walls.

And so to work without further apology. First — what is sgraffito? The Italian words graffiato, sgraffiato, or sgraffito, mean "scratched," and scratched work is the rudest form of graphic expression and surface decoration used by man. The term sgraffito is, however, specially used to denote decoration scratched or incised upon plaster or potter's clay while still soft, and for beauty of effect depends either solely upon lines thus incised accord ing to design, with the resulting contrast of surfaces, or partly upon such lines and contrast and partly upon an under-coat of colour revealed by the incisions; while again, the means at disposal may be increased by vary ing the colours of the under-coat so as further to express the design.

In this article I am only dealing with sgraffito as applied to inside wall decoration. Now the walls which you may be called on to decorate will be either bare or plastered. If bare, you will be spared some trouble and a great deal of dust; for all you will have to do before making a start will be to rake out thoroughly the mortar joints of the brick or stone wall, brush out thoroughly all sandy dust from these raked- out joints, and peck the surface of brick or stone where needed so as to give a good key for the coarse coat.

If, however, the walls are plastered, you must begin by hacking off all the existing plaster, raking out the joints, brushing and pecking the wall as before directed, thus preparing it to receive your first "rendering" coarse coat of Portland and sand. Be sure that you use Portland cement of the best quality. I always use White's. The sand should be well washed, sharp grit, the best obtainable. Why? because inferior sand may have clay nodules or dirt in it, and when this is the case you will be disagreeably informed of the fact by the finishing coat of your work "blowing," that is to say, being defaced by little pockmarks, small circles of plaster being raised on, and then detached from, the finished surface wherever a soft nodule of clay is con cealed behind in the coarse coat.

The gauge of the first or rendering coat of coarse stuff may be two or three of clean sharp sand to one of Portland, and care should be taken that the two ingredients are thoroughly well mixed, otherwise the permanence of your work will be endangered. [21/22]

Now give the wall as much water as it will drink, and the rendering, or flanking in, as it is sometimes called, can begin.

When the wall has been duly rendered, the surface of the coarse coat should be roughened, either by scoring it, or by stubbing it with a stiff broom, the purpose in either case being to obtain a rough surface of ins and outs so as to make a good key for the succeeding coats of plaster.

The use of this coarse coat is twofold: it keeps back damp which in the nature of things occurs on the outer side of the wall, and promotes an even suction for the succeeding coats of plaster — an even suction being most necessary, otherwise one part of your day's ground would immediately "go in," i.e., the water would be quickly drawn from it by a thirsty part of the wall, while another part, where the suction was slow, would keep soft, the upshot being firecracks where the suction was fierce, delay where the suction was slow, bad work and words.

In about two days' time the coarse coat will be sufficiently set for you to begin marking in your design on the rough grey wall. I will suppose figure designs in various colours. These, drawn on stout cartoon paper, must have been previously pricked in outline. This pricking may be well done with a darning needle fixed in a penholder bound round with string— like a bat handle — for secure holding, while the cartoon should be placed on a thick blanket so as to admit of the needle piercing the paper; when the pricking is done the paper burr at the back, round the prick-holes, should be removed by scouring with sandpaper, otherwise they will be closed up by the ragged edges of the pricked paper, and your pounce impression will be imperfect.

Now get up your cartoon in its proper place on the wall, and pounce it on. For this purpose your pounce may be dry Parian wrapped in a muslin bag. Mark pencil rings on the cartoon round the nail holes on which your cartoon is supported; remove the cartoon; replace the nails in the same holes in the wall, and paint white rings round them. These are the register holes of your cartoon, and accordingly of your colour spaces; they must be carefully kept, otherwise you will have much unnecessary trouble. In the case of large cartoons you will find it convenient to glue luggage-label ends, on which are ringed string holes, to the two top corners of the cartoon. This will prevent the paper being torn away by the weight of the cartoon, and the register consequently being dropped.

Left: Wall space “marked in” (Brereton, Rugely, Staffs). Right: The same wall space, showing final result in Sgraffito. Designed and executed by Heywood Sumner.

Now you will have a clear impression of your design in small white dots on the grey coarse coat, and, if you have designed your cartoon with due understanding of the capabilities and limitations of your method, you should soon accomplish the work of marking-in the different spaces of colour with white paint and a hog-hair brush. To this question of design, its capabilities and limitations in sgraffito, I shall return later on; we are now concerned entirely with method.

When you have done the marking-in, the wall will be divided up into a sort of map of white-lined spaces, as shown in the illustration, and each space should be marked with a letter showing your plasterer what colour to lay in the space, this being the end in view of the marking-in. Now you are ready to begin the actual execution of the sgraffito. Up to this point your plasterer has been doing his work, rendering the walls, and you have been doing yours, marking in your designs; now, however, you will work together in much closer union, and must plan each day's work ahead for the next week, or more, so that the coloured plaster for next day's work may be got on to-day, and so on from day to day. Why? Because sgraffito work is "fresco" in the true meaning of the word: it must be done— fresh; the process being that one day you lay a ground of coloured plaster, the next day you cover this with a thin layer of white plaster, and then cut your design out of this thin white layer, thereby revealing the coloured ground below.

Well, when you have talked over your wall and all its marking-in with your plasterer, and explained to him, if he is new to your methods of work, the colour mean ings of the letters in the spaces, e.g., R — red, B— blue, G — green, C — crimson, etc., then you should give him a written list of the different gauges of colour, to be fixed up in easy view for reference as he gauges up the colours on his colour banker. If you are using several colours, you will find it convenient to fix up divisions like stalls on a long board so that each colour may have its own place, and you also should provide yourself with several hawks, or mortar boards, so that each colour [22/23] may have its own hawk. The following is a gauging list of colours which may be found useful, the colour being in all cases Mander's powder distemper colour, and the cement with which it is mixed being fine Parian. I have noted anything special in their respective behaviour on the wall.

- Turkey red. 1 of colour, 3 of Parian.

- Bright red. 14 Turkey red, 1 fast crimson, 8 of Parian, will set quicker than No. 1, and harder.

- Indian red. 1 of colour, 3 of Parian (slow in setting and some times salt).

- Red oxide. 1 of colour, 3 of Parian (a brownish red, slow in setting).

- Fast crimson. 1 of colour, 3 of Parian a very fine strong colour, needs a good deal of knocking up to mix it properly).

- Brown. 1 of raw umber, 3 of Parian (slow in setting).

- Red brown. 1 of raw umber, ½ golden ochre, ½ fast crimson, 6 of Parian.

- Purple. 1 of fast crimson, 1 of ultramarine blue D, 6 of Parian (sets quickly and some times salts. Purple can be modified by adding 1 of French ochre to the above, and 3 of Parian).

- Bright blue. 2½ ultramarine blue D, ½ French ochre, 9 of Parian (sets quickly and very hard, and frequently salts. The French ochre modifies the fierceness of tone of this blue, and the above gauge may need further modification under cer tain circumstances of lighting and position).

- Dark blue. 2½ lime blue, ½ French ochre (sets quickly and sometimes salts).

- Pale blue. 1½ ultramarine blue D, 1½ lime green. 9 of Parian (sometimes salts).

- Green. 1½ ultramarine blue D, 1½ French ochre, 4 lime green, 9 of Parian (sets rather quick and frequently salts). Dark green, ½ lime blue, 1½ golden ochre, 9 Parian; or 1½ lime blue, 1 umber, 1 French ochre, 9 Parian. Yellow. 1 golden ochre, 3 Parian.

- Light yellow. 1 French ochre, 3 Parian.

- Brown yellow. 3 French ochre, ½umber, ½ crimson, 10½ Parian.

- Black. 1 blue-black or man ganese, 3 Parian.

None of the colours mentioned are expensive except fast crimson, 2s. 6d. per lb., ultramarine blue D, is. 6d. per lb., and lime green, is. per lb.

Of course, by reducing the amount of colour, and thereby increasing the amount of Parian, you can get lighter shades of any of the above colours; but do not forget that an increase of Parian means quicker setting, and you must allow for this in the time of getting on your colour-coat beforehand; otherwise, when you cut the final coat you will find your colour-coat cleans up very hard, smooth, shiny, and unduly grey.

Blue sets harder and quicker than any of the other colours, and it frequently salts in the process of drying out. That is to say, a white efflorescence of saltpetre appears on the colour surface. Leave this alone till it is quite dry, and then brush it off with a stiff dry brush, and rub over the colour with a damp rag, after which the original colour of the blue, green, or purple will be completely and permanently restored. The colours

which will be laid the first thing next morning.

>Sketch Design by Heywood Sumner, for Sgraffito Decoration executed in the centre apse, St. Agatha's, Landport, Portsmouth. J. Henry Ball, Architect.

For the final coat I use fine Parian, which sets as white as milk and cuts like cream cheese, with no imperfections of any kind; only — like Mr. Toot's tailor— it is expensive. If you should find that it sets too quick, air-slake it, i.e., spread out some cement on the top stage of your scaffold, or in some place where no dust or grit will fall on it, and leave it exposed for twelve or twenty- four hours before using. If you want a creamy rather than a milk-white ground, soak half a gallipotful of golden ochre in a bucket of water, stir well, then strain, and use this ochre water for gauging up your Parian final coat, taking care that it is well stirred before use.

If you and your plasterer are strangers, you should be up betimes to see after the ochre water, the laying of the final ground to the right thickness (one-sixteenth, one-eighth, to one-fourth, according to the distance of the work from the floor), the keeping of the register nails, etc.; but if you are accustomed to work together, and mutually know where each comes in, you ought not really to be wanted early, while you will be wanted late; in which case make your arrangements for begin ning on the fresh-laid ground between eight and nine o'clock. The ground should be trowelled-up quite firm to the touch, and without any damp shine on it before you begin cutting it. When ready, get up your cartoon in its right place as indicated by the register nails; mind the back of your cartoon is quite clean; pounce your design on the newly-laid white ground; use Portland cement for your pounce, the grey powder of which will give a clear impression on your ground. [24/25]

Sgraffito Decoration, All Saints, Ennismore Gardens, London — part of North Wall. Designed and executed by Heywood Sumner.

Now for the execution of the "scratching," or really cutting, for nothing gives such clean, quick results as a knife blade fixed in a tool handle; with this tool you may learn to work with such rapidity that it will take two if not three assistants to follow you cleaning up the spaces of colour and the lines which you have cut; and you will soon find that you must be ambidextrous in order to overcome the obstacles of inconveniently placed scaffold-poles and stages. For the first hour or two you should cut in outline all the large spaces of colour, backgrounds, long lines, etc., because the final coat when first laid on will scale off quite easily from the colour coat; gradually, however, the final coat will begin to set and to adhere to the colour coat, and as the day goes on your rate of progress will get slower and slower. At first the final coat cuts like cream cheese under your knife, then "short," i.e. crumbly, then tough, then hard, and finally like stone. It is better to leave all fine work, such as heads, hands, and feet, to the tough stage; and you should use special care in cutting during the "short" stage, otherwise you have to spend valuable time in mending breaks. Note that in cutting you should always slant your knife away from the edge which you mean to leave as a sharp outline, because the act of cutting is apt to shake the key of the final coat; by slanting your knife aright you leave intact the plaster which is to remain, and you disturb the key of the plaster that is to come away, thereby facilitating the work of your assistant who is following you up, removing the spaces of cut-out plaster and cleaning up.

The cleaning up is of great importance, as on this depends the strength and quality of your colour. When the final coat is first cut and removed so as to show a [24/25] space of colour, such space will be greyed by the adhesion of small particles of the final coat. In order to remove this greyness the colour surface should be scraped with a plasterer's small tool, and a good cleaner will get handling as well as colour into the scraped surface by the direction and manner of his scraping.

Sgraffito Decoration, All Saints, Ennismore Gardens, London — part of South Wall. Designed and executed by Heywood Sumner.

I have already mentioned that some colours, when mixed with Parian, set much quicker and harder than others. You should arrange to have these colours laid on the last thing before your plasterer finishes work; and you must never get on more than the next day's colour on the walls, otherwise you will find that when you try to clean up your colour coat it will scrape smooth, grey and shiny, instead of rough and full- coloured, and all your efforts will be unavailing to get up your colour to its proper strength.

The colour coat throughout your work should be followed on within twenty-four hours as the outside limit, and should be scraped immediately after it is cut, and then left alone. You must give all your colour similar conditions in order to obtain a one-stuff quality for the whole of the work.

If you find that you cannot finish the whole of the ground which you have had laid for your day's work, harden your heart, and cut off what you cannot finish; lay fresh colour, and start afresh on a new ground next day. But, notwithstanding, you ought to estimate rightly, and you ought so to arrange that your whole gang are fully employed all day, and the day's work done as planned.

If you wish to finish off your wall decoration with plain spaces in the filling or frieze, above or below your sgraffito decoration, you will find that a pleasant variety to these incised and sunk colour surfaces may be obtained by flush filling in work. In this case }-ou lay your Parian final coat straight on to the coarse coat about 1-inch thick, cut it according to your design (which must be quite simple, ungraphic, and with large interspaces), and when this is set, fill in the interspaces flush with selenitic sand and colour, or with Parian sand and colour, finishing with a floated rough surface to contrast with the trowelled smooth surface of the Parian, and cleaning off any colour stains which may be made on the Parian in the course of floating up the flush, rough-surfaced colour coat.

I now come to the question of design. Simplicity of expression and a rigid selection of your graphic materials are imposed on you by the method. Light on dark; dark on light; colour spaces and colour lines telling against a white ground; white spaces and white lines telling against a colour ground; contrasts of pale against dark colour spaces; juxtapositions of colour [25/26] spaces in harmony, or in opposition, warm or cool, dark or pale in incidence; these are the restrained means at your disposal. You must welcome line as your means of expression, and instead of aiming at an impossible realism, you must try to find the vitally expressive line, the essential character, movement, posture, growth and colour; in short, the graphic generalisation of the natural forms with which your decoration is concerned; and remember that your result will be effected as much by omission as by commission; right leaving out in your design is just as important as right putting in, and interspace forms must be considered as much as silhouette forms.

Sgraffito Decoration in the garden corridor of a private house, Winchester. Designed and executed by Hey wood Sumner.

Moreover, you must design with a clear perception and good-humoured acceptance of the limitations imposed by the building which you are decorating. In all our endeavours many qualities and many differing con siderations go to make up the final result, yet there is always one — First. One thing we must seek first if the other things are to be added to us; and the first thing needful in design for wall decoration is that the decora tion should belong to its place. It should seem to grow out of the wall spaces, and grow in a temper of accept ance and in relation to the scale of the building.

No words of advice can achieve such consummation devoutly to be wished for, but you will be on the road if you begin with knowing your building and wall spaces by heart; brooding over them, dreaming of them, until your decoration takes shape in forms and colours of rhythmic harmony, gradually to be fulfilled in the actual execution of the work. And this is of necessity in sgraffito. You must carry out the work yourself in situ, you must be quick about it, and you must learn to see through scaffold-poles, and putlogs, and stages in the execution of your designs. No easy matter revising your work under these con ditions, or to allow for the different lighting a wall gets when the scaffold is gone. But practice— though it will not make you perfect — will at least give you experience, and diminish the number of your mistakes.

Finally, in your graphic expression you must feel the monumental character of your work— monumental- something which stands, or remains to keep in remem brance what is past. So says the dictionary, and the words have a noble cast about them, raising us up into the realms of

“The antithesis of things that bide,

The cliff, the beach, the rock, the tide—

The lordly things, whose generous feud

Is but a fixed vicissitude."

This is the sphere of monumental decoration: To stand— to remain — to keep in remembrance -something rooted, belonging to its place. Not to be bought here, and sold there, in the eager competition of connoisseur- ship; not to be rushed about the world wherever men may agree to swarm in exhibition, but a thing securely planted in one place, and created with the stable as surance of natural growth.

Every artist who has had the happiness to spend laborious days on wall decoration must have felt an exaltation of soul in his work and in the thought of days to come.

There they stand, the walls that speak: men will come and go; creeds and government will change in their ex pression, their emphasis, and their sway; beliefs will shift; hopes will rise and fall; things will happen very differently from what we may guess; but still the walls will utter their silent visionary message to future genera tions of men as they strive, and achieve, and linger, and pass by. Dimly by night the presences shadow the walls; brightly by day they inhabit their set place. No change nor chance will affect them except the sure age long decay of the nature of things, and except — a great exception— except destruction. Yes, murder and sudden death are fates which again and again have destroyed these things which stand, which remain, which keep in remembrance. Alas! that the graphic stories and insistent presences which inspire and express the ideals of one generation should live to be hated by another. This is Idolatry. That is Heresy. This is detestable. That is ridiculous. They must be hacked off, obliterated, covered with paint, plaster, anything so as to destroy the vision that is inevitable, anything so as to reduce the recording walls to blank silence.

Or again. Think of the glories of glassy colour which have been shivered into ruin; or which, from hasty care and secret burial, have arisen in shattered splendour to attest the fury and the folly which may possess the minds of men. Ah, poor monumental artl so often prone, so often remaining as a castaway landmark in a strange land, while the past which it commemorates is so little remembered, so lightly honoured !

And yet — and yet — although we know all this; although we know the wreck of Time; although now we may sometimes fear whether the world within us has any part with the mechanical world without, and whether our graphic language of ideal symbol can appeal to this matter-of-fact generation; notwithstanding this know ledge, and notwithstanding these blank misgivings, we artists, by our high calling and vocation, are bound to ignore them, and to do our work of hand and soul with the constant belief that it is wanted, that it is what we were made for, and that it wIll remain.

Heywood Sumner

Bibliography

Sumner, Heywood. “Sgraffito as a Method of Wall Decoration

Last modified 5 November 2019